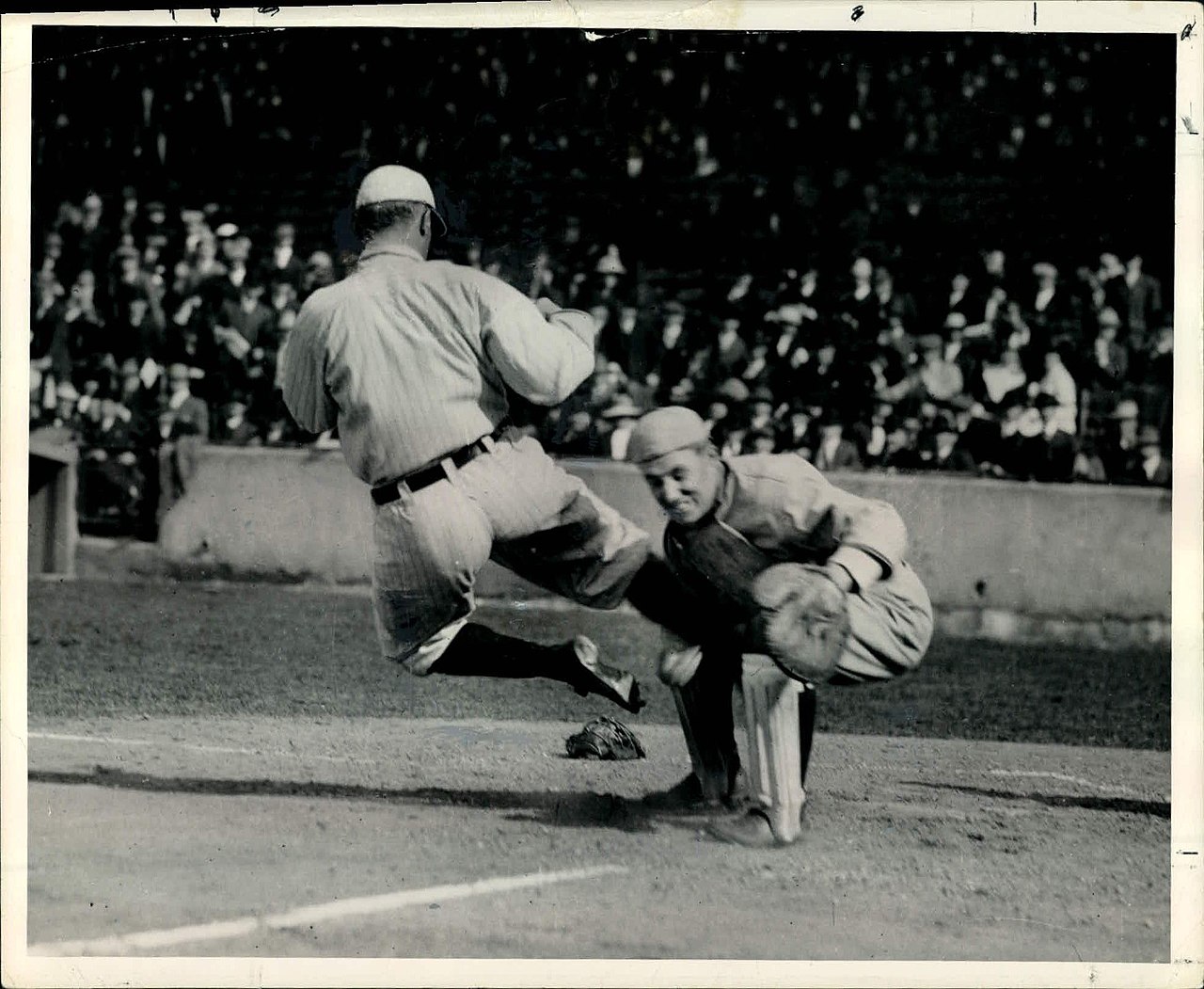

Here's a famous photograph. (Yes, it's some windy baseball lore, for a day with no baseball.)

It fits so nicely with the legend of Ty Cobb, does it not? The man who would do anything, however vicious and underhanded, merely to gain the next base. He'd probably sharpened his spikes before hand.

He hadn't. Cobb didn't actually sharpen his spikes, the better to maim poor unsuspecting infielders. That was merely one of the scary stories the other players liked to tell about him, possibly to frighten the rookies, and Cobb was happy to let them think it might be true.

The St. Louis Browns' catcher seen here attempting to make the tag was Paul Krichell, who would become one of the game's legendary figures himself. That had to wait until his playing days were over, but Krichell became one of the most remarkable scouts the game would ever see. He worked for the Yankees and what did he do for them? He signed Lou Gehrig, for starters. And that was just the beginning. Over the years, he would discover Leo Durocher, Tony Lazzeri, Charlie Keller, Johnny Murphy, Hank Borowy, Phil Rizzuto, and Whitey Ford for the Yankees. He tried but was unable to sign Hank Greenberg, who didn't like his chances of playing for the Yankees (Lou Gehrig was already there.) Ed Barrow, one of the greatest general managers in the game's history, said Krichell was the best judge of baseball players he ever saw. Far more than most scouts of his time, Krichell was very much interested in a prospect's character and intelligence. He figured anyone could tell whether some young fellow could hit or run or throw. But did this particular prospect have the emotional and intellectual makeup required to succeed in the majors? Krichell always wanted to know the answer to that question. He had a strong preference for college players, simply because he thought they were likely to be smarter and more mature.

Krichell spent most of his fifteen year playing career in the minor leagues - he made stops in both Montreal and Toronto along the way - but in 1911 and 1912 he made it to the majors as the backup catcher for the Browns. This game must have been played in 1912 - Krichell appeared in just two games against the Tigers in 1911, but Cobb didn't play in either. Of the many times Detroit played St. Louis in 1912, there were just two games that season when Cobb stole a base while Krichell was doing the catching for the Browns, a 9-3 Tigers win in July and a 4-2 Browns win in September. Both games were played at Navin Field in Detroit.

He hadn't. Cobb didn't actually sharpen his spikes, the better to maim poor unsuspecting infielders. That was merely one of the scary stories the other players liked to tell about him, possibly to frighten the rookies, and Cobb was happy to let them think it might be true.

The St. Louis Browns' catcher seen here attempting to make the tag was Paul Krichell, who would become one of the game's legendary figures himself. That had to wait until his playing days were over, but Krichell became one of the most remarkable scouts the game would ever see. He worked for the Yankees and what did he do for them? He signed Lou Gehrig, for starters. And that was just the beginning. Over the years, he would discover Leo Durocher, Tony Lazzeri, Charlie Keller, Johnny Murphy, Hank Borowy, Phil Rizzuto, and Whitey Ford for the Yankees. He tried but was unable to sign Hank Greenberg, who didn't like his chances of playing for the Yankees (Lou Gehrig was already there.) Ed Barrow, one of the greatest general managers in the game's history, said Krichell was the best judge of baseball players he ever saw. Far more than most scouts of his time, Krichell was very much interested in a prospect's character and intelligence. He figured anyone could tell whether some young fellow could hit or run or throw. But did this particular prospect have the emotional and intellectual makeup required to succeed in the majors? Krichell always wanted to know the answer to that question. He had a strong preference for college players, simply because he thought they were likely to be smarter and more mature.

Krichell spent most of his fifteen year playing career in the minor leagues - he made stops in both Montreal and Toronto along the way - but in 1911 and 1912 he made it to the majors as the backup catcher for the Browns. This game must have been played in 1912 - Krichell appeared in just two games against the Tigers in 1911, but Cobb didn't play in either. Of the many times Detroit played St. Louis in 1912, there were just two games that season when Cobb stole a base while Krichell was doing the catching for the Browns, a 9-3 Tigers win in July and a 4-2 Browns win in September. Both games were played at Navin Field in Detroit.

As it happened, Krichell remembered the play quite clearly. Cobb wasn't attempting to bring an end to any hopes Krichell might have of one day siring children. Cobb was deliberately kicking the ball out of Krichell's glove. This would have been far easier in 1912 than it would become after the advent of the modern, hinged catcher's mitt. Krichell was wearing what was essentially a large, stiff, round oven mitt.

Anyway, it worked. Krichell couldn't hold the ball, which flew to the backstop. You can see it in the photo, that blurry round object right by Krichell's backside. The Georgia Peach scored the run, which was pretty much all he ever cared about. Krichell blamed himself:

it was really my fault. I was standing in front of the plate, instead of on the side, where I could tag Ty as he slid in. But out of that mix-up I learned one thing: never stand directly in front of the plate when Cobb was roaring for home.

it was really my fault. I was standing in front of the plate, instead of on the side, where I could tag Ty as he slid in. But out of that mix-up I learned one thing: never stand directly in front of the plate when Cobb was roaring for home.