I'm going to blame Eephus for this. We were shooting the virtual breeze (mostly about how challenging it can be to find something in the Archives here) and he thought an updated Blue Jays entry of the Lobby of Numbers made a bit of sense. You know, when times are hard one can always reflect on the Better Times we've had. Or the times that were even harder.

The original Blue Jays entry that opened the Lobby. way back in May 2005 was just a casual one-off piece on uniform numbers, But I was younger then, full of vigour and energy and all that, and started doing sequels. I zipped through most of the AL East in a matter of weeks. And then I started getting carried away. As I do. I got into looking at team histories. I started finding cool pictures. I can't help myself.

So those very first entries, on the AL East teams, seem somewhat skimpy to me now. Especially the Blue Jays entry. And hey... it's been almost twenty years. Things have happened. I can report that many of my original choices for the Blue Jays edition of the Lobby retain their Position of Honour, but we've seen a few deserving fellows from these last two decades, who have been patiently awaiting their own place in these Unhallowed Halls.

So let's get to it.

2. This had long been the number given to mediocre infielders - Fred Manrique, Luis Sojo, Danny Ainge, Dave Berg. Back in 2005, I went with Nelson Liriano, who had a nice season in 1989 as part of a second base platoon. We have better options now. Troy Tulowitzki, his defense especially, was a vital part of those 2015-16 teams. But a) Tulo couldn't stay healthy, and so b) the Blue Jays ended up paying him something like 113 million dollars to play 238 games. I'm not Warren Buffett, but that seems like poor return on investment, and it takes a bit of the shine off. So we're going to go with Aaron Hill here. He was drafted out of LSU with the 13th overall pick in 2003, and played shortstop in the minors. He made it to the majors in 2005, playing mostly third base in place of the often injured Corey Koskie. He got a long look at second base in September when Orlando Hudson was hurt, and he took over at second the following season once Hudson had been traded to Arizona. His offensive production here was unpredictable - as a Jay, he could hit anywhere from .205 to .291, as many as 36 HRs or as few as 6. His glove work never faltered.

3. Jimy Williams took this number out of circulation during his years as a coach and manager. For a long time the most noteworthy playing performance was turned in by Mookie Wilson during the 1989 stretch run. It was just two months, but he was on fire. Now, I think we'll single out Old Sparky. Reed Johnson wore this for his last three Toronto seasons, and the one in the middle (2006) was simply sensational - .319/.390/.479 - from someone who was supposed to be the fourth outfielder, but played far too well to take a backseat to anyone. I'll always remember him for what I thought of as Sparky's Tripod. It was the way he stood in the batter's box with his legs apart, the bat resting against his crotch while he adjusted his batting gloves.

4. George Springer had been making a pretty decent case, but I'm going to hold off. I don't think George is toast just yet, but I am alert to the possibility. For now, we'll stick with Alfredo Griffin. It's been twenty years, and Griffin has lost most oi the places he used to hold among franchise leaders. Except for triples and caught stealing, which totally figures. Alfredo was the most aggressive baserunner I have ever seen. If there was such a category as Insane Basepath Commando Raids - he'd be your man. ( I will always remember him scoring from second base on Sprague's infield ground out against Seattle.) Bill James once suggested that Griffin was the dumbest player in the majors - he showed no growth at all (his best season, by a mile, was his rookie year), he made tons of errors, he had no plate discipline, he was a terrible percentage base stealer. James was mystified by this, as he and everyone in baseball knew that Griffin was universally regarded as one of the brightest people around and nobody's fool - sharp as a tack, and very smart about money. Just not on a baseball diamond.

Incidentally, the historical record says that Griffin played in 982 games as a Blue Jay. This is wrong, and it will forever be wrong. It was 983. One day in 1992, he came off the bench to replace Roberto Alomar at second base for the final inning. I was in the press box scoring the game for STATS, and I duly noted the lineup change. Duane Ward got the final three outs on about eight pitches, none of which were hit anywhere near second base. Half an hour after the game the office was on the phone to me wondering why I was the only person on earth who had Griffin entering the game. Because he did, I said. But the official scorer hadn't noticed. Howie Starkman of Jays PR, who normally announced all these moves to the press box, hadn't noticed. Howie and I actually went and watched the video of that last inning and there was simply no shot of the second baseman. But I promise - there is no way on earth I or anyone else could have looked at Roberto Alomar and thought they were seeing Alfredo Griffin. No way whatsoever. So it definitely happened. But I'm the only who noticed.

5. No disrespect to John Gibbons, but we do have a worthy player here and so this is still going to be Rance Mulliniks. He didn't look like an athlete - he looked like the guy who did your taxes. Played 1,115 games for the Blue Jays (8th all time) and hit 204 doubles (10th all time.) He appeared in 11 seasons, hitting .280/.365/.424 and lasted just long enough to get a ring in 1992 (he was on the active roster for the World Series, but didn't appear in a game.)

6. First Marcus Stroman put in a claim, and now Alek Manoah is doing his best. But while Bobby Cox is in the Hall of Fame mostly for his work in Atlanta, he began to build his legend right here. As everyone knows, Cox was ejected from more games than anyone in MLB history. Why was that? What made him one the game's truly legendary yellers and screamers? Well, Bobby Cox really, really liked winning. And he got very, very upset at anything that interfered with that overriding goal - his own players, the other team, the umpires. When he arrived here in 1982, Cox actually expected his Blue Jays to win, and this - this was simply unprecedented. No one else expected it, no one had even considered the possibility. The thought simply hadn't occurred. It had occurred to Bobby Cox though, and he raised the bar for everyone.

7. Shannon Stewart and Edwin Encarnacion both wore this at the beginning of their Blue Jays careers before finding some other digit they liked better. Tony Batista had two remarkable seasons here. Then Batista had a bad first half in 2001, Gord Ash put him on waivers, and poof! - he was gone, to go on hitting home runs (89 over the next three years) and driving in runs (296 over the same period) elsewhere. And while I liked Josh Towers far more than he probably deserved, nothing has persuaded me to change my original selection here. That would be Damaso Garcia. We understand now that Damo wasn't nearly as good as we all thought he was, back in 1982. Garcia at his best was a .300 hitter who stole bases, but he had no power and almost never took a walk. But he seemed like the first player the team had come up with who was any good, a quality major league ballplayer, like the other teams had. You actually waited for his spot in the lineup to come around. Like Tony, he was gone much too soon.

8. The late John Sullivan came to Toronto from Atlanta with Bobby Cox to be the bullpen coach in 1982. He finished his coaching career by catching Joe Carter's home run in the Jays bullpen to end the 1993 World Series, which is a nice way to wrap it up. (Earlier in 1993, Gaston had taken Sullivan to his first All-Star game as one of his coaches.) Obviously, Sully took the number away from the players for a good chunk of the team's history. And while Cavan Biggio is hanging in there, he hasn't done enough to dislodge my original selection. The Blue Jays have had two shortstops named Alex Gonzalez. The second one came from Venezuela, a good player, but he was only here for three months. The original Alex Gonzalez was from Florida, he was here for eight years and that's the one. The first Alex looked like he belonged in a boy band - even a dope like me knew the girls would find him cute - and he was one of those players who were completely formed by age 19 and don't develop one little bit from that point forward. Which was a little disappointing. But he was a wonderful shortstop, and I have actually suggested - very quietly, this is a Blue Jays crowd - that he may have been the best defensive player at shortstop this franchise has ever had. That's probably not true - Tony Fernandez around 1985-87 was just amazing. But Gonzalez was really, really good out there.

9. The Blue Jays just love giving this number to catchers - Danny Jansen is the latest, and he was preceded by Rick Cerone, Bob Brenly, Darrin Fletcher, Tom Wilson, Gregg Zaun, and J.P. Arencibia. And Jansen still has a long way to go if he's going to dislodge John Olerud. Long John was always a good player, and is at least a marginal Hall of Famer. He had two extraordinary seasons that are so completely out of context with the rest of his career - 1993 in Toronto, and 1998 in New York - that they make the rest of it seem a little disappointing. The Norm Cash of his day. He was a very, very good first baseman who probably deserved more than the three Gold Gloves he eventually won.

10. Oh, this is a hard one. John Mayberry was the first Blue Jay to hit 30 HRs in a season and Dave Collins still holds the team record for stolen bases in a season. Not enough. We even have to snub a World Series MVP in Pat Borders, a failed infielder who still played in 17 MLB seasons. This is already getting painful, and it's going to get so much worse. How I can possibly overlook Edwin Encarnacion? After a couple of false starts wearing 7 and 12, he adopted this number for keeps and became Edwin Encarnacion. I am insufferably proud of myself for foreseeing back in September 2010 that Edwin could one day hit 40 HRs at a time when his career high was 26, and just a few short weeks before the Jays let Oakland claim him on waivers. (Luckily, they were able to get him back.) I'm not having any fun here - this is almost as awful as 19 is going to be. But I still have to go with Vernon Wells. By the end of his time here, we were mostly just relieved to be rid of his contract. We should instead remember how good he was at his best. I mean, seriously - a Gold Glove centre fielder who hits .300 with 30 HRs? What the hell do you want from a ballplayer? Wells was one of those guys who was much faster than he looked - he was built like a fullback - and he was one of the smartest, most alert players on the diamond the team has ever had. He was a real treat to watch in person, and of course I got to see a lot of it. One of just five Jays ever to knock out 200 hits in a season, and he still holds the team record with 215 in 2003.

12. It's hard to even think about Roberto Alomar now. He was such a special player, one of the very best in franchise history - but his post-baseball life came to such disgrace as to see him banished from the game. His number was retired for a time, but Jordan Hicks was wearing it last year so it's presumably back in circulation. With Alomar banished, we're fortunate to have a good alternative. The Blue Jays took Ernie Whitt out of the Boston organization in the 34th round of the original expansion draft, back in November 1976. He was a 24 year old catcher who had just made it to AAA that year. Expectations probably weren't too high. Ah, but after the Jays traded Alan Ashby to the Astros and Rick Cerone to the Yankees, someone had to catch. It was Bobby Cox who figured out what Whitt could do - a decent job behind the plate, a little sock as the LH half of a platoon. His injury in the final week of the 1987 season was the second and final crippling blow that year.

13. On the broadcast the other day, Dan Shulman and Buck Martinez were talking about player superstitions and Shulman innocently asked if Martinez had any. Buck laughed and pointed out "I wore number 13." Maybe he should have reconsidered. He was the manager who was fired immediately after winning his 100th game; he's the player whose career is best remembered for a play in which he broke his leg. Well, it was an unforgettable play. It happened late at night in a West coast game that wasn't televised back here (there are now clips on the YouTube, but don't watch if you're at all faint of heart.) All we had was Tom Cheek describing the action - Thomas singles to right, Bradley tries to score from second, Barfield throws home, and Bradley crashes into Martinez as he's tagged out. Martinez is obviously badly hurt but now Thomas is heading for third, so Martinez, almost flat on his back, throws in the general direction of third base. The ball skips into left field, so Thomas rounds third and heads for home. George Bell scoops up the baseball and fires it home - and somehow Buck, in godawful pain, barely able to move, reaches up, snags the throw, and tags out Thomas, who was thoughtful enough to try to tip-toe around his fallen former teammate. Come on, it's an incredible play. Martinez was a superb defensive catcher, which is the only way you get to play for 17 years when he hit the way he did, although he did manage to punish a few southpaws from time to time. He's not nearly as highly regarded as a broadcaster as he used to be, but he's still very good when he stays in his lane or when the discussion gets down to his own special interest, which is the eternal battle between the hitter and the pitcher. Which remains, as always, the beating heart of the game.

14. Currently being worn by the manager, and John Schneider can only hope he lasts longer in the job than Carlos Tosca, the other manager who wore this number before him. The best player, by far, was David Price for two memorable months in 2015. But it was just two months, so we'll acknowledge the man who gave up his number to Price for those two months and donned it again when Price was gone. Justin Smoak was generally regarded as a disappointing underachiever for the first seven years of his MLB career. He was supposed to be a slugging first baseman, but he'd hit .224/.308/.392 with just 106 HRs in more than 800 games. The Blue Jays picked him up on waivers and his first two years here were nothing special. But at age 30, something clicked and he gave the Jays a couple of very fine seasons as the rest of the 2015-16 team slipped into decrepitude, and even got to play in an All-Star Game.

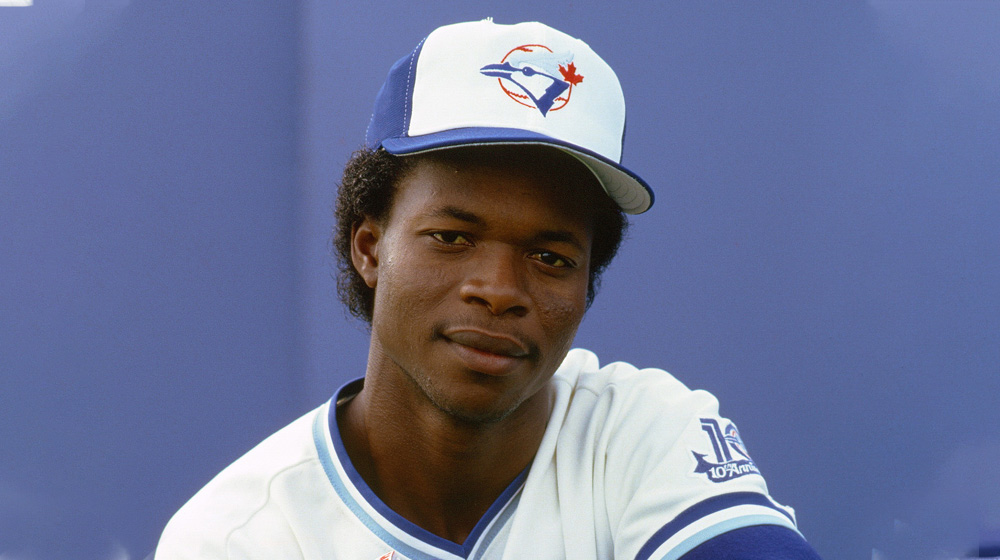

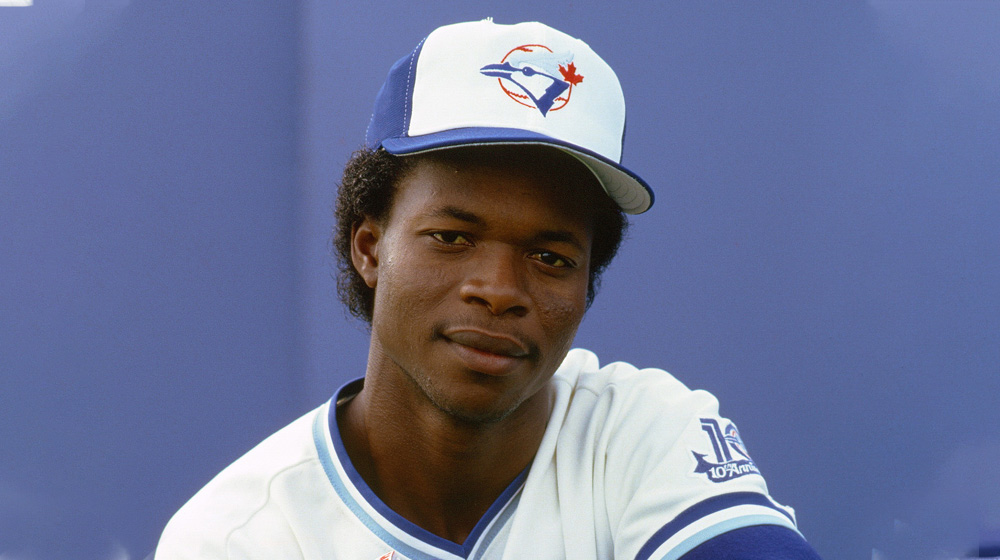

15. Alex Rios and Shawn Green both made it to All-Star games as Blue Jays, and both had some exceptional years here, but Lloyd Moseby still stands very high on the franchise's leader boards, in not insignificant categories as Games Played, Runs Scored, Hits, Doubles (fourth in each one), Walks (third), and Stolen Bases (first). He was pretty well the only one of Pat Gillick's high draft picks (second overall in 1978) who was any good at all. As is well known, the Jays called him to the majors when he was just 21, at least two years before he was even close to being ready, and let him play very, very badly for three years before he figured it all out. Nowadays teams do their best to manipulate and preserve service time - Gillick's Jays seemed to prefer lighting it on fire. But once Moseby's game came together, in 1983, he was possibly the most complete player of that rightly fabled outfield of the 1980s. And the Shaker was just a fun player to have on your team, and that ought to count for something, too. Just like Bell and Barfield, playing every day on the concrete at the Old Ex ground him into dust pretty quick - Moseby played 650 games there, and was just 31 when his MLB career ended.

16. Yusei Kikuchi, as we speak, seems to be in the process of giving the Blue Jays his second very good season, and if his form holds, that will make exactly three good seasons from a Blue Jay wearing this number. One was provided by Kikuchi himself in 2023. The other was Garth Iorg in 1985, when quite out of the blue he hit .313/.358/.469, a level of production he never even approached in his other eight seasons here. But Rance Mulliniks was unlikely to have done any better against the southpaws of the world, and Iorg was a useful backup and/or emergency option at second base. Played 931 games for the Blue Jays, the most of anyone who never played a single game for anyone else.

17. I'm pretty sure this will belong to Jose Berrios in the end - he's under contract through 2028, and I believe he's successfully came through the Change of Life, something I've long believed happens to quality RH pitchers as they get near age 30 - their stuff changes on them and it takes a year or so to figure out how to get batters out with their new tool kit. Berrios went through that in 2022, he's a different pitcher now, and he's just as effective as ever. For now, we will still salute Kelly Gruber. His peak didn't last very long - the doctors basically called off his career soon afterwards. But it was quite a peak, and his 1990 season was certainly the best ever by a Jays third baseman until Josh Donaldson came to town. He was always a superb defender, a very fine baserunner, and in 1990 he had as many huge, game-altering hits as any Jay ever had in any season.

18. Always a favourite of mine, Diamond Jim Clancy toiled away for 12 seasons as a Blue Jay, spending half of those seasons pitching for some truly awful teams. Clancy always seemed so big and durable and steady - in fact, he was streaky as all hell and three of his seasons here were torn up by lengthy spells on the DL. He was strictly a two-pitch guy - fastball, slider - and while both pitches were good, neither were elite which meant that he could really struggle if neither was working on a given day. (But the hitters still complained about that heavy fastball of his.) Clancy still stands high on the franchise leader boards, in wins, strikeouts, shutouts (third), starts, innings, complete games (second) - and of course he lost more games than anyone too. You can't hold that against him. He was here in 1977. And 1978. And 1979, 1980, and 1981. It pleases me that he was able to win a World Series game before he was done, wearing an Atlanta uniform for Bobby Cox.

20. Al Woods hit a pinch-hit HR in his very first major league at bat, which is pretty cool. Ken Huckaby put Derek Jeter on the disabled list, which is pretty cool if you like that sort of thing, and many probably do. Rob Ducey put himself on the disabled list running into the wall. My best option back in the day was Brad Fullmer. So Josh Donaldson made this pretty easy. He wasn't here that long, a month short of four seasons, and injuries chewed up the last two - but surely everyone remembers what a tremendous player he was in 2015-16.

21. Carlos Delgado adopted this number (he started out wearing 6) in honour of Roberto Clemente during his first season as an every day player, but he didn't keep it long. He gave it up after one year to accommodate his new teammate, a veteran pitcher signed as a free agent because his old team thought he just might be on the down side of the slope. And so Roger Clemens came to Toronto as a man on a mission - he was going to prove all those doubters wrong. Whatever it took, and it may have taken some measures generally frowned upon. But admit it - we enjoyed the hell out his Vengeance Tour in the moment. It was a two year Reign of Terror inflicted on all those poor unfortunate AL hitters. No Blue Jay pitcher has ever been better, and it's not remotely close.

22. Nothing new here. Jimmy Key spent one year as a LOOGY (wearing 27) before emerging as the best lefty in team history. He just knew how to pitch, mostly with a sinker, a curve, and a changeup. None of his pitches were outstanding, but they were good enough. He won 110 games for the Blue Jays and two more in the 1992 World Series. Key was 31 years old by then and Pat Gillick had decided to never sign a pitcher to a deal in excess of three years. So Key signed with the Yankees for four years. He would pitch for another six seasons, go 70-36, 3.67, and help the Yankees win another World Series. Like they needed another championship. Key was the runner-up (to Roger Clemens) for the 1987 Cy Young; as a Yankee, he was the runner-up (to David Cone) for the 1994 Cy Young.

23. Dave Lemanczyk was the Jays first decent starting pitcher, and Candy Maldonado helped win a World Series. Cecil Fielder started his mythic career right here. The best, however, was probably Jose Cruz. Junior was probably over-hyped upon arrival, and consequently always seemed something of a disappointment - he wsn't as good as his father, and he wasn't even as good as you thought he could be. But for all that, he was still a pretty decent player. We all had very high hopes for Brandon Morrow as well, and were similarly disappointed.

24. Tom Underwood was the Jays original hard-luck lefty. Strangely enough, his luck didn't improve when he moved to the Yankees. Dave Righetti finished his major league career here, demonstrating beyond a shadow of a doubt that he was done like dinner. Glenallen Hill fought with the spiders, and Turner Ward extorted riches out of Rickey Henderson for the rights to this very number. Ricky Romero wore this number with distinction for three fine seasons before it all went bad on him. Which means that the best Blue Jay is still Shannon Stewart. Stewart never became quite the player I thought he would - he developed in a different direction - but he was pretty good, thank you very much. Gord Ash made him wait in Syracuse for almost two years, because he was blocked by Freaking Otis Nixon, and J.P. Ricciardi would eventually trade him to Minnesota for Freaking Bobby Kielty. In between, Stewart spent five full seasons as the Jays leadoff hitter and left-fielder, hitting .305/.371/.451, scoring 100 runs and stealing 30 bases a year.

26. Back in the day, Willie Upshaw was a pretty easy choice - he was a Rule 5 pick from the Yankees back in 1977 who emerged as a regular in 1982 and as a star - .306/.373/.515 with 27 HR and 104 RBI - in 1983. He was first Blue Jay to score 100 runs in a season and the first to drive in as many as well. But his game slowly declined from that point, a little more each year, until he was just the guy blocking McGriff and Fielder from playing time. Adam Lind had a better run here. As I'm sure you all remember, Adam was a weird player. He had two outstanding years with the bat, posting an OPS+ better than 140 - in one of those seasons he hit 35 HRs and in the other he hit 6. He was a complete klutz with a glove on his hand, no matter where you put him, but he always gave a good effort.

27. You're all pretty familiar with Vladimir Guerrero Jr - we often seem to spend much of our time these days discussing him and his game. He's the Mitch Marner of the Blue Jays. So I'll change the subject. Guerrero this year has begun, cautiously and tentatively, using English when speaking to reporters - at least to ones he knows to be friendly, like Hazel Mae. Previously he had always chosen to speak through an interpreter, as has become the custom for many modern players. And I just want to say - I don't blame them. Not one little bit. No one ever wants to sound stupid, and almost no one sounds smart speaking a second language that you don't normally use in everyday life. Players also don't want to make a mistake, and say something that creates a problem. And they're taught to believe that a good chunk of the media is looking to create problems, to stir up trouble - and they're not wrong. It used to sell newspapers, it does whatever it does these days. The media used to grumble about Joe Carter; they appreciated that he was always professional and accommodating; but Joe was also a cliche machine, a guy who had all the Bull Durham lessons tattooed on his soul. They very much preferred someone like George Bell, a man who had no filter whatsoever. George's mouth did create a few problems, for himself and the team, which always seemed a strange way to repay him for his candour.

28. People were angry at Al Leiter for leaving town as a free agent after 1995 for years - make that decades - afterwards. Not me, but helping a team win a World Series goes a very long way at my house, and Leiter is one of five men who have won a World Series game for the Blue Jays. He was damaged goods when he arrived, and it took years for him to fight his way back onto the field - there were a couple of setbacks - but he would eventually demonstrate just why he was such a hyped prospect as a young Yankee, and why the Blue Jays were willing to give up Jesse Barfield to get him. He was a big southpaw with a powerful fastball who spent his entire career fighting his control (save for those years when Mike Piazza was his catcher.).

30. Carter wore this number in Cleveland and Devon White wore it for the Angels. But when they came to Toronto, it was being worn by Todd Stottlemyre. This was the number Todd's father Mel wore during his fine career as a Yankee pitcher. Todd wasn't quite as good as his dad, but he did win 138 games over 14 MLB seasons. He actually had his best years after leaving Toronto, but he was a rotation starter on both championship teams and provided some brilliant work out of the bullpen in the 1992 post-season. His World Series start a year later, and his baserunning misadventure that same evening - well, let's not dwell on that.

33. I don't really want to stick with Ed Sprague here, but while a number of players took this number and played very well in every case they did so for a very brief period - Doyle Alexander (1984-85), David Wells (1999-2000), Scott Rolen (2008-09), J.A. Happ (2016-18). I quite like Trevor Richards, but he's a middle reliever. Sprague wasn't much of a defender and he was a GIDP machine who had only one passable season with the bat - still, he was the regular third baseman for one championship team and he came off the bench to hit a huge pinch-hit homer in the Series the year before. It will have to do.

34. Dave Stewart was 36 years old and well past his prime when he came to town - he managed one adequate season, although he did rise to the occasion in the 1993 post-season. Kevin Gausman, here right now, is much closer to being near the peak of his powers and has already done more here than Stewart did. Except in the post-season, but we can still hope he gets a chance to rectify that.

35. Pickings were so slim here that in my first go-round I went with Phil Niekro (0-2, 8.25 as a Blue Jay) entirely on the basis of what he achieved elsewhere. Now we can remember Lyle Overbay, who briefly gave up this number to accomodate Frank Thomas when the Big Hurt joined the team and took it back when Thomas was gone. Overbay was a LH line drive hitter, generally a solid complementary bat, and a fine first baseman with one of the best arms we've seen at that position here - only Olerud and Guerrero come close.

36. I have long regarded Jerry Garvin as a classic what-if story - in his case, it's what if he had come up in a different time. But Garvin was born in 1955, was drafted by the Twins out of high school and made his pro debut at age 18 in the MidWest League, where he went 14-7 in 25 starts, throwing 163 IP. A year later, still a teenager, he went 17-5 in 25 starts for Reno, throwing 201 IP. He spent his age 20 season making 30 starts at two levels, going 15-12 in 233 IP. Toronto then chose him in the original expansion draft. He was still just 21 years old and in his rookie year he went 10-18, 4.19 in 34 starts and pitched 244.2 IP. He's mostly remembered for his incredible pickoff move - he picked off 35 baserunners that year (12 were recorded as Caught Stealing) - but it was also a very fine performance as a pitcher, on an awful team with an awful defense. But you can guess what happened - you see how young he was and how hard he was worked. He broke down the next year. He fought his way back to have a good year out of the bullpen for the 1980 team, but he was finished by age 26. What if... well, I wouldn't have to fall back on David Wells right here. This at least was Wells Mark I from 1987-1992, who moved from the bullpen to the rotation and back. The one who didn't look so much like a professional wrestler.

38. Way back in the day, this was worn by Balor Moore and Jim Gott. More recently it was Robbie Ray's number during his Cy Young season in 2021. But in 1986, 38 was given to a failed starter (wearing 28) trying to salvage his career as a submarining reliever. That worked out pretty well for Mark Eichhorn, who in 1986 had one of the greatest seasons any relief pitcher has ever had, in the long history of the game - he pitched 157 innings in 69 appearances and went 14-6, 1.72 with 10 Saves and ERA+ of 246. It was positively hilarious watching RH batters attempting to cope with the stuff he was serving them - they hit .135/.186/.165 against him in 323 Plate Appearances. By 1988 he'd lost his effectiveness and was back in the minors; he was sold to the Braves, released, signed by the Angels and in 1990 began to recover his form. He was traded back to Toronto in mid-season 1992 and worked out of the bullpen in both post-season series (he was used very sparingly, just one appearance in all four series.)

39. The original Canadian Blue Jay, and Tony LaRussa's long time coach in Oakland and St Louis, Dave McKay wore this in the beginning. And big Dave Parker wore it during his two weeks in Toronto. Since then... Erik Hanson? Steve Parris? Kevin Kiermaier has it now. I suppose our best bet has to be Gustavo Chacin, who had a very fine rookie season back in 2005 before arm injuries laid his career to waste.

40. Worn almost exclusively by pitchers over the years - Chris Bassitt wears it now - only one of whom is really worth remembering. That would be Mike Timlin, who may not have been suited to the Closer's role, although he did the job for a couple of teams. He wasn't a strikeout pitcher at all - he relied on a hard sinker and his control, which just got better and better as he got older. He was a reliable bullpen arm for 18 seasons, and pitched for the winning side in four World Series - the Jays in 1992-93, and the Red Sox in 2004 and 2007. And he was pretty good at coming down off the mound to field a bunt.

41. Pete Walker - the longest serving pitching coach in the majors - has this now. He wore it when he played as well, and it was also worn by Al Widmar, the team's first long-time pitching coach. The players haven't had all that much opportunity - it was recently worn by Aaron Sanchez when he looked like the team's Next Great Ace. But obviously the greatest Blue Jay here was Pat Hentgen. He didn't have the greatest fastball, or the best breaking pitches, or the best control - everything was a little ordinary. But oh, did he compete. He's one of just five men to win at least 100 games for the Blue Jays (Stieb, Halladay, Clancy, and Key are the others) and he was the team's first Cy Young winner in 1996. Gaston worked him very, very hard in 1996-97 and his form fell off pretty sharply after that. After an 11-12, 4.79 year in 1999 Gord Ash traded him to St. Louis because... well, I guess he really wanted that backup catcher.

42. Before the number was retired across major league baseball, it had only been worn by two Blue Jays players: Paul Mirabella came over fom the Yankees in the Rick Cerone trade and was expected to step into the rotation. He stepped in something - he went 5-12, 4.34 - and was traded to the Cubs a year later. And Xavier Hernandez wore this when he made his MLB debut with the 1989 Jays. The Astros grabbed him that winter in the Rule 5 draft, and he had a couple of fine seasons in their bullpen. By far the most distinguished service by anyone wearing this for the Blue Jays was that of Galen Cisco, who succeeded Widmar as the pitching coach in time for the championship years. No disrespect to Cisco, but I have no problem in sticking with Jackie Robinson.

44. It was Henry Aaron who made this into a traditional slugger's number - Willie McCovey and Reggie Jackson were among the first to follow his example, and in Toronto it recently adorned the broad back of Rowdy Tellez. The most memorable of the bunch was the notorious Cliff Johnson. Heathcliff (we called him that because he was not exactly the handsomest man in the major leagues) was especially notorious for borrowing his teammates bats without permission, which seems to make these guys lose their minds. But the man could hit. He couldn't do anything else, and half his career was wasted as teams tried to make him into a catcher. Otherwise he might have hit 400 career homers. Aside from the sluggers, it's also been a relief pitcher's number, from Tom Buskey to Frank Wills to Billy Koch to Aquilino Lopez. The best of the bunch was Casey Janssen. He came to the team as a starter in 2006, and had a tremendous season in the 2007 bullpen. He lost most of the next two years to a shoulder injury, but had made it back as a decent bullpen option by 2010. And in 2012, having run out of options, John Farrell began using Janssen to close the games. He proved to be really good at it. He carried on doing an outstanding job in this role for Gibbons in 2013 and the first half of 2014, when he got seriously ill at the All-Star Break and stunk out the joint for the rest of the year. And he was never any good again.

45. A pitcher's number that has had trouble finding decent pitchers to wear it. The fact that I even mention Jose Nunez and Rob MacDonald kind of gives that away. Thomas Pannone and Mitch White were only the most recent in a dreary line. Kelvim Escobar was the exception. He arrived in mid 1997, a 21 year old out of AA, and within weeks he was Cito Gaston's Closer and a good one (Gaston was almost never wrong about these things.) He began 1998 as Tim Johnson's main setup guy, taking the game to the new Closer Randy Myers. But he got hurt, missed two months - and was put into the starting rotation when he came back, as Juan Guzman had been traded away. He spent 1999 in Jim Fregosi's rotation, which is where he began in 2000 - but in August, with a 7-13, 5.42 mark, Fregpsi sent him back to the bullpen. Buck Martinez was his next manager. Escobar spent the first four months of 2001 working out of the pen and after a hot start pitched pretty badly for the rest of the first half. But he started pitching well again after the break, so they put him back into the starting rotation for the final two months. In 2002, Martinez put Escobar back in the Closer's role, and he did that job all year, for both Martinez and Carlos Tosca who took over in early June. He did okay - 38 Saves in 46 opportunities. So what did they do with him in 2003? Well, he began the year as the Closer once again, but had a few rough outings, and in May Tosca moved him back into the rotation. He did quite well there (12-8, 3.92) and when the season was over he was a free agent. Do you think he came back to Toronto? Would you, after all that? Not bloody likely. He spent the rest of his career with the Angels and had a couple of very fine years in their rotation before his arm gave out at age 31, after he'd gone 18-7, 3.40 for the 2007 team.

46. A variety of pitchers of little repute, many ofthem left-handed, have worn this number - Gary Lavelle was probably the best of them. We'll take a moment here to remember the late Mike Flanagan, a longtime fixture in Earl Weaver's rotation, winner of the 1979 Cy Young Award. He came to Toronto, a grizzled old pro, for the 1987 stretch run and he pitched brilliantly in that final month. The ensuing disaster was definitely not his fault. As we know, Flanagan came to a very sad end - I'd much rather remember what a competitor he was.

47. This was the number was adopted by the talented but generally impossible Junior Felix during his second Toronto season, but it was most memorably worn by Jack Morris in 1992 when he became the first Jays pitcher to win 20 games. More importantly, he single-handedly carried the faltering staff on his back through the entire month of August. They don't make it to the Promised Land without him.

48. The first man to throw a pitch for the Blue Jays was Bill Singer, who was washed up by that time. Pat Gillick had almost traded Singer to the Yankees for Ron Guidry but Peter Bavasi wouldn't let him. Luis Leal had a often effective six year run in Toronto, that ended suddenly in 1985. But we have to give the nod here to the all-seeing, all-knowing, Q. Gord Ash had traded Howard Battle to the Phillies for Paul Quantrill, thinking he had found a third starter. Quantrill went 4-9, 6.20 in that role, and Cito Gaston decided that he was best suited to the bullpen. Which he was, as it turned out. At his peak, Q could pitch 80 games a year - the more often he pitched, the better he pitched - and he'd walk a batter about once every two weeks. Every bullpen should have an omnipotent one. Q just kept firing those sinkers on the low outside corner, and the hitters kept beating them into the ground because there's nothing else you can do with that pitch.

49. Tom Filer had a memorable 7-0 run for the 1985 Jays, and Tom Candiotti pitched very well after he was brought in to fill the shoes of the injured Dave Stieb in mid-1991. But both men only had partial seasons here, and Tony Castillo during his second Toronto tour from 1993-96 was absolutely my favourite player to watch in those days. The most relaxed man on a pitching mound I have ever seen. He always looked like he was trying to stifle a yawn, or remember where he'd put his socks. I loved it, and I can't explain it.

51. Back in the day, my best option was Trever Miller. Then came Jesse Litsch, whose career began with a lot of promise until - as happens to so many young pitchers - his arm stopped working. But Ken Giles was even better. He was what came back to Toronto when they sent Roberto Osuna away in 2018, and Giles was even better. The following year he was sailing along, doing an outstanding job for a team quite unworthy of him. But at the beginning of July, he pitched on three successive days for the first time in three years. Some pitchers can do that - Shawn Camp and Paul Quantrill did it here. But Giles threw much, much harder than those guys and didn't figure to be one of them. He had also just returned from a brief stint on the IL with a tender elbow, which immediately resumed barking at him in protest. The elbow blowed up real good at the very beginning of the following season, and Giles is still trying to find his way back. But for that one year, he was as good as any reliever this team has ever had.

52. One of the best, and most remembered pitching performances by a Blue Jay was by someone wearing this number. It was Roy Halladay, making his second career start on the last day of the 1998 season - we know it as the Bobby Higginson game - Doc was one out away from a no-hitter when Higginson homered into the Blue Jays bullpen. He wasn't Doc yet, and I always thought his best game as a Blue Jay was a two-hit shutout against the Twins in May 2005. He gave up a first inning bunt single to Punto and a sixth inning infield hit to Stewart - and a better third baseman than Hillenbrand probably turns both plays into outs. He didn't go to Ball 2 on a single hitter until the sixth inning. The Twins hit two balls past the infield all night - a fly to centre in the first, a fly to right in the ninth. He struck out 10, didn't walk anyone, and needed just 99 pitches to get it done. But I will always think the best single game performance by a Jays pitcher came from Dave Stieb in August 1989. It wasn't the no-hitter, or even one of the many one-hitters. It was the Roberto Kelly Game - one out away from a perfect game, Stieb lost it on Kelly's double to left. He ended up with a complete game two-hitter with 11 Ks and he needed just 90 pitches to get all those strikeouts. Stieb was famous, and rightly so, for his slider but by 1989 he'd come up with this big curveball. On this night I swear at least half of what he threw were these ridiculous curveballs that seemed to start well above the batter's head and then plummet suddenly through the strike zone. There was no point whatsoever in swinging at the thing, and the Yankees hitters wisely chose not to. But Stieb kept throwing it for strikes. It seemed like he was ahead 0-2 to every hitter. Oh, it was just a great night at the park, and the moan of despair from the crowd when he lost the perfecto - unforgettable. Back in the day I had to celebrate John Frascatore for this number. He didn't do very much worth remembering but he did win three games in three days - June 29, June 30, and July 1, 1999 - which doesn't happen very often. Now we can go with B.J. Ryan, who gave the Jays a sensational season in 2006 before - guess what happened - yeah, his arm broke down. Ryan was a huge pitcher who seemed to be throwing the ball 100 mph - in fact, he had trouble breaking 90 but it was so hard for the hitters to find the ball out of his hand that he might as well have been breaking the sound barrier with his pitches.

53. Pitching for both Chicago teams, Dennis Lamp allowed Willie McCovey's 513th homer (at the time, the NL record for LH batters), Lou Brock's 3000th hit, and Reggie Jackson's 2000th hit. The Jays signed him to be their closer in 1984. That didn't work out, but in 1985, he and his sinker moved into middle relief and fared much better. It's hard to be better than 11-0.

54. We're done with Roberto Osuna in these parts, and Woody Williams had a nice career - unfortunately most of that niceness came in the NL once Dave Stewart persuaded Gord Ash to trade Williams for Joey Hamilton. Instead we have the man who pitched in more games for the Blue Jays than anyone else in franchise history - it's Jason Frasor time. He was a little (5'9) right-hander out of Southern Illinois, drafted by Detroit in the 33rd round in 1999. He lost a year to Tommy John surgery and was eventually traded to the Dodgers, who converted him to a reliever and moved him up to AA, where he did just fine. So they traded him to Toronto, for a big catcher-outfielder named Jayson Werth. Frasor opened the 2004 season in AAA Syracuse, but was quickly promoted to the majors and before long he was Carlos Tosca's closer. He didn't hold that job, but he was a solid performer in the Jays bullpen through the Gibbons years, the Return of Cito, and the beginning of the Farrell era, and ended up appearing in 505 games as a Jay. He wandered around the league for the final five years of his career, which included a brief return to Toronto. He finally made it to the post-season with the Royals in 2014, and made three appearances in the World Series. He began the next year in Kansas City, but they released him in July (huh? he had a 1.54 ERA at the time) and he finished his career that year in Atlanta.

55. The Blue Jays got Russ Martin at the end of his career, and we all suffered together as he declined into a fellow who couldn't even crack the Mendoza Line. But for a couple of years there, he was the best catcher the team has ever had. The very few who could match his defense - Buck Martinez, Charlie O'Brien - couldn't carry his bat. The few that could match him at the plate - Darrin Fletcher comes to mind - couldn't carry his glove. But it grieves me to put John Cerutti to the side. I have fond memories of him from my press box days. I spent some twenty years there, and there were generally three kinds of people that I encountered. There was a group that was - let's say standoffish (no one was ever rude.) But I didn't travel with the team, I didn't go down to the clubhouse and this group - Gord Ash, Tom Cheek, John Lott - didn't know who I was, what I was doing and they weren't that interested in finding out. There's another group who were generally helpful and approachable if you needed them - J.P. Ricciardi and Buck Martinez come to mind - and finally there were some plain friendly people - Jerry Howarth, of course, but Don Martin from Global TV, Larry Millson of the Globe, and Jeff Blair (Blair was a hoot!) John Cerutti was one of those guys. I even managed to stump him once with a trivia question about his own career. And Cerutti was just becoming a good broadcaster when he passed away so suddenly - he was very tense and unsure of himself in his first few years on the job, and working with Brian Williams couldn't have helped (Williams was certainly a fine broadcaster, but his specialty is the Olympics, where everything is a huge deal - they only do them every four years - which is not too appropriate for baseball.) It's just wrong that he's not with us anymore.

Basketball requires special permission to wear numbers higher than 55, and I have always invoked that rule here. It's my story, I'll do what the hell I like. There have, of course, been any number of Blue Jays wearing oddball numbers. Most of the current bullpen in fact,: Pop (56), Green (57), Mayza (58), Romano (68), Cabrera (92) and Garcia (93). And Mark Buehrle (56) was always a favourite of mine, and clearly a charter member of the Hall of Very Good. The man achieved about as much as one can possibly achieve with an 85 mph fastball, mostly becase he did everything else - hold runners, field his position - about as well as it can be done.

The original Blue Jays entry that opened the Lobby. way back in May 2005 was just a casual one-off piece on uniform numbers, But I was younger then, full of vigour and energy and all that, and started doing sequels. I zipped through most of the AL East in a matter of weeks. And then I started getting carried away. As I do. I got into looking at team histories. I started finding cool pictures. I can't help myself.

So those very first entries, on the AL East teams, seem somewhat skimpy to me now. Especially the Blue Jays entry. And hey... it's been almost twenty years. Things have happened. I can report that many of my original choices for the Blue Jays edition of the Lobby retain their Position of Honour, but we've seen a few deserving fellows from these last two decades, who have been patiently awaiting their own place in these Unhallowed Halls.

So let's get to it.

1. No change here. Tony Fernandez wore number 1 during all four of his tours of duty, and we find his name all over the team record book: no one played in more games, no one had more hits. He started out as the defensive whiz who banged out 200 hits a year, only to lose much of his edge, and possibly much of his joy in the game, after a serious beaning in 1989. He came back just to fill a hole in 1993, and played brilliantly in the championship run. His third tour found him losing so much of his defensive skills that he had to be moved out of the middle of the infield, but he could still rip line drives at will. And he wrapped it all up with a memorable coda as a pinch-hitting specialist, receiving and giving back more fan affection than he'd probably ever known in his long and distinguished career. He was an amazing player before the beaning. Gone much too soon.

2. This had long been the number given to mediocre infielders - Fred Manrique, Luis Sojo, Danny Ainge, Dave Berg. Back in 2005, I went with Nelson Liriano, who had a nice season in 1989 as part of a second base platoon. We have better options now. Troy Tulowitzki, his defense especially, was a vital part of those 2015-16 teams. But a) Tulo couldn't stay healthy, and so b) the Blue Jays ended up paying him something like 113 million dollars to play 238 games. I'm not Warren Buffett, but that seems like poor return on investment, and it takes a bit of the shine off. So we're going to go with Aaron Hill here. He was drafted out of LSU with the 13th overall pick in 2003, and played shortstop in the minors. He made it to the majors in 2005, playing mostly third base in place of the often injured Corey Koskie. He got a long look at second base in September when Orlando Hudson was hurt, and he took over at second the following season once Hudson had been traded to Arizona. His offensive production here was unpredictable - as a Jay, he could hit anywhere from .205 to .291, as many as 36 HRs or as few as 6. His glove work never faltered.

3. Jimy Williams took this number out of circulation during his years as a coach and manager. For a long time the most noteworthy playing performance was turned in by Mookie Wilson during the 1989 stretch run. It was just two months, but he was on fire. Now, I think we'll single out Old Sparky. Reed Johnson wore this for his last three Toronto seasons, and the one in the middle (2006) was simply sensational - .319/.390/.479 - from someone who was supposed to be the fourth outfielder, but played far too well to take a backseat to anyone. I'll always remember him for what I thought of as Sparky's Tripod. It was the way he stood in the batter's box with his legs apart, the bat resting against his crotch while he adjusted his batting gloves.

4. George Springer had been making a pretty decent case, but I'm going to hold off. I don't think George is toast just yet, but I am alert to the possibility. For now, we'll stick with Alfredo Griffin. It's been twenty years, and Griffin has lost most oi the places he used to hold among franchise leaders. Except for triples and caught stealing, which totally figures. Alfredo was the most aggressive baserunner I have ever seen. If there was such a category as Insane Basepath Commando Raids - he'd be your man. ( I will always remember him scoring from second base on Sprague's infield ground out against Seattle.) Bill James once suggested that Griffin was the dumbest player in the majors - he showed no growth at all (his best season, by a mile, was his rookie year), he made tons of errors, he had no plate discipline, he was a terrible percentage base stealer. James was mystified by this, as he and everyone in baseball knew that Griffin was universally regarded as one of the brightest people around and nobody's fool - sharp as a tack, and very smart about money. Just not on a baseball diamond.

Incidentally, the historical record says that Griffin played in 982 games as a Blue Jay. This is wrong, and it will forever be wrong. It was 983. One day in 1992, he came off the bench to replace Roberto Alomar at second base for the final inning. I was in the press box scoring the game for STATS, and I duly noted the lineup change. Duane Ward got the final three outs on about eight pitches, none of which were hit anywhere near second base. Half an hour after the game the office was on the phone to me wondering why I was the only person on earth who had Griffin entering the game. Because he did, I said. But the official scorer hadn't noticed. Howie Starkman of Jays PR, who normally announced all these moves to the press box, hadn't noticed. Howie and I actually went and watched the video of that last inning and there was simply no shot of the second baseman. But I promise - there is no way on earth I or anyone else could have looked at Roberto Alomar and thought they were seeing Alfredo Griffin. No way whatsoever. So it definitely happened. But I'm the only who noticed.

5. No disrespect to John Gibbons, but we do have a worthy player here and so this is still going to be Rance Mulliniks. He didn't look like an athlete - he looked like the guy who did your taxes. Played 1,115 games for the Blue Jays (8th all time) and hit 204 doubles (10th all time.) He appeared in 11 seasons, hitting .280/.365/.424 and lasted just long enough to get a ring in 1992 (he was on the active roster for the World Series, but didn't appear in a game.)

6. First Marcus Stroman put in a claim, and now Alek Manoah is doing his best. But while Bobby Cox is in the Hall of Fame mostly for his work in Atlanta, he began to build his legend right here. As everyone knows, Cox was ejected from more games than anyone in MLB history. Why was that? What made him one the game's truly legendary yellers and screamers? Well, Bobby Cox really, really liked winning. And he got very, very upset at anything that interfered with that overriding goal - his own players, the other team, the umpires. When he arrived here in 1982, Cox actually expected his Blue Jays to win, and this - this was simply unprecedented. No one else expected it, no one had even considered the possibility. The thought simply hadn't occurred. It had occurred to Bobby Cox though, and he raised the bar for everyone.

7. Shannon Stewart and Edwin Encarnacion both wore this at the beginning of their Blue Jays careers before finding some other digit they liked better. Tony Batista had two remarkable seasons here. Then Batista had a bad first half in 2001, Gord Ash put him on waivers, and poof! - he was gone, to go on hitting home runs (89 over the next three years) and driving in runs (296 over the same period) elsewhere. And while I liked Josh Towers far more than he probably deserved, nothing has persuaded me to change my original selection here. That would be Damaso Garcia. We understand now that Damo wasn't nearly as good as we all thought he was, back in 1982. Garcia at his best was a .300 hitter who stole bases, but he had no power and almost never took a walk. But he seemed like the first player the team had come up with who was any good, a quality major league ballplayer, like the other teams had. You actually waited for his spot in the lineup to come around. Like Tony, he was gone much too soon.

8. The late John Sullivan came to Toronto from Atlanta with Bobby Cox to be the bullpen coach in 1982. He finished his coaching career by catching Joe Carter's home run in the Jays bullpen to end the 1993 World Series, which is a nice way to wrap it up. (Earlier in 1993, Gaston had taken Sullivan to his first All-Star game as one of his coaches.) Obviously, Sully took the number away from the players for a good chunk of the team's history. And while Cavan Biggio is hanging in there, he hasn't done enough to dislodge my original selection. The Blue Jays have had two shortstops named Alex Gonzalez. The second one came from Venezuela, a good player, but he was only here for three months. The original Alex Gonzalez was from Florida, he was here for eight years and that's the one. The first Alex looked like he belonged in a boy band - even a dope like me knew the girls would find him cute - and he was one of those players who were completely formed by age 19 and don't develop one little bit from that point forward. Which was a little disappointing. But he was a wonderful shortstop, and I have actually suggested - very quietly, this is a Blue Jays crowd - that he may have been the best defensive player at shortstop this franchise has ever had. That's probably not true - Tony Fernandez around 1985-87 was just amazing. But Gonzalez was really, really good out there.

9. The Blue Jays just love giving this number to catchers - Danny Jansen is the latest, and he was preceded by Rick Cerone, Bob Brenly, Darrin Fletcher, Tom Wilson, Gregg Zaun, and J.P. Arencibia. And Jansen still has a long way to go if he's going to dislodge John Olerud. Long John was always a good player, and is at least a marginal Hall of Famer. He had two extraordinary seasons that are so completely out of context with the rest of his career - 1993 in Toronto, and 1998 in New York - that they make the rest of it seem a little disappointing. The Norm Cash of his day. He was a very, very good first baseman who probably deserved more than the three Gold Gloves he eventually won.

10. Oh, this is a hard one. John Mayberry was the first Blue Jay to hit 30 HRs in a season and Dave Collins still holds the team record for stolen bases in a season. Not enough. We even have to snub a World Series MVP in Pat Borders, a failed infielder who still played in 17 MLB seasons. This is already getting painful, and it's going to get so much worse. How I can possibly overlook Edwin Encarnacion? After a couple of false starts wearing 7 and 12, he adopted this number for keeps and became Edwin Encarnacion. I am insufferably proud of myself for foreseeing back in September 2010 that Edwin could one day hit 40 HRs at a time when his career high was 26, and just a few short weeks before the Jays let Oakland claim him on waivers. (Luckily, they were able to get him back.) I'm not having any fun here - this is almost as awful as 19 is going to be. But I still have to go with Vernon Wells. By the end of his time here, we were mostly just relieved to be rid of his contract. We should instead remember how good he was at his best. I mean, seriously - a Gold Glove centre fielder who hits .300 with 30 HRs? What the hell do you want from a ballplayer? Wells was one of those guys who was much faster than he looked - he was built like a fullback - and he was one of the smartest, most alert players on the diamond the team has ever had. He was a real treat to watch in person, and of course I got to see a lot of it. One of just five Jays ever to knock out 200 hits in a season, and he still holds the team record with 215 in 2003.

11. This was worn by both Jeff Kent, when he began his fine career with the Jays, and the man Kent was traded for - David Cone, of course, such a key part of the 1992 team. Eric (Dude!) Hinske had his moments and Kevin Pillar was both a nice player, and a cool story (a 32nd round pick, now in his twelfth season.) Even as we speak, Bo Bichette is working on his own legend. But Bo's going to need to build one hell of a legend to dislodge one of my all-time favourites, the original Dominican redneck, the one and only George Bell. Bell could steal bases and throw out base runners when he arrived, but like Barfield and Moseby, his outfield comrades from the 1980s, he did not age well. I always wondered how much playing every game every year, half on them on the old Ex turf, had to do with that. Bell played 463 games on the concrete, and he was done by age 33. But while the rest of his game faded away, he kept right on hitting and he was one of my favourite hitters to watch, ever. He was just so cool in the batter's box. It was his house - the little waggle of the bat at knee level as he settled in, the way he coolly watched the first pitch go by almost every time ("let's see what you got"), the way he urgently required the umpire to check any baseball that even came near the dirt (they all do it automatically these days, of course.) No one like him.

12. It's hard to even think about Roberto Alomar now. He was such a special player, one of the very best in franchise history - but his post-baseball life came to such disgrace as to see him banished from the game. His number was retired for a time, but Jordan Hicks was wearing it last year so it's presumably back in circulation. With Alomar banished, we're fortunate to have a good alternative. The Blue Jays took Ernie Whitt out of the Boston organization in the 34th round of the original expansion draft, back in November 1976. He was a 24 year old catcher who had just made it to AAA that year. Expectations probably weren't too high. Ah, but after the Jays traded Alan Ashby to the Astros and Rick Cerone to the Yankees, someone had to catch. It was Bobby Cox who figured out what Whitt could do - a decent job behind the plate, a little sock as the LH half of a platoon. His injury in the final week of the 1987 season was the second and final crippling blow that year.

13. On the broadcast the other day, Dan Shulman and Buck Martinez were talking about player superstitions and Shulman innocently asked if Martinez had any. Buck laughed and pointed out "I wore number 13." Maybe he should have reconsidered. He was the manager who was fired immediately after winning his 100th game; he's the player whose career is best remembered for a play in which he broke his leg. Well, it was an unforgettable play. It happened late at night in a West coast game that wasn't televised back here (there are now clips on the YouTube, but don't watch if you're at all faint of heart.) All we had was Tom Cheek describing the action - Thomas singles to right, Bradley tries to score from second, Barfield throws home, and Bradley crashes into Martinez as he's tagged out. Martinez is obviously badly hurt but now Thomas is heading for third, so Martinez, almost flat on his back, throws in the general direction of third base. The ball skips into left field, so Thomas rounds third and heads for home. George Bell scoops up the baseball and fires it home - and somehow Buck, in godawful pain, barely able to move, reaches up, snags the throw, and tags out Thomas, who was thoughtful enough to try to tip-toe around his fallen former teammate. Come on, it's an incredible play. Martinez was a superb defensive catcher, which is the only way you get to play for 17 years when he hit the way he did, although he did manage to punish a few southpaws from time to time. He's not nearly as highly regarded as a broadcaster as he used to be, but he's still very good when he stays in his lane or when the discussion gets down to his own special interest, which is the eternal battle between the hitter and the pitcher. Which remains, as always, the beating heart of the game.

14. Currently being worn by the manager, and John Schneider can only hope he lasts longer in the job than Carlos Tosca, the other manager who wore this number before him. The best player, by far, was David Price for two memorable months in 2015. But it was just two months, so we'll acknowledge the man who gave up his number to Price for those two months and donned it again when Price was gone. Justin Smoak was generally regarded as a disappointing underachiever for the first seven years of his MLB career. He was supposed to be a slugging first baseman, but he'd hit .224/.308/.392 with just 106 HRs in more than 800 games. The Blue Jays picked him up on waivers and his first two years here were nothing special. But at age 30, something clicked and he gave the Jays a couple of very fine seasons as the rest of the 2015-16 team slipped into decrepitude, and even got to play in an All-Star Game.

15. Alex Rios and Shawn Green both made it to All-Star games as Blue Jays, and both had some exceptional years here, but Lloyd Moseby still stands very high on the franchise's leader boards, in not insignificant categories as Games Played, Runs Scored, Hits, Doubles (fourth in each one), Walks (third), and Stolen Bases (first). He was pretty well the only one of Pat Gillick's high draft picks (second overall in 1978) who was any good at all. As is well known, the Jays called him to the majors when he was just 21, at least two years before he was even close to being ready, and let him play very, very badly for three years before he figured it all out. Nowadays teams do their best to manipulate and preserve service time - Gillick's Jays seemed to prefer lighting it on fire. But once Moseby's game came together, in 1983, he was possibly the most complete player of that rightly fabled outfield of the 1980s. And the Shaker was just a fun player to have on your team, and that ought to count for something, too. Just like Bell and Barfield, playing every day on the concrete at the Old Ex ground him into dust pretty quick - Moseby played 650 games there, and was just 31 when his MLB career ended.

16. Yusei Kikuchi, as we speak, seems to be in the process of giving the Blue Jays his second very good season, and if his form holds, that will make exactly three good seasons from a Blue Jay wearing this number. One was provided by Kikuchi himself in 2023. The other was Garth Iorg in 1985, when quite out of the blue he hit .313/.358/.469, a level of production he never even approached in his other eight seasons here. But Rance Mulliniks was unlikely to have done any better against the southpaws of the world, and Iorg was a useful backup and/or emergency option at second base. Played 931 games for the Blue Jays, the most of anyone who never played a single game for anyone else.

17. I'm pretty sure this will belong to Jose Berrios in the end - he's under contract through 2028, and I believe he's successfully came through the Change of Life, something I've long believed happens to quality RH pitchers as they get near age 30 - their stuff changes on them and it takes a year or so to figure out how to get batters out with their new tool kit. Berrios went through that in 2022, he's a different pitcher now, and he's just as effective as ever. For now, we will still salute Kelly Gruber. His peak didn't last very long - the doctors basically called off his career soon afterwards. But it was quite a peak, and his 1990 season was certainly the best ever by a Jays third baseman until Josh Donaldson came to town. He was always a superb defender, a very fine baserunner, and in 1990 he had as many huge, game-altering hits as any Jay ever had in any season.

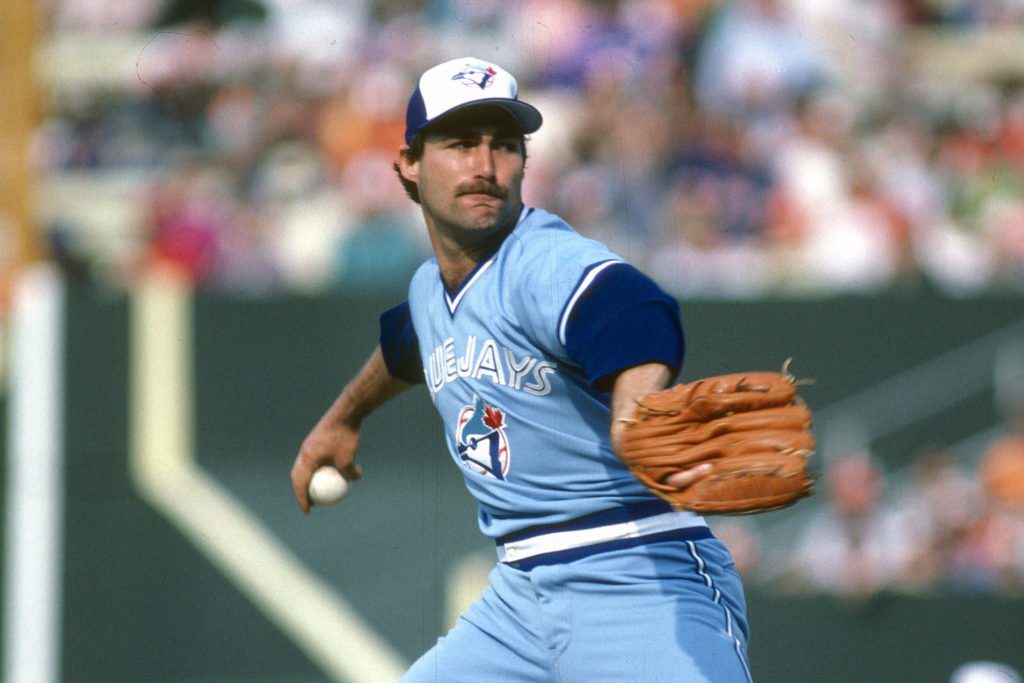

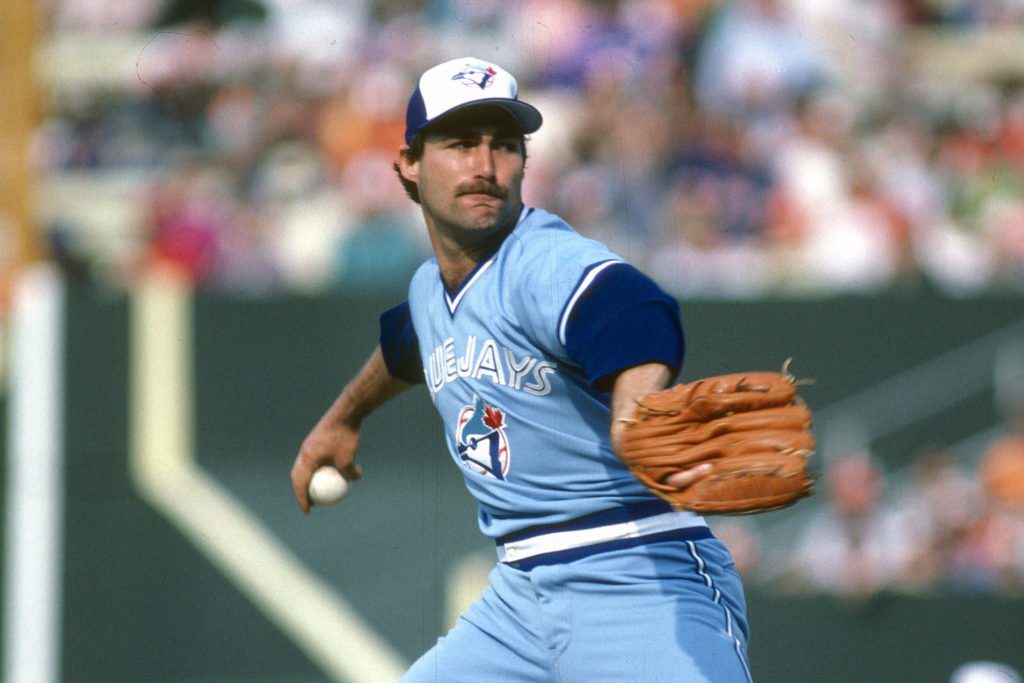

18. Always a favourite of mine, Diamond Jim Clancy toiled away for 12 seasons as a Blue Jay, spending half of those seasons pitching for some truly awful teams. Clancy always seemed so big and durable and steady - in fact, he was streaky as all hell and three of his seasons here were torn up by lengthy spells on the DL. He was strictly a two-pitch guy - fastball, slider - and while both pitches were good, neither were elite which meant that he could really struggle if neither was working on a given day. (But the hitters still complained about that heavy fastball of his.) Clancy still stands high on the franchise leader boards, in wins, strikeouts, shutouts (third), starts, innings, complete games (second) - and of course he lost more games than anyone too. You can't hold that against him. He was here in 1977. And 1978. And 1979, 1980, and 1981. It pleases me that he was able to win a World Series game before he was done, wearing an Atlanta uniform for Bobby Cox.

19. I remember trawling through almost a century of St. Louis Cardinal baseball and the best thing I could find for this number was a career backup catcher. Nineteen has a very different kind of legacy in Toronto. It began at the very beginning, way back in April 1977. That was when Otto Velez had what is still the greatest month of any hitter in franchise history - .442/.531/.865 - and in the very first month's of the team's existence! I've written about Velez before, of course. He's not our guy, though. Because this number was then worn by a genuine Hall of Famer (at last!), the great Fred McGriff - the Crime Dog hit the first homer ever struck at SkyDome. That figures - he also stole the first base, which doesn't. But McGriff's not our guy either. The number was then worn by another Hall of Famer, the very first man to come to the plate at SkyDome, where he promptly struck the very first hit (a double, off Jimmy Key.) Paul Molitor was wearing number 4 for the Brewers then, but the number was taken when he came to Toronto, so he chose 19 out of respect for his longtime Milwaukee teammate, Robin Yount. There was actually quite a bit of unhappiness in these parts, rumblings of discontent, when the Jays let Dave Winfield walk and signed Molitor instead. Really, there was., But no one who saw the way Molitor played in Toronto is going to forget it any time soon. Whatever his team needed, whenever they needed it... he delivered. Again and again and again. As great as his numbers were while he was here, and they were great indeed, they don't even hint at how well he played, and how much he meant to that team. What a player he was. But Molitor's not the guy either.

Come on, you know where I'm going with this! Do I have to say his name?

We'll remember Jose Bautista in these parts as long as we remember baseball. We'll always have Game Five.

"Did you see that? Did you see what I just did"

20. Al Woods hit a pinch-hit HR in his very first major league at bat, which is pretty cool. Ken Huckaby put Derek Jeter on the disabled list, which is pretty cool if you like that sort of thing, and many probably do. Rob Ducey put himself on the disabled list running into the wall. My best option back in the day was Brad Fullmer. So Josh Donaldson made this pretty easy. He wasn't here that long, a month short of four seasons, and injuries chewed up the last two - but surely everyone remembers what a tremendous player he was in 2015-16.

21. Carlos Delgado adopted this number (he started out wearing 6) in honour of Roberto Clemente during his first season as an every day player, but he didn't keep it long. He gave it up after one year to accommodate his new teammate, a veteran pitcher signed as a free agent because his old team thought he just might be on the down side of the slope. And so Roger Clemens came to Toronto as a man on a mission - he was going to prove all those doubters wrong. Whatever it took, and it may have taken some measures generally frowned upon. But admit it - we enjoyed the hell out his Vengeance Tour in the moment. It was a two year Reign of Terror inflicted on all those poor unfortunate AL hitters. No Blue Jay pitcher has ever been better, and it's not remotely close.

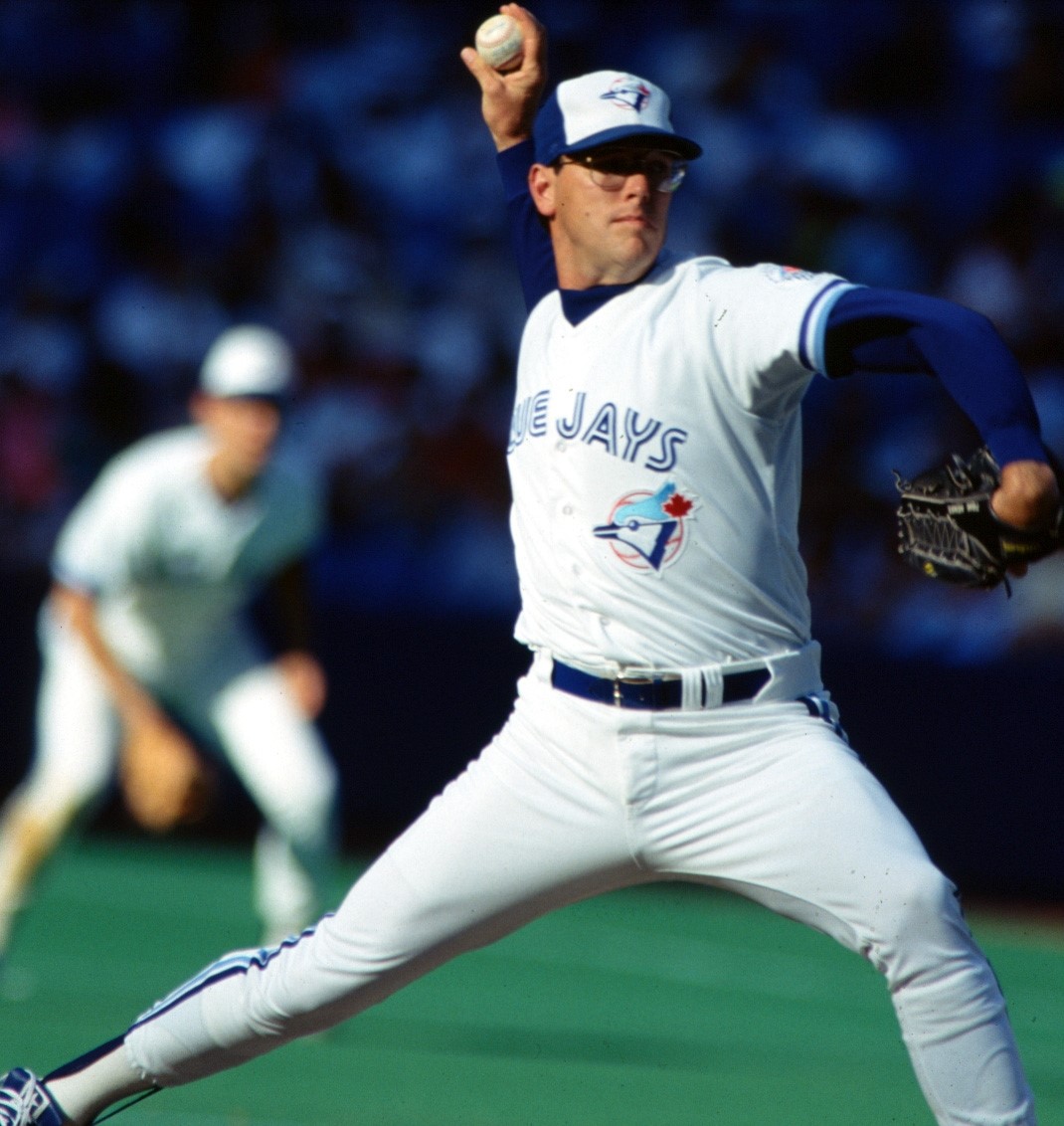

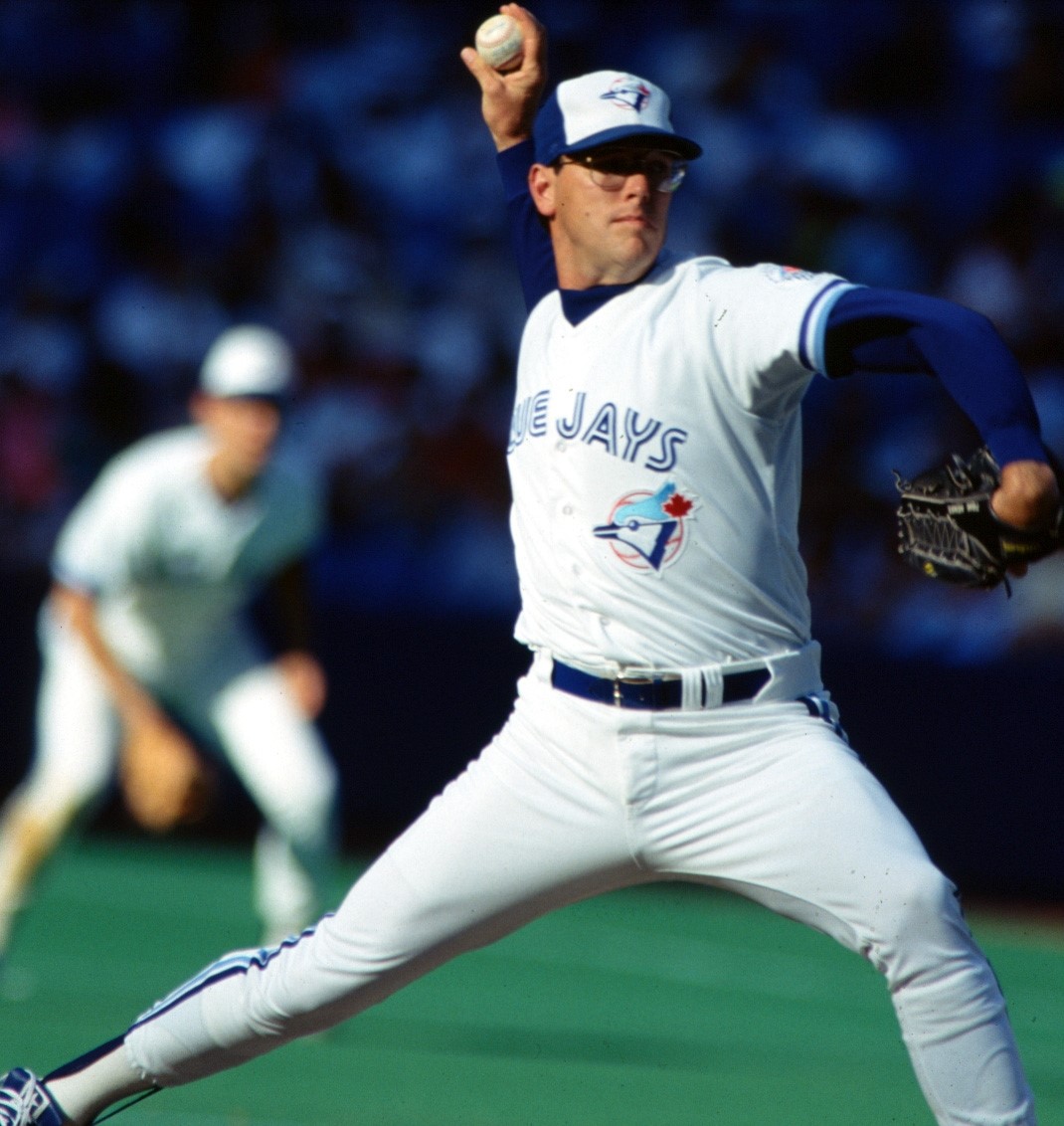

22. Nothing new here. Jimmy Key spent one year as a LOOGY (wearing 27) before emerging as the best lefty in team history. He just knew how to pitch, mostly with a sinker, a curve, and a changeup. None of his pitches were outstanding, but they were good enough. He won 110 games for the Blue Jays and two more in the 1992 World Series. Key was 31 years old by then and Pat Gillick had decided to never sign a pitcher to a deal in excess of three years. So Key signed with the Yankees for four years. He would pitch for another six seasons, go 70-36, 3.67, and help the Yankees win another World Series. Like they needed another championship. Key was the runner-up (to Roger Clemens) for the 1987 Cy Young; as a Yankee, he was the runner-up (to David Cone) for the 1994 Cy Young.

23. Dave Lemanczyk was the Jays first decent starting pitcher, and Candy Maldonado helped win a World Series. Cecil Fielder started his mythic career right here. The best, however, was probably Jose Cruz. Junior was probably over-hyped upon arrival, and consequently always seemed something of a disappointment - he wsn't as good as his father, and he wasn't even as good as you thought he could be. But for all that, he was still a pretty decent player. We all had very high hopes for Brandon Morrow as well, and were similarly disappointed.

24. Tom Underwood was the Jays original hard-luck lefty. Strangely enough, his luck didn't improve when he moved to the Yankees. Dave Righetti finished his major league career here, demonstrating beyond a shadow of a doubt that he was done like dinner. Glenallen Hill fought with the spiders, and Turner Ward extorted riches out of Rickey Henderson for the rights to this very number. Ricky Romero wore this number with distinction for three fine seasons before it all went bad on him. Which means that the best Blue Jay is still Shannon Stewart. Stewart never became quite the player I thought he would - he developed in a different direction - but he was pretty good, thank you very much. Gord Ash made him wait in Syracuse for almost two years, because he was blocked by Freaking Otis Nixon, and J.P. Ricciardi would eventually trade him to Minnesota for Freaking Bobby Kielty. In between, Stewart spent five full seasons as the Jays leadoff hitter and left-fielder, hitting .305/.371/.451, scoring 100 runs and stealing 30 bases a year.

25. Doug Ault was the first Blue Jays hero, and Roy Lee Jackson was the leader of the 80s chapel contingent. Devon White played centre field as gracefully and effectively as the position has ever been played. But seriously folks... Carlos Delgado remains the franchise's all-time leader in things like Offensive WAR, OPS, Slugging, HRs, Doubles, RBIs, Walks; he holds the single season leader marks in Slugging, OPS, Doubles; and he's the only Jay to hit four homers in a single game. He got started a little late - he played more than 600 games in the minors and didn't make it to the Show to stay until he was 24, mainly because the Jays persisted in believing he was the Catcher of the Future. And of course, a persistent hip problem ended his career a little early - in his last full season, at age 37, he bashed 38 HRs and drove in 115 RBIs. He finished with 473 career homers, and was one-and-done on the HoF ballot in 2015. Fools! You have no perception. (A shocked Jayson Stark said Delgado was "the best player in history to get booted off the ballot after his first year.") Puerto Rico has produced a lot of great major leaguers. None of them hit more homers.

26. Back in the day, Willie Upshaw was a pretty easy choice - he was a Rule 5 pick from the Yankees back in 1977 who emerged as a regular in 1982 and as a star - .306/.373/.515 with 27 HR and 104 RBI - in 1983. He was first Blue Jay to score 100 runs in a season and the first to drive in as many as well. But his game slowly declined from that point, a little more each year, until he was just the guy blocking McGriff and Fielder from playing time. Adam Lind had a better run here. As I'm sure you all remember, Adam was a weird player. He had two outstanding years with the bat, posting an OPS+ better than 140 - in one of those seasons he hit 35 HRs and in the other he hit 6. He was a complete klutz with a glove on his hand, no matter where you put him, but he always gave a good effort.

27. You're all pretty familiar with Vladimir Guerrero Jr - we often seem to spend much of our time these days discussing him and his game. He's the Mitch Marner of the Blue Jays. So I'll change the subject. Guerrero this year has begun, cautiously and tentatively, using English when speaking to reporters - at least to ones he knows to be friendly, like Hazel Mae. Previously he had always chosen to speak through an interpreter, as has become the custom for many modern players. And I just want to say - I don't blame them. Not one little bit. No one ever wants to sound stupid, and almost no one sounds smart speaking a second language that you don't normally use in everyday life. Players also don't want to make a mistake, and say something that creates a problem. And they're taught to believe that a good chunk of the media is looking to create problems, to stir up trouble - and they're not wrong. It used to sell newspapers, it does whatever it does these days. The media used to grumble about Joe Carter; they appreciated that he was always professional and accommodating; but Joe was also a cliche machine, a guy who had all the Bull Durham lessons tattooed on his soul. They very much preferred someone like George Bell, a man who had no filter whatsoever. George's mouth did create a few problems, for himself and the team, which always seemed a strange way to repay him for his candour.

28. People were angry at Al Leiter for leaving town as a free agent after 1995 for years - make that decades - afterwards. Not me, but helping a team win a World Series goes a very long way at my house, and Leiter is one of five men who have won a World Series game for the Blue Jays. He was damaged goods when he arrived, and it took years for him to fight his way back onto the field - there were a couple of setbacks - but he would eventually demonstrate just why he was such a hyped prospect as a young Yankee, and why the Blue Jays were willing to give up Jesse Barfield to get him. He was a big southpaw with a powerful fastball who spent his entire career fighting his control (save for those years when Mike Piazza was his catcher.).

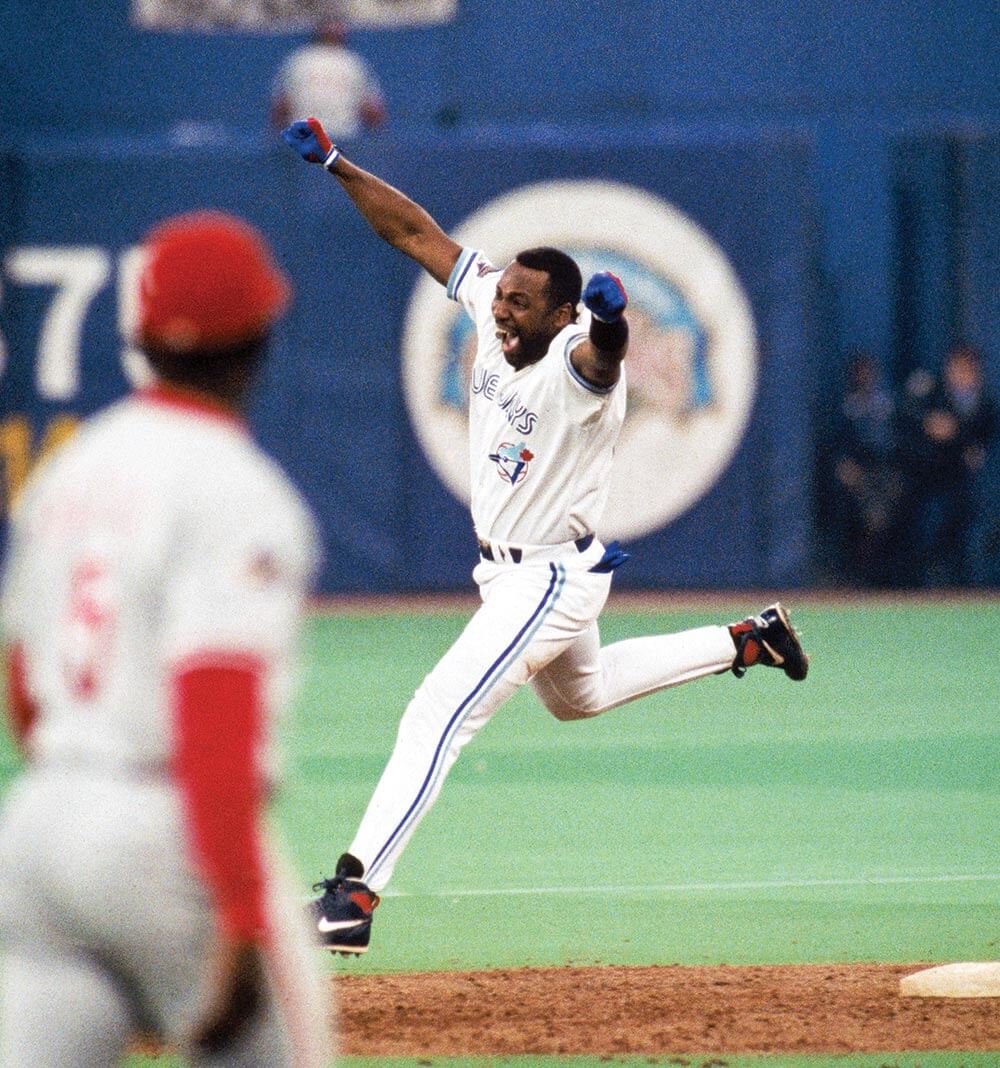

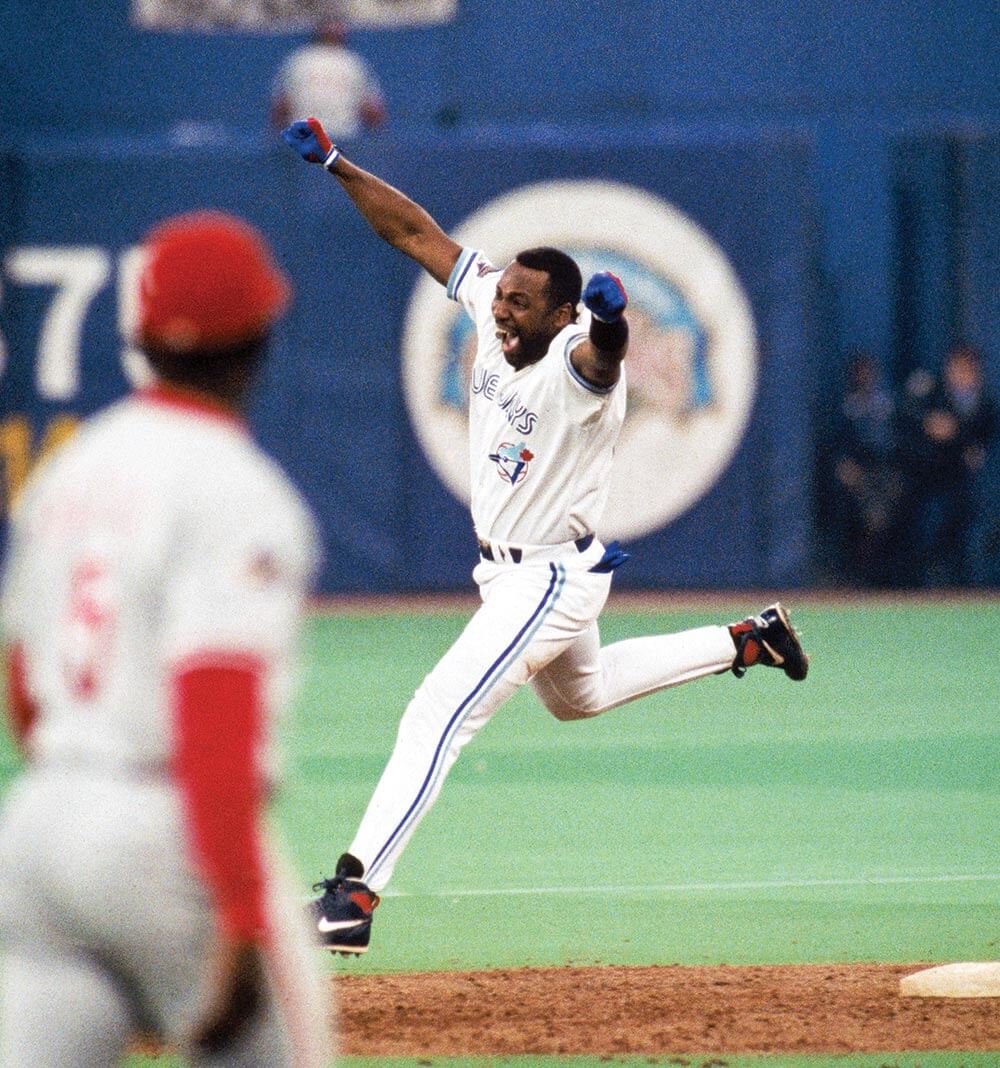

29. I know. The best Blue Jay to wear this number was Jesse Barfield - he was the best hitter and definitely the best defender. It took Barfield three years to break out of the platoon and secure the everyday job, and after two outstanding seasons, his game began to slip. Jesse played 512 games at the old Ex and his career ended at age 32. I don't know if Jesse Barfield had the best outfield arm ever, but I do know this - no outfielder in the last 100 years erased enemy baserunners at a higher clip. None of them. Not even Clemente. And if that's not what an outfield arm is for, someone needs to explain it to me. I know, I know, I know. But Joe Carter was at the centre of the two most iconic moments in franchise history, he hit one of the biggest home runs in the history of baseball... and Joe could play a little, too.

30. Carter wore this number in Cleveland and Devon White wore it for the Angels. But when they came to Toronto, it was being worn by Todd Stottlemyre. This was the number Todd's father Mel wore during his fine career as a Yankee pitcher. Todd wasn't quite as good as his dad, but he did win 138 games over 14 MLB seasons. He actually had his best years after leaving Toronto, but he was a rotation starter on both championship teams and provided some brilliant work out of the bullpen in the 1992 post-season. His World Series start a year later, and his baserunning misadventure that same evening - well, let's not dwell on that.

31. Dave Winfield had worn this number for almost 20 years, in San Diego, New York, and California but it wasn't available in Toronto. No, not because of Jim Acker - Acker had been traded to Atlanta in 1986 and the guy who came back in exchange was still around, a sweaty right-hander with a filthy undershirt and an even filthier two-pitch arsenal -a nasty fastball and a curve he threw so hard that AL hitters to a man thought it was a slider. It all ended suddenly for Duane Ward - those pitches he threw in the 9th inning of the final game of the 1993 World Series were the last pitches he ever threw as himself - that had to be some imposter who tried to come back two years later. But for three years, 1991-93, he was about as good a pitcher as you could hope to see.

32. So this is what Dave Winfield settled for when he couldn't get number 31. In 1992, he became the first 40 year old to drive in 100 runs in a season, exactly as Bill James had predicted almost ten years before in the 1983 Baseball Abstract. He also exorcised some old personal demons (Mr May!) that went back to the 1981 World Series (1-22) by driving in the Series winning runs. Good times indeed, but you know where we're going here. It's just unbearably sad that Roy Halladay is no longer with us. The drugs he was taking when he died - an antidepressant, an opioid, a muscle relaxant - suggests to me that his athletic career might have left him with some chronic pain. Still, he seemed to be in a good place, to be a happy man. Far too young to be gone.