The tale of the White Sox started out well, but soon went right into the dumpster. Where it stayed for a very long time.

It was a hundred years ago. Everyone involved has been dead for a long time. Most of them, in fact, were already dead when Eliot Asinof did the first serious research on the scandal, in 1963's Eight Men Out. Alas, Asinof's work combines historical research with flights of fancy that go beyond speculation and venture into the realms of fiction. It's pretty clear that an effort was made to cover up what had happened. Documents disappeared, confessions were recanted. There is a general consensus that the White Sox started out trying to throw the series, and accordingly lost four of the first five games. They then found themselves being double-crossed by the gamblers who had organized the fix, and attempted to double-cross the double-crossers. They won the next two games, but Lefty Williams (0-3, 6.61 in the Series) managed to lose the final game pretty much all by himself.

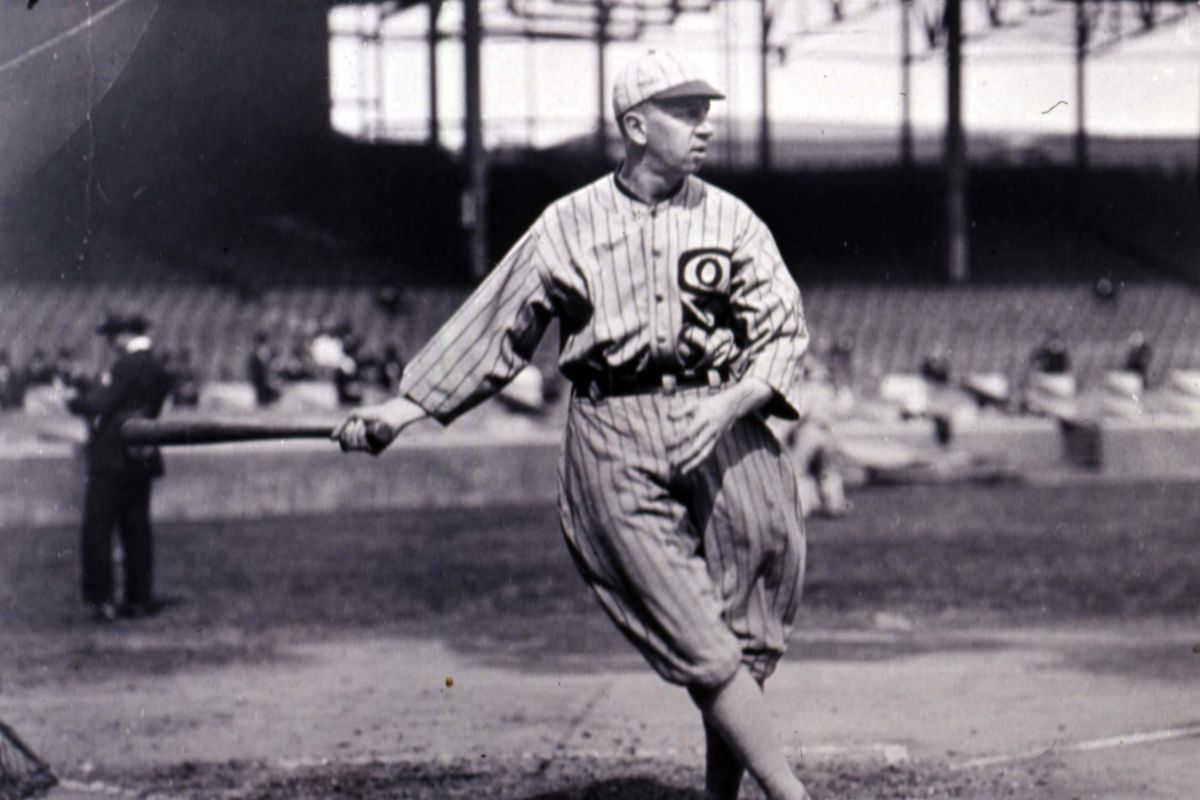

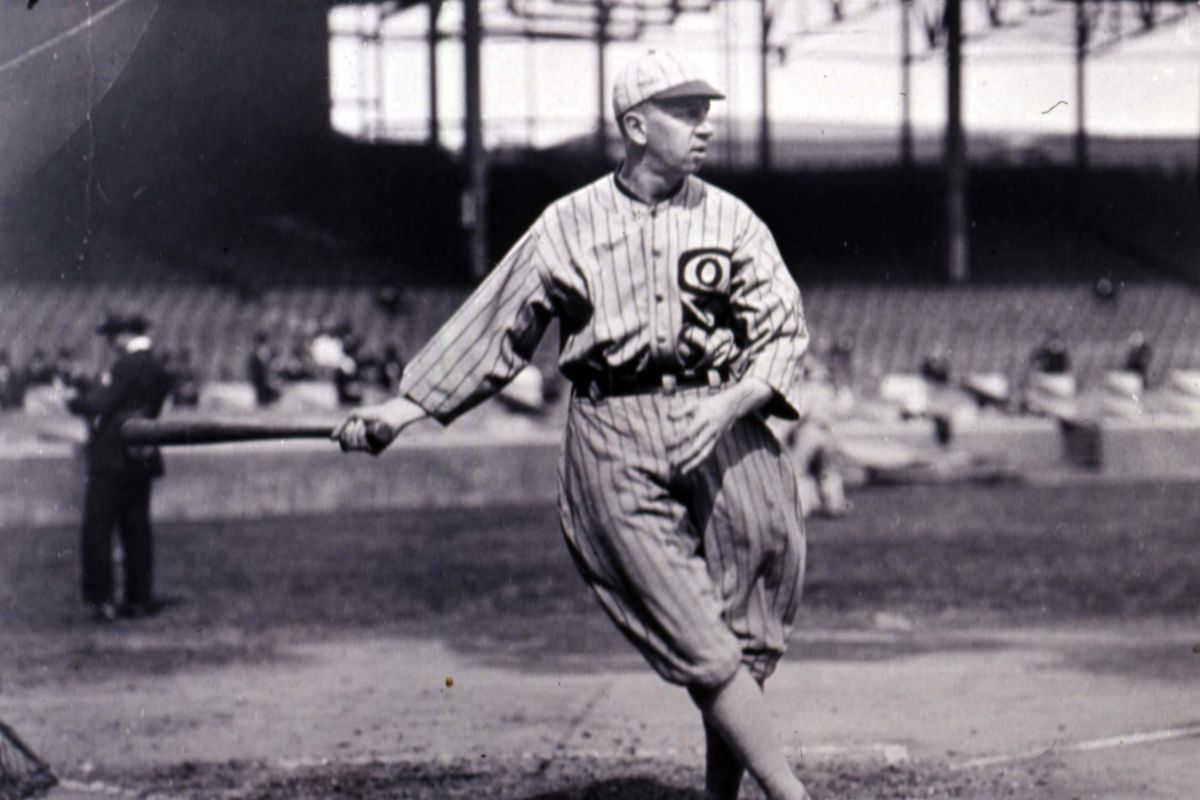

Some of the players involved admitted their guilt. It was ace pitcher Eddie Cicotte's confession that broke the story wide open. First baseman Chick Gandil was acknowledged to be the ringleader. The play of Williams and shortstop Swede Risberg spoke for itself. Happy Felsch said he was willing to mess up but simply didn't have the opportunity. Felsch did play badly enough in centre field to get himself shifted to right field before the series was over, while hitting .192. Third baseman Buck Weaver maintained that he had just sat in on a meeting, and had tried his best anyway. He would spend the rest of his life pleading for reinstatement. Joe Jackson wasn't in on the meetings, but he admitted taking the money. He maintained that he had tried to refuse it, but he ended up putting it in his pocket. He said he still tried his best. It was just a coincidence that he had struggled through the first five games, unable to drive in a run. And maybe it was. Because that happens, too. We'll never know, and we'll certainly never know what kind of pressure he felt himself to be under. Jackson was a self-conscious, insecure man, uncomfortable around many of his own teammates, intimidated by both the fast talking hard men like Gandil and Risberg and the smart-ass college guys like Collins and Schalk. (Isn't it weird that one of the game's greatest stars was intimidated by Swede Risberg, the 25 year old non-hitter who batted .080 in the Series with more errors than hits?)

But yes, everything went to hell. As was right and appropriate. The White Sox had had sixteen winning seasons in their first twenty years and by 27 September 1920, the franchise stood 314 games above .500 (1637-1523), their highest mark ever. To this day. Because the very next day, the eight Black Sox who had fixed the 1919 World Series were suspended, and would eventually be banished from the game forever. And the White Sox collapsed. They would spend almost four decades being lousy. By 1948, the franchise record slipped below .500 for the first time in team history. They reached the deepest point of their abyss, 109 games below .500, on 27 September 1950, exactly thirty years to the day from their high-water mark. Two months later, Joe Jackson died. He was the first of the Black Sox to depart this mortal plane, and with his passing the clouds that had long hung over the House of Comiskey finally began to lift. In 1951, they posted their first winning season since 1943. It would be the first of seventeen straight winning seasons. They could only win one pennant in all that time, and they lost that World Series, but by 1956 the franchise record was back above .500, and they've been able to stay there ever since. The last of the Black Sox, Swede Risberg, died in 1975. It would still take another 30 years for the Sox to finally exorcise all their ghosts and win another World Series.

All this means that the White Sox were generally a crummy team during the first few decades that they had numbers on their backs. So most of the players here will come from the period that begins with the death of Joe Jackson (the Al Lopez years) and continues to the present day.

1. You might remember Lance Johnson, a hotshot outfield prospect that the Cardinals simply didn't have room for. So they traded him to Chicago and he gave the Sox six decent years in centre field. But I think Jim Landis was was a little better - a better hitter, and one of the very best defensive outfielders of his time. Like many others, Landis stopped hitting when the strike zone expanded in the early 1960s.

2. Old Comiskey Park wasn't that bad a park for offense. It was just a terrible place to try to hit home runs. This didn't bother Nellie Fox very much. He never planned on hitting any of them anyway. He was an outstanding second baseman who hit .303 from 1951 through 1960, leading the league in hits four times. He was the 1959 MVP when the White Sox were the only non-Yankees squad to win the AL pennant during the ten seasons that ran from 1955 to 1964. Fox probably wasn't quite as valuable that year as Mantle or Pascual, and it wasn't even his best season, but he was close enough and someone had to get the credit for dethroning the Yankees. Fox spent fifteen years on the Hall of Fame ballot, generally improving his vote totals every year, until his last chance in 1985, only to come up exactly two votes short of induction (74.7% of the vote!) The Veterans Committee eventually put him in. Fox himself was long gone by then; when active he had always been seen with a huge hunk of chewing tobacco in his cheek. I don't know if there's a connection between that habit and the lymphatic cancer that took him at age 47 in 1975.

3. I think it's pretty clear that Harold Baines is going to be the designated representative of players who don't deserve their spot in the Hall of Fame. Like George Kelly, what should have been an honour is actually going to tarnish his reputation going forward. And that just seems so sad to me. Let's not forget that Harold Baines was a really good player. Knee injuries put an end to his days as an outfielder after just seven seasons, and he was obviously not as dangerous a hitter as those other career DHs named Ortiz and Martinez. But you don't have to be that good to be a good player. There was a very simple reason Baines lasted forever - it's because he just kept hitting. Not as well as Ortiz or Martinez, sure, but when he was 40 years old Baines hit .312/.387/.533, which will keep you in anybody's lineup.

5. I think Ray Durham has been forgotten rather quickly. He was a very fine player - not a Gold Glover but good enough defensively and a guy who did a bit of everything with the bat - hit for a decent average, draw some walks, get some extra base hits, steal some bases.

6. Toronto fans will remember Jorge Orta for the season he spent in Toronto as the LH part of a DH platoon, along with Cliff Johnson, during the Jays' first winning season. It's somewhat unusual to see a player who came up as a second baseman, and made an All-Star game, end up as a DH. Let's say he never did have a good defensive reputation. At this rather distant historical remove, it looks as if he had a lot of trouble turning the DP. When Paul Richards replaced Chuck Tanner as the White Sox manager, he immediately inserted career utility man Jack Brohamer at second and used Orta at 3b or lf. But he could always hit, although the Jays had him for one of his very worst seasons.

7. Apologies to Jim Rivera but I think Cass Michaels was a better player. Michaels was just 19 years old when took over as the White Sox shortstop in 1945. He probably wasn't ready, but the Sox DP combination of Don Kolloway and Luke Appling were busy with World War II. Kolloway and Appling returned to the lineup in 1946 and Michaels spent a couple of years backing them up. He took over at short in 1948, with Appling moving to 3b and when Kolloway was traded early in 1949, Michaels replaced him at 2b with Appling (who was 42 years old by now) returning to short. He had his career year that season, hitting .308 while drawing 101 walks. The rest of the team's offense was so tragically inept that he scored just 73 runs. Unluckily for him, Nellie Fox showed up the very next year and Michaels - still just 24 years old - was traded to Washington. After wandering the AL for a few years, he returned to the White Sox in 1954 and took over at 3b. That August, he was hit in the head by a pitch and the ensuing vision problems ended his career at age 28.

8. There was a time when Canadian born major leaguers were extremely uncommon, and while Pete Ward was born in Montreal, the son of an NHL veteran, he actually grew up in Portland. He arrived with a rush, posting two very fine seasons at 3b for the White Sox and finishing second in the Rookie-of-the-Year vote for 1963. But he was not a good defensive player at all. Then he hurt his neck in a car accident. He hurt his back after that, and Don Buford took away his job at third. Ward's bat fell off as he moved around the diamond, and while he was still able to hit with some pop he was playing in one of the worst parks possible for the type of hitter he was.

10. Dave Stieb wore this during his very brief tenure with the White Sox, but our man here is Sherm Lollar, who played twelve seasons in Chicago and was probably the second-best catcher in the league for much of that time. He had brief trials with Cleveland and the Yankees before making it to stay with the St Louis Browns. Lollar was the prize in an eight player deal between the Browns and White Sox before the 1952 season that also saw long-time Jays pitching coach Al Widmar come to Chicago. Lollar was a very good defensive catcher and a dangerous RH batter with some pop.

12. I remember that A.J. Pierzynski irritated me enormously, he was one of those opposing players I had almost a personal grudge against - and I'm damned if I can remember why. Oh well. He was a LH batter with a little pop but one who never took a walk and he was also, as he will acknowledge, a high-maintenance personality. He came up with the Twins, and may have had his best seasons there, but they traded him to the Giants for Joe Nathan and Francisco Liriano. Nicely done! The Giants non-tendered him after a single season, he signed with the White Sox as a free agent, and in his first season there the Sox finally laid to rest the ghosts of 1919 with the first World Series win in 88 years. He took care of the catching duties for another seven seasons.

13. Like Carrasquel and Aparicio, Ozzie Guillen was a shortstop from Venezuela. He was another glove man, who hit singles and didn't walk much. He was a base stealer until suffering a serious knee injury in early 1992 after colliding with Tim Raines in the outfield. He managed to hold the Sox shortstop job for thirteen seasons, despite a .265/.286/.338 batting line and when his playing days were over he returned in 2004 as the Sox manager. He had a pretty decent eight year run, with six winning seasons, two first place finishes, and of course he was at the helm for the 2005 champs. But he quarrelled with his GM and was eventually cut loose. He took over the Marlins in 2012, the year they signed Jose Reyes and Mark Buehrle as free agents. But the team lost 93 games, Ozzie said some things about Fidel Castro that didn't play well in south Florida and the Marlins canned him after a single season. He hasn't managed in the majors since.

14. Two men - Luke Appling and Frank Thomas - hold most of the White Sox career hitting records, and Paul Konerko is usually the next man on the list. He was a first round pick of the Dodgers, with whom he made his ML debut but they quickly traded him to Cincinnati for a relief pitcher. The Reds looked at him for 26 games and sent him on to the White Sox for Mike Cameron. This has to be the more lopsided trades in franchise history. Cameron played well for the Reds but left as a free agent after one season. Konerko spent the next 16 seasons as the White Sox first baseman and hit 432 HRs for them. The number had been worn earlier by the Sox third baseman of the late 1960s, Bill Melton, and we should remember Melton because he was the first Sox player to hit 30 HRs in a season. Melton accomplished that feat in 1970. That's right - 1970. I told you Old Comiskey was a tough place to hit home runs.

15. Melton had hit 33 HRs in 1970 and he did it again in 1971 but he didn't get to hold the team HR record very long. In December 1971 the Sox had traded Tommy John to the Dodgers for Dick Allen, who would be playing for his fourth team in four years. While everyone in the game respected Allen's bat, he brought with him a reputation as a injury-prone troublemaker who was a defensive liability to boot. Much of the former was unfair, when it wasn't actually racist; and his defense might have been better if he'd been allowed to stay at one position. Chicago was the ideal place for him. Chuck Tanner was the most easy-going manager who ever lived; he put Allen at first base and told him to go hit. So that's what he did. In 1972 Allen hit .308/.420/.603 with 37 HRs, 113 RBIs and 99 walks. All those figures except the BAVG led the league, and earned him an MVP award. He was doing exactly the same thing the following year when his season was cut short by a broken leg, and he doing it all yet again when he suddenly quit the team in September of 1974. By then he had already hit enough HRs to end up leading the league. Unsure if he was going to play again, the Sox traded him to Atlanta. Allen immediately announced his retirement - he'd had more than enough of the American South during his minor league days. He would eventually end up playing out the string with two seasons in Philadelphia and one last year in Oakland. That ended when he quit on the A's in June 1977. This story should have turned out better. Dick Allen was as talented a ballplayer as you could ever hope to see. Perhaps in some other time and some other place he would have been able to get the most out of his ability. Allen was a young man of the 60s - in his case, an African-American athlete who, rather than absorb the slights and insults, simply refused to take any crap from anyone. He just wouldn't. This wasn't very good for his career, as it turned out, but what he was able to accomplish was still pretty impressive.

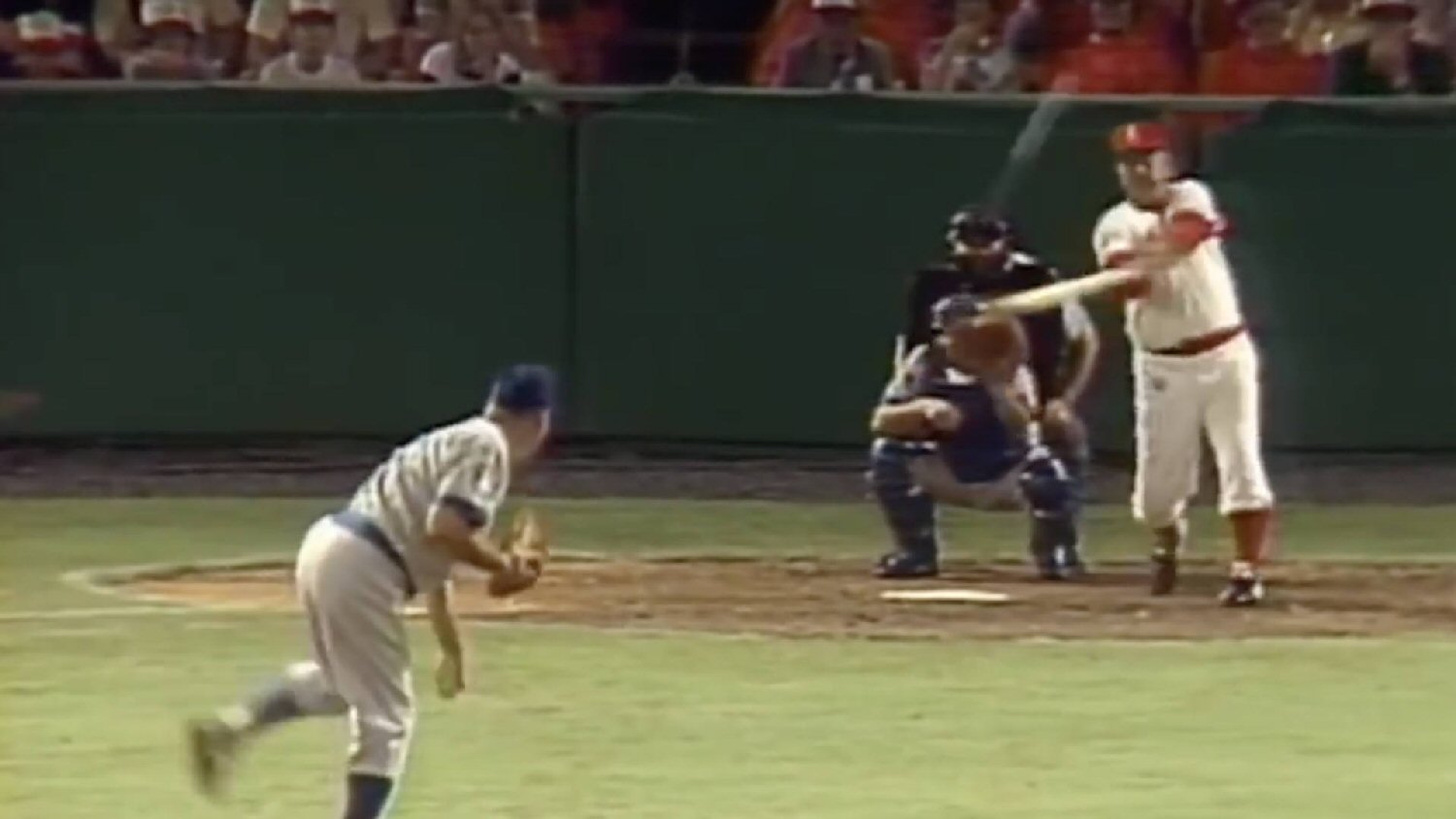

17. This was Chico Carrasquel's number. His name has already come up as the first of the Sox shortstops from Venezuela and Guillen is in fact a pretty good comp for him. Ken Berry was a fine defensive centre fielder who didn't hit all that much - shades of Jim Landis - although he switched to number 16 when Frank Lary came to Chicago. So we'll go with Carlos May, who was a pretty good LH hitter but a truly terrible outfielder. He made it to a couple of All-Star games and played in the 1976 World Series for the Yankees. He went 0-9 as the Yanks were swept by the Reds.

18. I remember Pat Kelly as an Oriole. One day he told Weaver of his decision to devote his life to Jesus. "Earl, I'm going to walk with the Lord." To which Weaver said "I'd rather you walk with the bases loaded." He finished his career as one of Weaver's platooning outfielders, and had some of his most productive years there. But Kelly did spend the heart of his career in Chicago where he made it to one All-Star game. But the most accomplished wearer of this number was surely Red Faber, who spent his entire 20 year career with the White Sox. They only wore numbers at the very end of Faber's time, while he was winning the last of the 254 games he won for the Sox. Only Ted Lyons stands above him on the team's all-time list. Faber was a big right-handed spitballer, and he was one of the few pitchers allowed to keep throwing the pitch once it had been banned after the 1920 season. He was a member of the Black Sox but he was weakened by injury and influenza that year (there was a pandemic, as you probably know) and did not appear in the World Series.

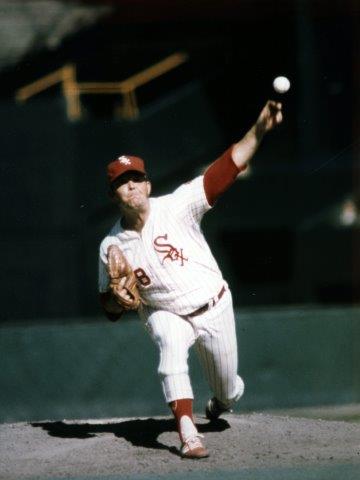

19. The Tigers traded Billy Pierce, at that time a 21 year southpaw with no idea where home plate was located, to the White Sox for a 34 year old catcher who had one good year left in him. Nice work. Pierce was one of those little LH pitchers who throw very, very hard - think Ron Guidry or Billy Wagner - and it took him a couple of years to gain some semblance of control. In his first two Chicago seasons, he walked 249 batters in 391 IP. Even so, he was so hard to hit that he was effective anyway, and once he stopped walking 6 batters every game he was really, really good. He won 186 games in his 13 Chicago seasons, more than any other southpaw in team history, suited up for seven All-Star games, had a pair of 20 win seasons and led the AL in Ks once and ERA once. I think he would have won the AL Cy Young in 1953 and 1955 had the award existed.

20. You may remember Jon Garland, who spent eight seasons in the White Sox rotation, and posted a couple of 18 win seasons. But Joel Horlen was better. Horlen was probably the best pitcher in the AL in 1967 - he went 19-7, 2.06 leading the league in ERA and ERA+ - but Jim Lonborg won 22 games for the Impossible Dream Red Sox and took home the Cy Young (the two votes for Horlen kept it from being unanimous.) Horlen took full advantage of the enormous strike zone that was in effect from 1963-68. During those years, he went 78-63, 2.41. He lost much of his effectiveness when things returned to normal in 1969 (though that was also his age 31 season and most of you know I've got this thing about RH pitchers hitting that time of their careers...)

21. A couple of old pitchers are our best choices here. Old as in it was a long time ago, and old as in they came to Chicago near the end of their careers. Ray Herbert was a 31 year old journeyman with a career record of 49-62 when he went from Kansas City to the White Sox in an eight player deal. Comiskey Park, and a decent team, suited him well - he won 20 games in his first full season in Chicago. One of the men going back to Kansas City in the trade for Herbert was Gerry Staley, who by then was a 40 year old reliever running on fumes. But he was a callow youth of 35 when he arrived in Chicago. He'd been a fine starter for the Cardinals in his youth, but the White Sox turned him into a relief ace and he gave them five outstanding seasons, leading the AL in saves (retrospectively!) in 1959 and putting an ERA+ of 147 in Chicago.

22. The late Ivan Calderon was probably the best baseball player to wear this number for the White Sox. He was murdered in Puerto Rico at age 41. No one knows why and the case is still unsolved. Just a very sad story. Let's not talk about it. After all, we have a genuine Hall of Famer here we can talk about instead. Granted, Dave DeBusschere is in the basketball hall in recognition of his work with those great Knicks teams of the early 1970s. (Yes kids, once upon a time the Knicks had great teams.) But before finding his best, true destiny, DeBusschere spent four years in the White Sox system, one of them with the major league team. He went 3-4, 3.09 and pitched a shutout against Cleveland. But he spent the next two years in AAA and decided to turn his attention to hoops.

23. We have a pair of players here who both gave the White Sox five strong years at one end of their careers. Bob Locker came up with Chicago and immediately became a key part of a strong bullpen, saving 48 games with a 2.68 ERA - whereas Jermaine Dye ended his career with his five seasons in Chicago. They were probably the five best years of a solid career. The Sox had signed him as a free agent to replace Magglio Ordonez in 2005, and in his first year in Chicago Dye hit 31 HR and was the World Series MVP.

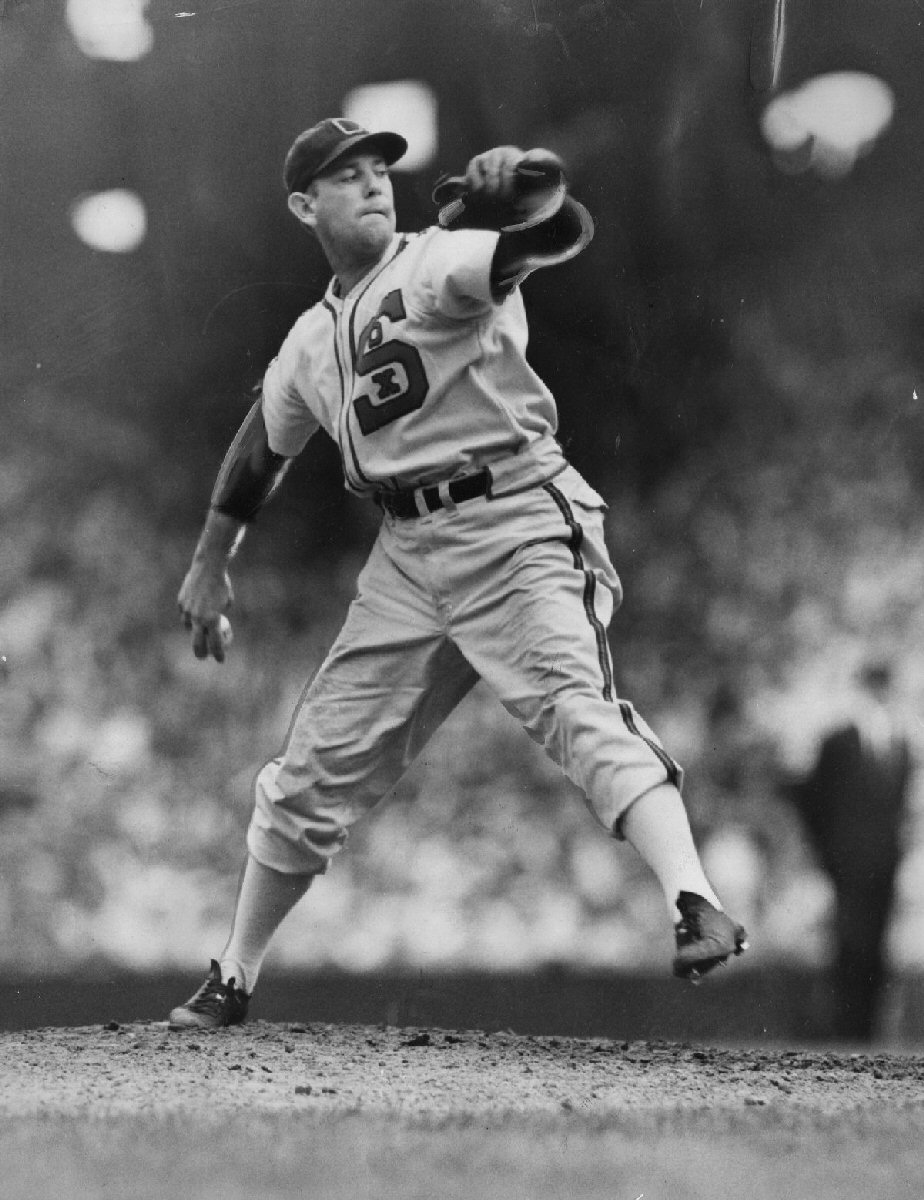

24. White Sox fans were outraged when the team traded Minnie Minoso to Cleveland for Early Wynn. Minoso, of course, was a beloved local icon and while Wynn may have won 20 games four times earlier in the decade, he was now 37 years old. He was also coming off a pretty dismal (14-17, 4.31) season. Sox fans didn't get any happier when Wynn basically repeated that mediocre season in his first year in Chicago. But the old fellow was still throwing hard - he led the AL in KS both years. And in 1959, the old ace got up and walked around the block one more time - he won 22 games and took him the Cy Young award as the Sox won their first pennant since you know when. It was Wynn's last great year. The fastball faded away and he grew more and more reliant on a knuckleball. He finished his Chicago tenure with a 7-15 mark at age 42 which left him with 299 career wins. It was a struggle but he did finally get that last one, by then back with the Indians.

25. Mike Squires was such a brilliant defensive player at first base that the Sox actually played him at third base on several occasions in 1983. What's the big deal? Well, Squires threw left-handed. He was the first southpaw to play at the hot corner in more than fifty years. He also got into one game as a catcher. But Tommy John was obviously a far better player. John became famous as a Dodger, he won more games as a Yankee, but he established himself as a quality major league pitcher in Chicago. He actually started more games and pitched more innings for the White Sox than for anyone else. His teammates over the course of his career included Early Wynn (debuted in 1939) and Al Leiter (retired in 2005) which is pretty awesome if you ask me.

26. For some reason, no one who wears this number stays in Chicago very long - the 26 with the longest tenure is Avisail Garcia. So a one-year wonder is only appropriate. El Duque, the wonderful Orlando Hernandez had been a fine pitcher for the Yankees and an absolute ace in the post-season. But he was (at least) 32 years old when he came out of Cuba and he was (at least) 39 by the time he got to Chicago. And he didn't have a great year for the White Sox, going 9-9, 5.12 in 22 starts. But in the post-season, the Old Master got up and walked around again. The White Sox were up 2 games to nothing against the defending WS champs and took a 4-2 lead into the sixth inning. They were 12 outs away from advancing. But Manny Ramirez led off with a HR against starter Freddy Garcia. LH Damaso Marte came out of the bullpen. He gave up a single to Nixon and then walked Mueller and Olerud to load the bases. With the White Sox clinging to a one-run lead, Ozzie Guillen called for El Duque. And the old man came through. He stranded all three runners on two infield popups and a strikeout and proceeded to cruise through the next two innings as well, allowing just a two out single in the eighth. Bobby Jenks finished up for the Save, but the old man had recorded a Hold for the Ages. Or the Aged. I absolutely loved watching him work. It was always such wonderful entertainment I could almost forgive him for the pinstripes. Almost.

27. When Carlton Fisk came to the White Sox in 1981, he found that the number 27 he'd worn in Boston was being filled by LH Ken Kravec. Kravec had put in three solid seasons in the White Sox rotation before enduring an injury-riddled 1980 campaign. So Fisk just reversed the numbers on his uniform, and stuck with his new number even when the White Sox traded Kravec away at the end of spring training. But let's go with another LH starter, a good pitcher who's completely forgotten today. Thornton Lee was a big man for the 1930s, a hard thrower who couldn't find the strike zone until he was 30 years old. Which happened to be his first season with the White Sox. He spent 11 seasons in Chicago, going 104-104, 3.33 (ERA+ 124) for what was generally a pretty lousy ball club. His best season was 1941, when he went 22-11, 2.37 and led the league in ERA and CGs, and getting my retroactive Cy Young award.

29. I should think Jays fans would have fond memories of Black Jack McDowell, who was a fine pitcher but the Blue Jays absolutely owned his ass. He won 20 games twice, which helped him grab a Cy Young award that probably should have gone to Kevin Appier. He had his last good season at age 30, but he'd already started a second career as a guitar player. Greg Walker, a first baseman with a bit of pop, had this number for a long time and he gave the Sox a couple of solid years as well.

30. Venezuela has been good to the White Sox and it didn't just produce shortstops. Magglio Ordonez took over in RF in 1998 and put together six very fine years, hitting .300 with around 30 HRs and 100 RBIs like clockwork. A knee injury cost him much of the 2004 season and the Sox let him walk as a free agent when Detroit offered him $85 million. His replacement, Jermaine Dye, helped the Sox win a World Series; Ordonez lost much of the same season to a hernia. But he then gave the Tigers three strong seasons before time started to catch up with him. In his final season, at age 37, he finished the season with an 18 game hitting streak the longest ever by a player at the end of his career (he then went 5-13 in the post-season.)

31. LaMarr Hoyt walked off with a Cy Young award in 1983 when he went 24-10 games with a 3.66 ERA; the year before he'd gone 19-15, 3.53. At his best, he was a solid enough innings eater whose great virtue was his stinginess with the walk. After an off-year, he was traded to San Diego where he had a fine bounce back season in 1985. Then he started getting arrested and suspended repeatedly for drugs violations and was out of the game by age 31. Whereas Hoyt Wilhelm almost managed to stick around until he was 50. Wilhelm actually pitched longer for the White Sox than anywhere else, despite not joining them until he was already 40 years old. The old man was simply brilliant coming out of the Sox bullpen, saving 99 games with a 1.92 ERA in his time in Chicago.

32. The Sox chose Alex Fernandez with the fourth overall pick in June 1990 and two months later he was in the Sox rotation, battling major leaguers to a draw. He won 79 games for the White Sox before leaving as a free agent, and after one year in Florida a rotator cuff injury basically ended his career. But I actually like Juan Pizarro just a little better. He was a hard-throwing LH from Puerto Rico, one of a gang of young pitchers lost in a crowd in Milwaukee. They had the big three of Spahn, Burdette, and Buhl - and fighting for opportunity behind them were Pizarro, Joey Jay, Don Nottebart, George Brunet, and Carlton Willey - all of whom would eventually demonstrate that they could indeed pitch in the majors if someone would just give them a chance. Pizarro led the AL in K/9 his first two years in Chicago, going 26-21, 3.44, which was pretty decent. His problem, as always, was that he had trouble throwing strikes. Then, in 1963 the strike zone suddenly got much, much bigger and for two years Pizarro was an All-Star, as he went 35-17, 2.48. Alas, he hurt his shoulder the next season and lost much of the big fastball. He lasted another nine seasons, working mostly in relief, wandering from team to team.

33. This one is going to be painful for Blue Jays fans but Mike Sirotka was a fine pitcher until his arm fell off. It took him a few years to establish himself, but he had three years in the Chicago rotation and each was better than the one before. And then he was done.

34. Richard Dotson appeared in ten seasons for the White Sox, and he switched to this number halfway through his tenure. Freddy Garcia wasn't there nearly as long, but he gave the Sox two of the best years of his long career. Garcia gets special consideration for his work in the 2005 post-season, winning all three of his starts with a 2.14 ERA.

36. In his first World Series game, Jim Kaat beat none other than Sandy Koufax (he hooked up with Koufax twice more in that series and Sandy took the precaution of pitching a CG shutout both times.) Seventeen years later, at age 42, Kaat made four appearances out of Whitey Herzog's bullpen in the 1982 series, which was when he finally earned himself a championship ring. He'd won 283 games in the major leagues by then. That hasn't been enough to get him into the Hall of Fame, which seems to take a dim view of "compilers" these days. I think you have to be pretty damn good to compile 283 wins. As a starter Kaat was usually a pretty good innings eater, but every few years he would elevate himself to being a really good innings eater. He spent 15 of his 25 seasons with the Twins franchise (they were still in Washington when he came up in 1959) but in 1973 Kaat had a bitter contract fight with owner Calvin Griffith. That August, with the Twins in the midst of a losing streak, Griffith put Kaat on waivers. Waivers! The White Sox gleefully snapped him up and in a little more than two seasons Kaat went 45-28, 3.10 for the Pale Hose. Kaat was a remarkably graceful athlete, especially for a man as big as he was and is, and he would win an unprecedented 16 consecutive Gold Gloves. He spent some time as a pitching coach after finally ending his playing career before moving into a long and successful career as a broadcaster. There can't be that many old ballplayers who've won seven Emmy awards.

37. The Save was invented in 1969. The following year Hoyt Wilhelm saved 35 games, which happened to be more than anyone had saved in a season (once people had burrowed through half a century of box scores and figured out what had happened before 1969.) The record remained in the high 30s until the mid 1980s. That was when Dan Quiseberry and Bruce Sutter raised the bar considerably, as both saved 45 games in a season. They were quickly topped by Dave Righetti's 46 in 1986. And there the record stood until Bobby Thigpen of the White Sox, completely out of the blue, saved 57 games in 1990. Thigpen was 26 years old, in his fifth season, and he had actually been a fairly mediocre closer all the while. While he had saved 91 games, he had also seemed to grow less effective every year. But in 1990, he was genuinely brilliant. He returned to normal the following year, grew less and less effective, and was through by the time he was 30.

38. Pickings are pretty slim, but Frank Baumann actually led the AL with a 2.67 ERA in 1960, working as a swingman (47 appearances, 20 starts.)

39. It took a long time for Roberto Hernandez to make it to the major leagues. He moved slowly though the Angels and White Sox systems and was 27 years old by the time he finally made a MLB roster. He wasted no time, immediately establishing himself as a quality closer. He held the job in Chicago for six seasons and only two men have saved more games for the White Sox. He was still pitching in the majors, and pitching very effectively when he was 41 years old.

40. Once upon a time, the White Sox traded their best LH pitcher to the AL East in exchange for a starting pitcher. The pitcher the White Sox received didn't do much for them, but they guy they traded away never did throw another pitch in the majors. Tough luck, pal. You lose. Of course I'm speaking of Britt Burns (what were you thinking?). Burns was just 26 years old, coming off an 18-11 season, when a degenerative hip condition ended his career before he ever could pitch for the Yankees. But Wilson Alvarez was probably just a little bit better, and he arrived in what could have been an even bigger steal of a deal - the Sox traded their 30 year old DH (Harold Baines) and a utility infielder for Alvarez, a useful middle infielder (Scott Fletcher) and a skinny 21 year old outfielder named Sammy Sosa. If only they had been smart enough to keep him as well. They did keep Alvarez, at least, and he gave the Sox a couple of very fine seasons.

41. Yes, it's Tom Seaver. He was 39 when the White Sox stole him away from the befuddled Mets and he was just terrific for Chicago. Of course he was.

42. The 1983 Rookie of the Year was Ron Kittle, who hit 35 HRs and drove in 100 runs while playing left field very, very badly. He was kind of like Rob Deer with even less plate discipline, but Deer was at least an adequate outfielder. Kittle was a born DH with a hole in his swing you could drive a truck through. But he hit enough balls far enough to stick around until he was 33..

43. Comiskey Park during the second dead ball era was a wonderful place to pitch, and Gary Peters led the AL in ERA twice during those years (1963 and 1966) while also posting 19 and 20 win seasons. Oddly enough, the huge strike zone didn't reduce the walks he allowed, but he was very hard to hit. When the strike zone returned to normal, he was a league average innings eater. He was also a pretty decent hitter (for a pitcher), hitting .222 with 19 HRs and 102 RBI and making 77 pinch hit appearances over the years.

44. The White Sox pilfered a 20 year outfielder named Chet Lemon from the Oakland A's in mid 1975 - a year later he was Chicago's starting centre fielder and within a couple more years he was one of the very best players in the American League. From 1978-82 Lemon hit .304/.386/.482 while running down everything in centre field. And I mean everything - in 1977, Lemon set what is still the AL record for putouts by a centre fielder with 509. So what did the Sox do? They traded him away, for Detroit's Steve Kemp. Kemp and Lemon were both 27 years old, both one year away from free agency. They were very close as hitters - but while Kemp was a solid left fielder, Lemon was an outstanding centre fielder. Who signed long-term with Detroit and helped them to a World Series win in 1984. Kemp left Chicago after a single season to sign with the Yankees.

45. The White Sox had sent Stan Bahnsen to the A's in the Lemon deal. Bahnsen had been the 1968 Rookie of the Year after going 17-12, 2.05 for the Yankees. He settled in after that as a durable inning-eater. He came to Chicago just as the White Sox were experimenting with having their starters eat lots of innings. Lots and lots of innings. Bahnsen went 39-37 in his first two years in Chicago - yes, two years - and he lost considerable effectiveness after that, being merely a flesh and blood human and not a bionic device (or a knuckleballer.) He did hang around for years in various bullpens. So we're going to go with Carlos Lee for this number. You should remember him. He was a pretty bad outfielder, but he could really hit. After he hit .305 with 31 HR in 2003 the White Sox traded him for Scott Podsednik, a deal that on its surface made no sense at all. None whatsoever. Naturally Podsednik immediately helped them win a World Series.

46. The 1993 Sox had the AL MVP (Frank Thomas), the Cy Young winner (Jack McDowell), the Manager of the Year (Gene Lamont) - but they had to settle for the Rookie of the Year runner-up. That was Jason Bere, whom they'd selected in the 36th round just three years earlier. He'd shot through the system anyway and made his debut a day after his 22nd birthday. He went 12-5, 3.47 as a rookie and was 12-2 the following year when the strike ended the season. And then his arm started hurting. After an 8-15, 7.19 year he had Tommy John surgery. He came back too soon from that, but managed to hang around as a league average pitcher for a few more years. He finished his playing career in Cleveland, and then spent the next nine years working as a special assistant to Mark Shapiro in the front office. In 2015, he put the uniform back on and spent three years as the Indians' bullpen coach. He was replacing Kevin Cash and working with pitching coach Mickey Callaway. Someone should ask him about it, don't you think?

48. He's best known for his days with the Yankees, but Eddie Lopat came up with the White Sox. He pitched quite well in Chicago for four seasons before being traded to the Yankees for their backup catcher and a couple of nobodies. Lopat was the very model of a soft-tossing lefty. He averaged just 3.2 K/9 (his best figure was 3.9 in 1947.) Stengel famously said of him "Every time he pitches, fans come down out of the stands asking for tryouts."

49. I don't know why Richard Dotson gave up this number - it seems to have happened at some point during his 22 win season in 1983. I dimly remember him as a league average sinkerballer...

50. You probably remember John Danks, a southpaw out of Austin Texas who was drafted by the Rangers in the first round in 2003. He had been sent to Chicago in the Brandon McCarthy deal before he ever pitched for the Rangers. After a rough rookie year with the 2007 White Sox, Danks developed into a solid starter. He had three fine seasons before hurting his arm in 2011. He scuffled for a few more years but never regained his form. But along the way he married Ashley Monroe, part of the wonderful Pistol Annies and a fine artist in her own right. The man gets a backstage pass anytime he wants.

51. You surely remember Alex Rios. The Blue Jays simply got - tired? frustrated? disappointed? - and put him on waivers in August 2009. The White Sox snapped him up, and in 2012 he probably had the best year of his career in Chicago.

52. He's probably regarded as a disappointment, but Jose Contreras definitely had his moments. It was a big deal when he defected from Cuba and signed with the Yankees - but the adjustment was very difficult for him, his performance was inconsistent, and Steinbrenner was Steinbrenner. They traded him to the White Sox, who a year later added Orlando Hernandez to the staff. El Duque was an enormous help to Contreras, in adjusting to the North American game and the North American life - after a so-so start, Contreras finished the year winning his last 8 starts and pitching splendidly in the post-season. He picked up where he left off in 2006, and was 9-0 when the All-Star break came around. And that was it, more or less. He was already 34 years old (at least) and there simply wasn't much left although he hung around for another seven years.

53. You likely remember Dennis Lamp - he came up with the Cubs and spent four years in the rotation before going across town and spending three years as a pretty decent swingman with the White Sox. He saved 15 games in the last of those seasons, so the Blue Jays, desperate for someone to close games, signed him as a free agent. Lamp was a disappointment as a closer, but pitched brilliantly in middle relief (11-0, 3.32) for the 1985 team. And then Jimy Williams took over and it all went to hell.

54. The Goose himself, Rich Gossage, started out with the White Sox and it was there that he established himself as a scary good (and good and scary) relief ace, leading the AL in saves and posting a 1.84 ERA when he was 23 years old. So new manager Paul Richards, an old-fashioned type of fellow, tried to make him into a starter. Gossage went 9-17, which proved he wasn't worthy. So they traded him to the Pirates for Richie Zisk.

55. Well, Carlos Rodon pitched a no-hitter a few weeks ago. He's still got a chance to do more for the Sox than Philip Humber.

Of the strange numbers beyond 55, three players need to singled out. There's our old chum Mark Buehrle (56), who had a no-hitter and a perfect game among his 161 wins for the White Sox; Carlton Fisk (72) had his best years in Boston but played almost 1500 games with the White Sox; and there's the defending AL MVP Jose Abreu (79), who's already fifth in franchise HRs (and he should pass Fisk and Baines later this year.)

They were one of the original AL teams, starting up along with the league in 1901. They were a good team from the beginning. They were the surprise winners of the third World Series in 1906, when the Hitless Wonders of Fielder Jones upset the mighty Cubs. They were generally a middle of the pack team for the next decade, but in 1915 they added two all-time greats to their roster: second baseman Eddie Collins, purchased from the A's when Connie Mack ran into money troubles, and outfielder Joe Jackson, obtained from the Indians for cash and a collection of warm bodies. The 1917 team won their second World Series. 1918 was a lost year, as the war took a number of key players out of the lineup. But they made it back to the World Series in 1919, were heavy favourites to win another title - and lost a best of nine series to the underdogs from Cincinnati. Rumours started up almost immediately that the 1919 games had not been on the level. The scandal broke wide open the following September, with one week left in the season and the White Sox locked in a close fight for the pennant with Cleveland and New York.

Some of the players involved admitted their guilt. It was ace pitcher Eddie Cicotte's confession that broke the story wide open. First baseman Chick Gandil was acknowledged to be the ringleader. The play of Williams and shortstop Swede Risberg spoke for itself. Happy Felsch said he was willing to mess up but simply didn't have the opportunity. Felsch did play badly enough in centre field to get himself shifted to right field before the series was over, while hitting .192. Third baseman Buck Weaver maintained that he had just sat in on a meeting, and had tried his best anyway. He would spend the rest of his life pleading for reinstatement. Joe Jackson wasn't in on the meetings, but he admitted taking the money. He maintained that he had tried to refuse it, but he ended up putting it in his pocket. He said he still tried his best. It was just a coincidence that he had struggled through the first five games, unable to drive in a run. And maybe it was. Because that happens, too. We'll never know, and we'll certainly never know what kind of pressure he felt himself to be under. Jackson was a self-conscious, insecure man, uncomfortable around many of his own teammates, intimidated by both the fast talking hard men like Gandil and Risberg and the smart-ass college guys like Collins and Schalk. (Isn't it weird that one of the game's greatest stars was intimidated by Swede Risberg, the 25 year old non-hitter who batted .080 in the Series with more errors than hits?)

But yes, everything went to hell. As was right and appropriate. The White Sox had had sixteen winning seasons in their first twenty years and by 27 September 1920, the franchise stood 314 games above .500 (1637-1523), their highest mark ever. To this day. Because the very next day, the eight Black Sox who had fixed the 1919 World Series were suspended, and would eventually be banished from the game forever. And the White Sox collapsed. They would spend almost four decades being lousy. By 1948, the franchise record slipped below .500 for the first time in team history. They reached the deepest point of their abyss, 109 games below .500, on 27 September 1950, exactly thirty years to the day from their high-water mark. Two months later, Joe Jackson died. He was the first of the Black Sox to depart this mortal plane, and with his passing the clouds that had long hung over the House of Comiskey finally began to lift. In 1951, they posted their first winning season since 1943. It would be the first of seventeen straight winning seasons. They could only win one pennant in all that time, and they lost that World Series, but by 1956 the franchise record was back above .500, and they've been able to stay there ever since. The last of the Black Sox, Swede Risberg, died in 1975. It would still take another 30 years for the Sox to finally exorcise all their ghosts and win another World Series.

All this means that the White Sox were generally a crummy team during the first few decades that they had numbers on their backs. So most of the players here will come from the period that begins with the death of Joe Jackson (the Al Lopez years) and continues to the present day.

1. You might remember Lance Johnson, a hotshot outfield prospect that the Cardinals simply didn't have room for. So they traded him to Chicago and he gave the Sox six decent years in centre field. But I think Jim Landis was was a little better - a better hitter, and one of the very best defensive outfielders of his time. Like many others, Landis stopped hitting when the strike zone expanded in the early 1960s.

2. Old Comiskey Park wasn't that bad a park for offense. It was just a terrible place to try to hit home runs. This didn't bother Nellie Fox very much. He never planned on hitting any of them anyway. He was an outstanding second baseman who hit .303 from 1951 through 1960, leading the league in hits four times. He was the 1959 MVP when the White Sox were the only non-Yankees squad to win the AL pennant during the ten seasons that ran from 1955 to 1964. Fox probably wasn't quite as valuable that year as Mantle or Pascual, and it wasn't even his best season, but he was close enough and someone had to get the credit for dethroning the Yankees. Fox spent fifteen years on the Hall of Fame ballot, generally improving his vote totals every year, until his last chance in 1985, only to come up exactly two votes short of induction (74.7% of the vote!) The Veterans Committee eventually put him in. Fox himself was long gone by then; when active he had always been seen with a huge hunk of chewing tobacco in his cheek. I don't know if there's a connection between that habit and the lymphatic cancer that took him at age 47 in 1975.

3. I think it's pretty clear that Harold Baines is going to be the designated representative of players who don't deserve their spot in the Hall of Fame. Like George Kelly, what should have been an honour is actually going to tarnish his reputation going forward. And that just seems so sad to me. Let's not forget that Harold Baines was a really good player. Knee injuries put an end to his days as an outfielder after just seven seasons, and he was obviously not as dangerous a hitter as those other career DHs named Ortiz and Martinez. But you don't have to be that good to be a good player. There was a very simple reason Baines lasted forever - it's because he just kept hitting. Not as well as Ortiz or Martinez, sure, but when he was 40 years old Baines hit .312/.387/.533, which will keep you in anybody's lineup.

4. In the twenty seasons that Luke Appling suited up for the White Sox, his team won more games than they lost just five times. It sure wasn't Luke's fault. He made his Chicago debut in 1930 and by the time he retired, in 1950, no one had played more games in the major leagues at shortstop (he's since fallen to eighth on the all-time list.) Appling hit .310 lifetime, drew as many as 122 walks in a season, and had no power whatsoever. You look at that skill set and you think - this guy would have been the best leadoff hitter in the league. But we'll never know - Appling batted leadoff exactly twice in his career, spending most of his time hitting out of the 5 hole. He lost most of two seasons to the war, which kept him short of 3,000 hits, and that may have kept him out of the Hall of Fame for a couple of years. But he was inducted in 1964 and was able to enjoy the honour for almost 30 years. Appling was famous in his own day for two things. He was one the game's great hypochondriacs, to the extent that his nickname was "Old Aches and Pains." And he was notorious for his uncanny ability to foul off pitches at will, one after another, until he got one he wanted to swing at. It drove pitchers absolutely crazy. Appling's day was long ago - yes, even before my time. But I, and perhaps some other older Bauxites, still remember fondly an Old-Timers Game in 1982. A 75 year old Luke Appling led off against 61 year old Warren Spahn and Old Aches and Pains knocked a ball over the fence in left field. The old man jogged happily, and carefully, around the basepaths, with Spahn chasing him in mock-fury every step of the way.

5. I think Ray Durham has been forgotten rather quickly. He was a very fine player - not a Gold Glover but good enough defensively and a guy who did a bit of everything with the bat - hit for a decent average, draw some walks, get some extra base hits, steal some bases.

6. Toronto fans will remember Jorge Orta for the season he spent in Toronto as the LH part of a DH platoon, along with Cliff Johnson, during the Jays' first winning season. It's somewhat unusual to see a player who came up as a second baseman, and made an All-Star game, end up as a DH. Let's say he never did have a good defensive reputation. At this rather distant historical remove, it looks as if he had a lot of trouble turning the DP. When Paul Richards replaced Chuck Tanner as the White Sox manager, he immediately inserted career utility man Jack Brohamer at second and used Orta at 3b or lf. But he could always hit, although the Jays had him for one of his very worst seasons.

7. Apologies to Jim Rivera but I think Cass Michaels was a better player. Michaels was just 19 years old when took over as the White Sox shortstop in 1945. He probably wasn't ready, but the Sox DP combination of Don Kolloway and Luke Appling were busy with World War II. Kolloway and Appling returned to the lineup in 1946 and Michaels spent a couple of years backing them up. He took over at short in 1948, with Appling moving to 3b and when Kolloway was traded early in 1949, Michaels replaced him at 2b with Appling (who was 42 years old by now) returning to short. He had his career year that season, hitting .308 while drawing 101 walks. The rest of the team's offense was so tragically inept that he scored just 73 runs. Unluckily for him, Nellie Fox showed up the very next year and Michaels - still just 24 years old - was traded to Washington. After wandering the AL for a few years, he returned to the White Sox in 1954 and took over at 3b. That August, he was hit in the head by a pitch and the ensuing vision problems ended his career at age 28.

8. There was a time when Canadian born major leaguers were extremely uncommon, and while Pete Ward was born in Montreal, the son of an NHL veteran, he actually grew up in Portland. He arrived with a rush, posting two very fine seasons at 3b for the White Sox and finishing second in the Rookie-of-the-Year vote for 1963. But he was not a good defensive player at all. Then he hurt his neck in a car accident. He hurt his back after that, and Don Buford took away his job at third. Ward's bat fell off as he moved around the diamond, and while he was still able to hit with some pop he was playing in one of the worst parks possible for the type of hitter he was.

9. Hey, here's someone who was really, really good. Cleveland signed Minnie Minoso out of Cuba when he was 23 years old, but he was a third baseman then. Stuck behind Ken Keltner and then Al Rosen, he abused Pacific Coast League pitchers for a couple of years before the Indians gave him a break and traded him to the White Sox, part of a three team deal that landed the Indians a LH reliever named Lou Brissie. Finally in an everyday lineup at age 25, Minoso basically exploded on the league hitting .326, scoring 112 runs and leading the league with 31 SBs. He was one of the better players in the league for the rest of the decade, most of which he spent playing left field. From 1951 through 1961 he hit .305/.395/.471, and all the while he was being one of the most exciting players in the game, one of the few still willing to steal a base or take an extra one. He probably should have won the 1954 MVP award. He stopped hitting at age 35 - that, and his late start are what depressed his counting numbers enough to have kept him out of Cooperstown. But I'd say he belongs.

10. Dave Stieb wore this during his very brief tenure with the White Sox, but our man here is Sherm Lollar, who played twelve seasons in Chicago and was probably the second-best catcher in the league for much of that time. He had brief trials with Cleveland and the Yankees before making it to stay with the St Louis Browns. Lollar was the prize in an eight player deal between the Browns and White Sox before the 1952 season that also saw long-time Jays pitching coach Al Widmar come to Chicago. Lollar was a very good defensive catcher and a dangerous RH batter with some pop.

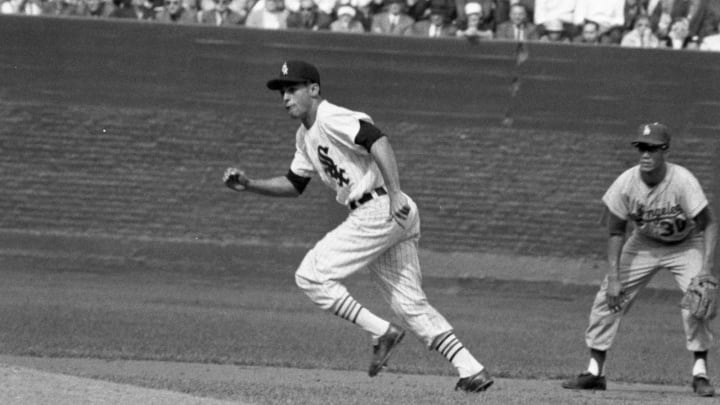

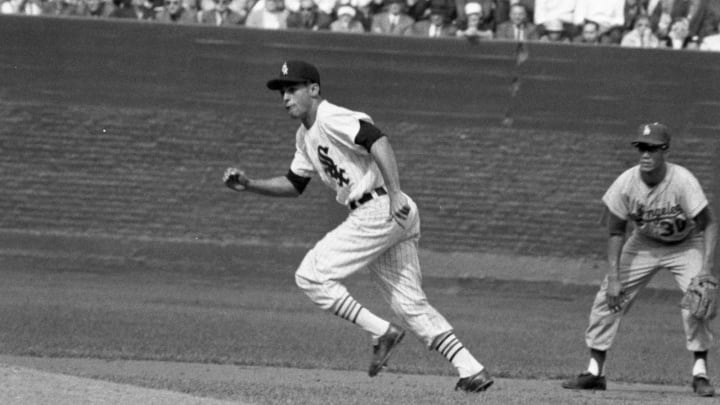

11. In 1950, the White Sox came up with a fine shortstop from Venezuela named Chico Carrasquel, who played in four All-Star games before the Sox traded him away. They did this because they'd found an even better shortstop from Venezuela, one who did everything Carrasquel could do - but better - and who also stole more bases than anyone else had in years. Because Luis Aparicio was a base stealer - he led the league nine times - he spent most of his career batting leadoff, despite his .311 OnBase percentage. But it was his glove that accounted for most of his value anyway - there is certainly a case to be made that he was the greatest defender at short the game had ever seen, until Ozzie Smith came along to complicate things. The Sox had traded Carrasquel when he was turning 29 and they did the same with Aparicio, making a very fine deal with the Orioles that brought back Pete Ward, Ron Hansen, and Hoyt Wilhelm. But Aparicio's game aged remarkably well. He spent five years in Baltimore, winning a couple more Gold Gloves, setting a personal season high in stolen bases, and being part of a World Series winner in 1966. The White Sox brought him back at age 34 for another three seasons before he wrapped his career with the Red Sox. Only two men have played more games at shortstop, and Luis never played even a single inning at any other position. The number's been retired in his honour, as it should be, and Luis scooted into Cooperstown in 1984.

12. I remember that A.J. Pierzynski irritated me enormously, he was one of those opposing players I had almost a personal grudge against - and I'm damned if I can remember why. Oh well. He was a LH batter with a little pop but one who never took a walk and he was also, as he will acknowledge, a high-maintenance personality. He came up with the Twins, and may have had his best seasons there, but they traded him to the Giants for Joe Nathan and Francisco Liriano. Nicely done! The Giants non-tendered him after a single season, he signed with the White Sox as a free agent, and in his first season there the Sox finally laid to rest the ghosts of 1919 with the first World Series win in 88 years. He took care of the catching duties for another seven seasons.

13. Like Carrasquel and Aparicio, Ozzie Guillen was a shortstop from Venezuela. He was another glove man, who hit singles and didn't walk much. He was a base stealer until suffering a serious knee injury in early 1992 after colliding with Tim Raines in the outfield. He managed to hold the Sox shortstop job for thirteen seasons, despite a .265/.286/.338 batting line and when his playing days were over he returned in 2004 as the Sox manager. He had a pretty decent eight year run, with six winning seasons, two first place finishes, and of course he was at the helm for the 2005 champs. But he quarrelled with his GM and was eventually cut loose. He took over the Marlins in 2012, the year they signed Jose Reyes and Mark Buehrle as free agents. But the team lost 93 games, Ozzie said some things about Fidel Castro that didn't play well in south Florida and the Marlins canned him after a single season. He hasn't managed in the majors since.

14. Two men - Luke Appling and Frank Thomas - hold most of the White Sox career hitting records, and Paul Konerko is usually the next man on the list. He was a first round pick of the Dodgers, with whom he made his ML debut but they quickly traded him to Cincinnati for a relief pitcher. The Reds looked at him for 26 games and sent him on to the White Sox for Mike Cameron. This has to be the more lopsided trades in franchise history. Cameron played well for the Reds but left as a free agent after one season. Konerko spent the next 16 seasons as the White Sox first baseman and hit 432 HRs for them. The number had been worn earlier by the Sox third baseman of the late 1960s, Bill Melton, and we should remember Melton because he was the first Sox player to hit 30 HRs in a season. Melton accomplished that feat in 1970. That's right - 1970. I told you Old Comiskey was a tough place to hit home runs.

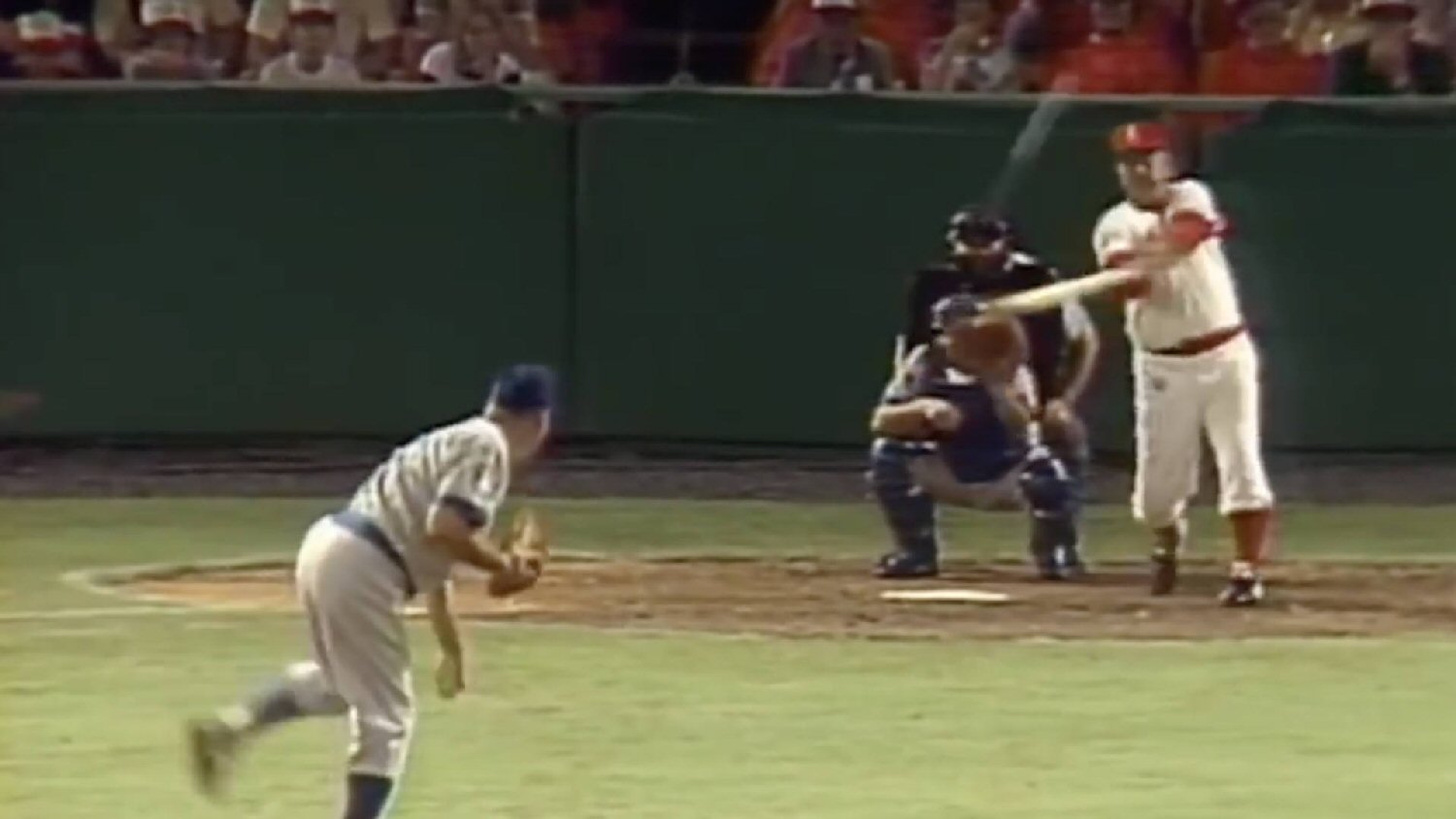

15. Melton had hit 33 HRs in 1970 and he did it again in 1971 but he didn't get to hold the team HR record very long. In December 1971 the Sox had traded Tommy John to the Dodgers for Dick Allen, who would be playing for his fourth team in four years. While everyone in the game respected Allen's bat, he brought with him a reputation as a injury-prone troublemaker who was a defensive liability to boot. Much of the former was unfair, when it wasn't actually racist; and his defense might have been better if he'd been allowed to stay at one position. Chicago was the ideal place for him. Chuck Tanner was the most easy-going manager who ever lived; he put Allen at first base and told him to go hit. So that's what he did. In 1972 Allen hit .308/.420/.603 with 37 HRs, 113 RBIs and 99 walks. All those figures except the BAVG led the league, and earned him an MVP award. He was doing exactly the same thing the following year when his season was cut short by a broken leg, and he doing it all yet again when he suddenly quit the team in September of 1974. By then he had already hit enough HRs to end up leading the league. Unsure if he was going to play again, the Sox traded him to Atlanta. Allen immediately announced his retirement - he'd had more than enough of the American South during his minor league days. He would eventually end up playing out the string with two seasons in Philadelphia and one last year in Oakland. That ended when he quit on the A's in June 1977. This story should have turned out better. Dick Allen was as talented a ballplayer as you could ever hope to see. Perhaps in some other time and some other place he would have been able to get the most out of his ability. Allen was a young man of the 60s - in his case, an African-American athlete who, rather than absorb the slights and insults, simply refused to take any crap from anyone. He just wouldn't. This wasn't very good for his career, as it turned out, but what he was able to accomplish was still pretty impressive.

16. The man who has won the most games in Sox history was Ted Lyons, who pitched in 21 seasons for Chicago. It was usually a pretty terrible team - they generally only had a fighting chance on the days when Lyons was pitching. He was something of a workhorse when he was younger, leading the league twice in CGs and IP, winning more than 20 games three times. But he might be best remembered for his final years as a Sunday pitcher. Lyons was very popular with the Chicago fans, but he was also getting old. So manager Jimmie Dykes took him to starting him once a week and Lyons absolutely thrived - in his final four seasons, after turning 38 years old, he went 52-30, 2.96 with an ERA+ of 143. Who knows how long he could have kept it up - instead he enlisted in the Marines and fought in the Pacific War. When he came back in 1946, he was 45 years old. He made 5 starts, and while he won just once, he completed them all and posted a 2.32 ERA. Lyons is the only pitcher in the Hall of Fame who walked more men than he struck out - but his prime was the 1930s when hitters simply didn't strike out. Joe McCarthy said he would have won 400 games if he'd pitched for the Yankees. That's one of those exaggerations baseball men can't resist, but he surely would have made a good run at winning 300. And I'm giving him the retroactive Cy Young award in 1927.

17. This was Chico Carrasquel's number. His name has already come up as the first of the Sox shortstops from Venezuela and Guillen is in fact a pretty good comp for him. Ken Berry was a fine defensive centre fielder who didn't hit all that much - shades of Jim Landis - although he switched to number 16 when Frank Lary came to Chicago. So we'll go with Carlos May, who was a pretty good LH hitter but a truly terrible outfielder. He made it to a couple of All-Star games and played in the 1976 World Series for the Yankees. He went 0-9 as the Yanks were swept by the Reds.

18. I remember Pat Kelly as an Oriole. One day he told Weaver of his decision to devote his life to Jesus. "Earl, I'm going to walk with the Lord." To which Weaver said "I'd rather you walk with the bases loaded." He finished his career as one of Weaver's platooning outfielders, and had some of his most productive years there. But Kelly did spend the heart of his career in Chicago where he made it to one All-Star game. But the most accomplished wearer of this number was surely Red Faber, who spent his entire 20 year career with the White Sox. They only wore numbers at the very end of Faber's time, while he was winning the last of the 254 games he won for the Sox. Only Ted Lyons stands above him on the team's all-time list. Faber was a big right-handed spitballer, and he was one of the few pitchers allowed to keep throwing the pitch once it had been banned after the 1920 season. He was a member of the Black Sox but he was weakened by injury and influenza that year (there was a pandemic, as you probably know) and did not appear in the World Series.

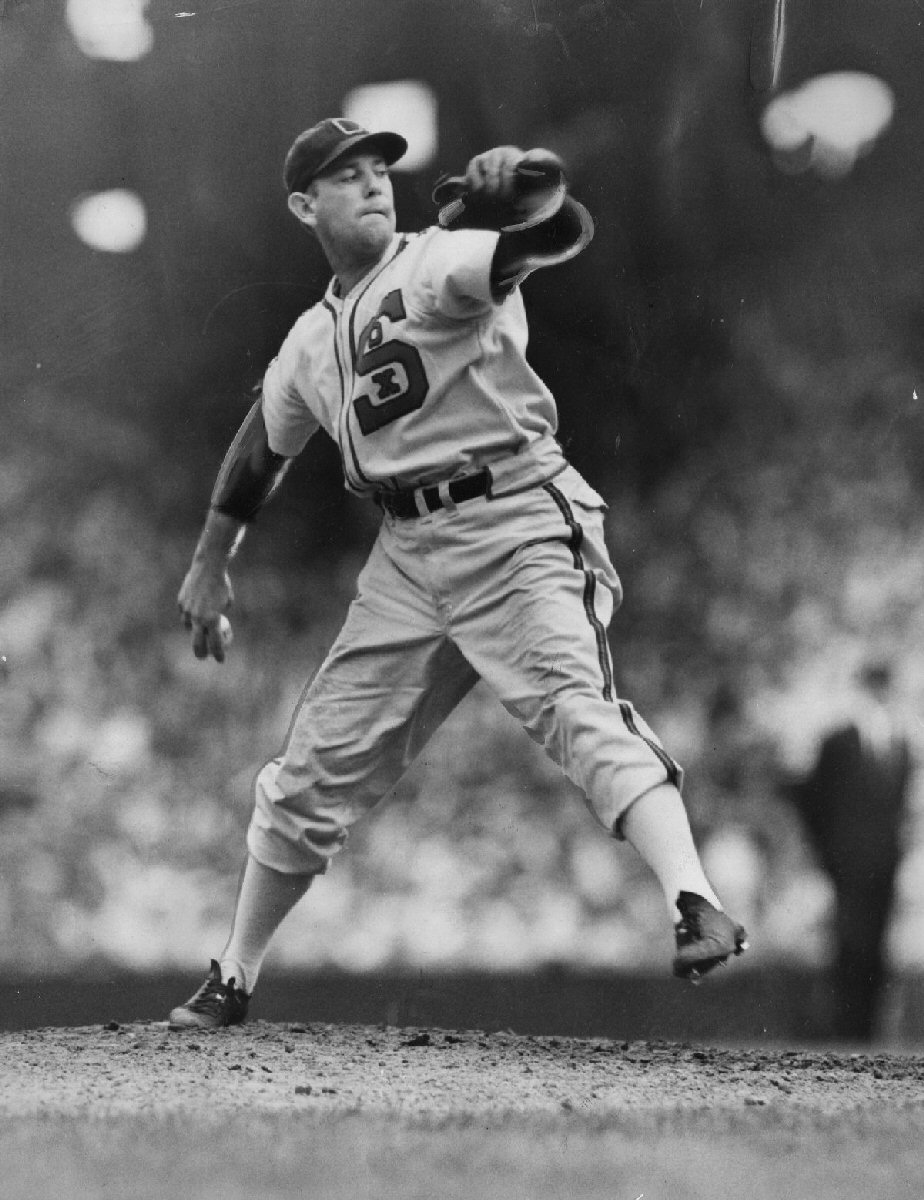

19. The Tigers traded Billy Pierce, at that time a 21 year southpaw with no idea where home plate was located, to the White Sox for a 34 year old catcher who had one good year left in him. Nice work. Pierce was one of those little LH pitchers who throw very, very hard - think Ron Guidry or Billy Wagner - and it took him a couple of years to gain some semblance of control. In his first two Chicago seasons, he walked 249 batters in 391 IP. Even so, he was so hard to hit that he was effective anyway, and once he stopped walking 6 batters every game he was really, really good. He won 186 games in his 13 Chicago seasons, more than any other southpaw in team history, suited up for seven All-Star games, had a pair of 20 win seasons and led the AL in Ks once and ERA once. I think he would have won the AL Cy Young in 1953 and 1955 had the award existed.

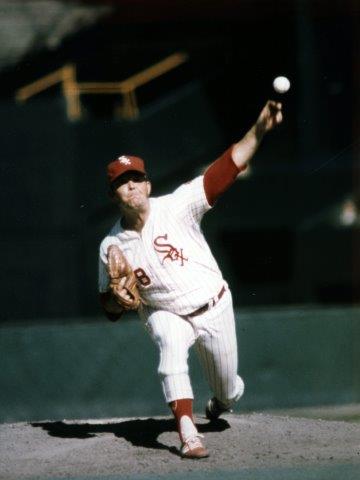

20. You may remember Jon Garland, who spent eight seasons in the White Sox rotation, and posted a couple of 18 win seasons. But Joel Horlen was better. Horlen was probably the best pitcher in the AL in 1967 - he went 19-7, 2.06 leading the league in ERA and ERA+ - but Jim Lonborg won 22 games for the Impossible Dream Red Sox and took home the Cy Young (the two votes for Horlen kept it from being unanimous.) Horlen took full advantage of the enormous strike zone that was in effect from 1963-68. During those years, he went 78-63, 2.41. He lost much of his effectiveness when things returned to normal in 1969 (though that was also his age 31 season and most of you know I've got this thing about RH pitchers hitting that time of their careers...)

21. A couple of old pitchers are our best choices here. Old as in it was a long time ago, and old as in they came to Chicago near the end of their careers. Ray Herbert was a 31 year old journeyman with a career record of 49-62 when he went from Kansas City to the White Sox in an eight player deal. Comiskey Park, and a decent team, suited him well - he won 20 games in his first full season in Chicago. One of the men going back to Kansas City in the trade for Herbert was Gerry Staley, who by then was a 40 year old reliever running on fumes. But he was a callow youth of 35 when he arrived in Chicago. He'd been a fine starter for the Cardinals in his youth, but the White Sox turned him into a relief ace and he gave them five outstanding seasons, leading the AL in saves (retrospectively!) in 1959 and putting an ERA+ of 147 in Chicago.

22. The late Ivan Calderon was probably the best baseball player to wear this number for the White Sox. He was murdered in Puerto Rico at age 41. No one knows why and the case is still unsolved. Just a very sad story. Let's not talk about it. After all, we have a genuine Hall of Famer here we can talk about instead. Granted, Dave DeBusschere is in the basketball hall in recognition of his work with those great Knicks teams of the early 1970s. (Yes kids, once upon a time the Knicks had great teams.) But before finding his best, true destiny, DeBusschere spent four years in the White Sox system, one of them with the major league team. He went 3-4, 3.09 and pitched a shutout against Cleveland. But he spent the next two years in AAA and decided to turn his attention to hoops.

23. We have a pair of players here who both gave the White Sox five strong years at one end of their careers. Bob Locker came up with Chicago and immediately became a key part of a strong bullpen, saving 48 games with a 2.68 ERA - whereas Jermaine Dye ended his career with his five seasons in Chicago. They were probably the five best years of a solid career. The Sox had signed him as a free agent to replace Magglio Ordonez in 2005, and in his first year in Chicago Dye hit 31 HR and was the World Series MVP.

24. White Sox fans were outraged when the team traded Minnie Minoso to Cleveland for Early Wynn. Minoso, of course, was a beloved local icon and while Wynn may have won 20 games four times earlier in the decade, he was now 37 years old. He was also coming off a pretty dismal (14-17, 4.31) season. Sox fans didn't get any happier when Wynn basically repeated that mediocre season in his first year in Chicago. But the old fellow was still throwing hard - he led the AL in KS both years. And in 1959, the old ace got up and walked around the block one more time - he won 22 games and took him the Cy Young award as the Sox won their first pennant since you know when. It was Wynn's last great year. The fastball faded away and he grew more and more reliant on a knuckleball. He finished his Chicago tenure with a 7-15 mark at age 42 which left him with 299 career wins. It was a struggle but he did finally get that last one, by then back with the Indians.

25. Mike Squires was such a brilliant defensive player at first base that the Sox actually played him at third base on several occasions in 1983. What's the big deal? Well, Squires threw left-handed. He was the first southpaw to play at the hot corner in more than fifty years. He also got into one game as a catcher. But Tommy John was obviously a far better player. John became famous as a Dodger, he won more games as a Yankee, but he established himself as a quality major league pitcher in Chicago. He actually started more games and pitched more innings for the White Sox than for anyone else. His teammates over the course of his career included Early Wynn (debuted in 1939) and Al Leiter (retired in 2005) which is pretty awesome if you ask me.

26. For some reason, no one who wears this number stays in Chicago very long - the 26 with the longest tenure is Avisail Garcia. So a one-year wonder is only appropriate. El Duque, the wonderful Orlando Hernandez had been a fine pitcher for the Yankees and an absolute ace in the post-season. But he was (at least) 32 years old when he came out of Cuba and he was (at least) 39 by the time he got to Chicago. And he didn't have a great year for the White Sox, going 9-9, 5.12 in 22 starts. But in the post-season, the Old Master got up and walked around again. The White Sox were up 2 games to nothing against the defending WS champs and took a 4-2 lead into the sixth inning. They were 12 outs away from advancing. But Manny Ramirez led off with a HR against starter Freddy Garcia. LH Damaso Marte came out of the bullpen. He gave up a single to Nixon and then walked Mueller and Olerud to load the bases. With the White Sox clinging to a one-run lead, Ozzie Guillen called for El Duque. And the old man came through. He stranded all three runners on two infield popups and a strikeout and proceeded to cruise through the next two innings as well, allowing just a two out single in the eighth. Bobby Jenks finished up for the Save, but the old man had recorded a Hold for the Ages. Or the Aged. I absolutely loved watching him work. It was always such wonderful entertainment I could almost forgive him for the pinstripes. Almost.

27. When Carlton Fisk came to the White Sox in 1981, he found that the number 27 he'd worn in Boston was being filled by LH Ken Kravec. Kravec had put in three solid seasons in the White Sox rotation before enduring an injury-riddled 1980 campaign. So Fisk just reversed the numbers on his uniform, and stuck with his new number even when the White Sox traded Kravec away at the end of spring training. But let's go with another LH starter, a good pitcher who's completely forgotten today. Thornton Lee was a big man for the 1930s, a hard thrower who couldn't find the strike zone until he was 30 years old. Which happened to be his first season with the White Sox. He spent 11 seasons in Chicago, going 104-104, 3.33 (ERA+ 124) for what was generally a pretty lousy ball club. His best season was 1941, when he went 22-11, 2.37 and led the league in ERA and CGs, and getting my retroactive Cy Young award.

28. The Sox obtained Eddie Fisher - not the singer - in the deal that sent Billy Pierce to the Giants. It didn't seem like much but in 1963 the Sox added Hoyt Wilhelm to their bullpen. Wilhelm taught Fisher his knuckleball and the two of them gave the White Sox a tremendous bullpen combination for the next few years. Five years later Fisher had been traded to the Orioles and Wilhelm had been lost in the expansion draft. But the White Sox had yet another knuckleballer, this one a southpaw. Wilbur Wood had been a hot prospect but failed to stick in multiple trials with the Red Sox and Pirates. By 1967, he was in the Sox system where he encountered... Hoyt Wilhelm. Who taught him that pitch. Wood posted a 2.45 ERA in his first season in the Chicago pen, and the following year he established a new major league record by appearing in 88 games. He went 13-12, 1.87 with 16 saves. He led the league in appearances in each of the next two years as well. After Wood's four fine years in the pen, new manager Chuck Tanner and pitching coach Johnny Sain wanted to try Wood as a starter - and seeing as how Wood threw a knuckleball, Sain thought he could pitch much more often than most pitchers. And he was right. Wood won 20 games four times in the next five seasons, starting at least 42 games and pitching at least 291 innings each year. In 1972, Wood made 49 starts, the most by any pitcher since Big Ed Walsh in 1908. He started 22 games on three days rest, 25 games on two days rest, and worked 376.2 IP (the most since Pete Alexander in 1916). He also led the league with 24 wins. He carried a similar load in 1973, starting 48 games and winning another 24. Over those five seasons, Wood averaged 45 starts, 336 IP, and 21 wins. How long he might have carried on like this we'll never know because it all came to an end in May 1976 when a line drive off the bat of Ron LeFlore shattered his left kneecap. He missed the rest of the season and was never the same again.

29. I should think Jays fans would have fond memories of Black Jack McDowell, who was a fine pitcher but the Blue Jays absolutely owned his ass. He won 20 games twice, which helped him grab a Cy Young award that probably should have gone to Kevin Appier. He had his last good season at age 30, but he'd already started a second career as a guitar player. Greg Walker, a first baseman with a bit of pop, had this number for a long time and he gave the Sox a couple of solid years as well.

30. Venezuela has been good to the White Sox and it didn't just produce shortstops. Magglio Ordonez took over in RF in 1998 and put together six very fine years, hitting .300 with around 30 HRs and 100 RBIs like clockwork. A knee injury cost him much of the 2004 season and the Sox let him walk as a free agent when Detroit offered him $85 million. His replacement, Jermaine Dye, helped the Sox win a World Series; Ordonez lost much of the same season to a hernia. But he then gave the Tigers three strong seasons before time started to catch up with him. In his final season, at age 37, he finished the season with an 18 game hitting streak the longest ever by a player at the end of his career (he then went 5-13 in the post-season.)

31. LaMarr Hoyt walked off with a Cy Young award in 1983 when he went 24-10 games with a 3.66 ERA; the year before he'd gone 19-15, 3.53. At his best, he was a solid enough innings eater whose great virtue was his stinginess with the walk. After an off-year, he was traded to San Diego where he had a fine bounce back season in 1985. Then he started getting arrested and suspended repeatedly for drugs violations and was out of the game by age 31. Whereas Hoyt Wilhelm almost managed to stick around until he was 50. Wilhelm actually pitched longer for the White Sox than anywhere else, despite not joining them until he was already 40 years old. The old man was simply brilliant coming out of the Sox bullpen, saving 99 games with a 1.92 ERA in his time in Chicago.

32. The Sox chose Alex Fernandez with the fourth overall pick in June 1990 and two months later he was in the Sox rotation, battling major leaguers to a draw. He won 79 games for the White Sox before leaving as a free agent, and after one year in Florida a rotator cuff injury basically ended his career. But I actually like Juan Pizarro just a little better. He was a hard-throwing LH from Puerto Rico, one of a gang of young pitchers lost in a crowd in Milwaukee. They had the big three of Spahn, Burdette, and Buhl - and fighting for opportunity behind them were Pizarro, Joey Jay, Don Nottebart, George Brunet, and Carlton Willey - all of whom would eventually demonstrate that they could indeed pitch in the majors if someone would just give them a chance. Pizarro led the AL in K/9 his first two years in Chicago, going 26-21, 3.44, which was pretty decent. His problem, as always, was that he had trouble throwing strikes. Then, in 1963 the strike zone suddenly got much, much bigger and for two years Pizarro was an All-Star, as he went 35-17, 2.48. Alas, he hurt his shoulder the next season and lost much of the big fastball. He lasted another nine seasons, working mostly in relief, wandering from team to team.

33. This one is going to be painful for Blue Jays fans but Mike Sirotka was a fine pitcher until his arm fell off. It took him a few years to establish himself, but he had three years in the Chicago rotation and each was better than the one before. And then he was done.

34. Richard Dotson appeared in ten seasons for the White Sox, and he switched to this number halfway through his tenure. Freddy Garcia wasn't there nearly as long, but he gave the Sox two of the best years of his long career. Garcia gets special consideration for his work in the 2005 post-season, winning all three of his starts with a 2.14 ERA.

35. The Big Hurt. He was the greatest hitter in White Sox history, and one of the greatest RH batters who ever lived. Frank Thomas was an absolutely devastating offensive force, as close to Ted Williams as any right handed batter has ever been. The Sox chose him seventh overall in 1989; barely a year later he was in the major league lineup. He hit .330/.454/.529 in his first taste of major league action, and didn't let up for another ten years. Thomas was an enormous man, standing 6'5 and weighing 240 when he was young and skinny. He was never exactly fat but he had a huge, wide frame and he got quite a bit heavier as he got older and filled out. Eventually the lower part of his body simply began to break down from carrying all that weight around. He had no defensive value at all, even when he was still a first baseman and he was mainly a DH by the time he was 30. But my gosh - what a hitter he was. It was just deflating to see him step into the box. One felt there was so little hope of recording an out anytime soon. How would that even happen? Over his first 11 seasons Thomas hit .321/.440/.579 with 344 HRs, and won back-to-back MVP awards in 1993-94. This was during the steroid era, of course, but Thomas himself was noteworthy as a loud, outspoken advocate for drug testing as early as 1995. He holds basically every Chicago hitting record that matters, and of course he ambled into the Hall of Fame on his first opportunity. Some very big hurts were administered along the way. I'm still frightened.

36. In his first World Series game, Jim Kaat beat none other than Sandy Koufax (he hooked up with Koufax twice more in that series and Sandy took the precaution of pitching a CG shutout both times.) Seventeen years later, at age 42, Kaat made four appearances out of Whitey Herzog's bullpen in the 1982 series, which was when he finally earned himself a championship ring. He'd won 283 games in the major leagues by then. That hasn't been enough to get him into the Hall of Fame, which seems to take a dim view of "compilers" these days. I think you have to be pretty damn good to compile 283 wins. As a starter Kaat was usually a pretty good innings eater, but every few years he would elevate himself to being a really good innings eater. He spent 15 of his 25 seasons with the Twins franchise (they were still in Washington when he came up in 1959) but in 1973 Kaat had a bitter contract fight with owner Calvin Griffith. That August, with the Twins in the midst of a losing streak, Griffith put Kaat on waivers. Waivers! The White Sox gleefully snapped him up and in a little more than two seasons Kaat went 45-28, 3.10 for the Pale Hose. Kaat was a remarkably graceful athlete, especially for a man as big as he was and is, and he would win an unprecedented 16 consecutive Gold Gloves. He spent some time as a pitching coach after finally ending his playing career before moving into a long and successful career as a broadcaster. There can't be that many old ballplayers who've won seven Emmy awards.

37. The Save was invented in 1969. The following year Hoyt Wilhelm saved 35 games, which happened to be more than anyone had saved in a season (once people had burrowed through half a century of box scores and figured out what had happened before 1969.) The record remained in the high 30s until the mid 1980s. That was when Dan Quiseberry and Bruce Sutter raised the bar considerably, as both saved 45 games in a season. They were quickly topped by Dave Righetti's 46 in 1986. And there the record stood until Bobby Thigpen of the White Sox, completely out of the blue, saved 57 games in 1990. Thigpen was 26 years old, in his fifth season, and he had actually been a fairly mediocre closer all the while. While he had saved 91 games, he had also seemed to grow less effective every year. But in 1990, he was genuinely brilliant. He returned to normal the following year, grew less and less effective, and was through by the time he was 30.

38. Pickings are pretty slim, but Frank Baumann actually led the AL with a 2.67 ERA in 1960, working as a swingman (47 appearances, 20 starts.)

39. It took a long time for Roberto Hernandez to make it to the major leagues. He moved slowly though the Angels and White Sox systems and was 27 years old by the time he finally made a MLB roster. He wasted no time, immediately establishing himself as a quality closer. He held the job in Chicago for six seasons and only two men have saved more games for the White Sox. He was still pitching in the majors, and pitching very effectively when he was 41 years old.