It's been a long time since I did one of these, but the incomparable baseball-reference.com has

eliminated much of the heavy lifting that used to be required. (It used

to take hours just to discover who'd worn each number for a

given team.) I've skipped the San Diego Padres (wouldn't you?) - just thinking about the Padres sapped my enthusiasm, my energy, my very will to live - and proceeded straight to The Saga of the Giants! Some Windy Baseball Lore, for a day with no baseball.

The Giants have won more games than any other franchise. It's only partially because they've had a head start on most of the other teams. The National League started up in 1876 with eight teams, only two of which are still with us today: the Chicago White Stockings (now known as the Cubs) and the Boston Red Stockings (who, after numerous name changes, have been known as the Braves for the last hundred years or so, and now operate out of Atlanta.) In those wild and woolly early days, teams joined and left the league with dizzying regularity. By 1882, the NL no longer had a team in New York City, which does seem like an oversight. They did have one in upstate New York, the Troy Trojans. But the Trojans were disbanded after the 1882 because of poor attendance. Half their players ended up on the new NL team established in New York City. They were known as the Gothams at first. But in 1885, Jim Mutrie came over from the American Association, where he'd been managing the New York Metropolitans, bringing some of his best ball players with him. Shortly thereafter, the New York team picked up the nickname that they've carried now for some 130 years. The origin of "Giants" is somewhat lost in the Mists of Time, but it seems to have had something to do with the sheer size of some of the players and the quality of their play. They played better than .650 ball over the next five years and won a couple of league championships.

Mutrie lost control of the team in 1891, in the wake of the first great player-management war. The Giants' best players all jumped to the new Players' League. Mutrie, just 40 years old, left baseball and never came back. No less than eleven different men would manage the Giants over the next decade, including a couple of the game's original great stars (Buck Ewing and Cap Anson.) In 1902, however, they found a keeper. John McGraw had been the third baseman for the outstanding Baltimore teams that had battled with Boston for NL supremacy during the 1890s. Baltimore was one of the team's eliminated when the National League contracted down to eight teams after the 1899 season. Western League president Ban Johnson seized that opportunity to turn his league into a new major league. It was called the American League, and it started play in 1901. They put a new franchise in Baltimore for McGraw, only 29 years old, to operate. But one of Ban Johnson's priorities, visionary that he was, included cleaning up the game. McGraw and his Orioles were notorious for their dirty play - they were the Broad Street Bullies of baseball, and their antics also included outright intimidation of umpires. Johnson wanted to eliminate the rowdies and the hooligans who he believed were driving the fans away. This put him and McGraw on a collision course and midway through his second year in Baltimore, McGraw simply abandoned ship - he and some of his best players left Baltimore, jumping to the NL Giants. Just to irritate Johnson, McGraw brought the Orioles black and orange colours with him to his new team, and of course the Giants wear those colours to this very day.

John McGraw was a giant in every sense of the word but one (he stood 5-7), one of the towering figures in the old game's history. He would run the team for the next 30 years. His Giants were league champs in 1904, but McGraw - still furious with Ban Johnson - refused to play the AL champs in a post-season series. Which is why 1904 is the other season with no World Series. From the day in July 1902, when he took over the team, to when he unexpectedly walked away from the game in June 1932, McGraw's Giants won nine pennants and three championships. Connie Mack, who owned and managed the A's for half a century is the only manager to win more games than McGraw. By eerie coincidence, 1932 was also the year the Giants began wearing numbers on their uniforms, and that's where we come in.

We should not expect to see too many New York Giants here. They remained a powerful franchise through the 1930s, but fell on hard times in the next decade. They had a brief burst of glory early in the 1950s, but by 1956 they were stuck in what used to be called the second division. And their attendance had bottomed out. Sure, the Polo Grounds was now an ancient dump in an unattractive neighbourhood. But in New York City, featuring one of the greatest and most exciting baseball players who ever lived, the Giants were averaging roughly 9,000 spectators per game. It's hard to blame Horace Stoneham for lighting out for the coast. The Giants have been in San Francisco for almost 60 years now, so we should expect to see more of the west coast players below. But it's not where we begin...

8. The Giants team that Bill Terry inherited from McGraw went on to finish sixth in 1932, and Terry's priority for the upcoming season was to improve their run prevention, second worst in the NL. To that end, he made two trades: he brought in light hitting defensive whiz Blondy Ryan to play shortstop in place of the gimpy Travis Jackson, and he obtained Gus Mancuso to replace Shanty Hogan behind the plate. It's always nice when things work exactly as planned. The Giants allowed the fewest runs in the league in 1933, and won the pennant and the World Series in Terry's first year as a manager. Hal Schumacher and Freddie Fitzsimmons both shaved almost 1.5 runs from their ERAs. Even the great Carl Hubbell was helped; he went from 181-11, 2.50 to 23-12, 1.66 with Mancuso receiving much of the credit.

9. The Giants selected Matt Williams out of UNLV with the third pick of the 1986 draft. The following April, having never played a game above A ball, he was their Opening day shortstop. He wasn't ready, and he wouldn't be ready for a couple more years. He made it to stay in the second half of 1989; taking over at third base after his July recall, he batted just .218 but he bashed 16 HRs in just 63 games and added another in the World Series. Over the next five years, Williams was essentially Mike Schmidt-lite: a great glove at third, with lots of HRs and lots of of strikeouts, lacking only Schmidt's tremendous plate discipline. Still a helluva player. In his first full season, he slugged 33 HRs and drove in 122; the year after that he won the first of his six Gold Gloves. In 1994, he was threatening to take a run at the single season HR record (he'd hit 43 in 114 games) when the strike ended the season. After a couple of injury-troubled seasons, the Giants traded him to Cleveland in the Jeff Kent deal. Williams homered in the 1997 World Series for the Indians, who then traded him to Arizona, where he finished his career. He had a couple more big seasons with the D'Backs, and homered in another World Series, this time for a winner. I believe that makes Williams the only man to hit a World Series home run for three different teams.

10. The first man of note to wear this number was Harry Gumbert, a middle of the rotation guy for New York in the late 1930s; since then it's mostly been the property of light-hitting shortstops like Buddy Kerr, Johnnie LeMaster and Royce Clayton. So let's salute a pioneer. In 1964, the Nankai Hawks of the Japanese Pacific League sent a very young LH reliever named Masanori Murakami to San Francisco's A ball affiliate, as a kind of exchange program. They then neglected to call him home in June as originally planned. This suited the Giants just fine - Murakami was far too good for the California League, where he'd posted a 1.78 ERA while striking out 159 batters in 106 innings. So the Giants brought him to the majors when the rosters expanded and on September 1, 1964 he became the first Japanese born player to appear in a major league game. Even if it was against the Mets. Murakami pitched very well that month, well enough to set off an international dispute. The Giants wanted to keep him, the Hawks wanted him back. It was eventually agreed that he'd spend one more year in North America, and then return home. He gave the Giants one more season (having switched his number to 37), and went home to pitch for another 17 years in the JPPL.

11. In 1926, the Detroit Tigers purchased the contract of a lanky left-hander named Carl Hubbell. But once the Tigers had Hubbell in their system, they decided they didn't like him all that much. In particular they didn't like his reliance on the screwball. Ty Cobb believed it damaged pitchers arms and Hubbell was ordered not to throw it. Hubbell did not fare particularly well without his best pitch, and was ready to give up baseball unless he could get free of the Detroit organization. Happily, he did. Detroit sold Hubbell's contract to Beaumont in the Texas League, which is where he was seen, using his screwball again, by a Giants scout named Dick Kinsella. He liked what he saw and told John McGraw about him. McGraw wasn't worried about the screwball; McGraw had watched Christy Mathewson dominate the National League for almost fifteen years with the same pitch. In July, the Giants purchased Hubbell's contract, put him in their starting rotation, which is where he stayed for the next sixteen years. He had a dazzling five year peak from 1933 through 1937, winning at least 21 games each season and walking off with two NL MVP awards. Even so, he's probably best remembered for his performance in an exhibition game. In the 1934 All-Star game, played before Hubbell's hometown fans at the Polo Grounds, Hubbell struck out Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmie Foxx to end the first inning, and opened the second by fanning Al Simmons and Joe Cronin. By the time he retired, he had won more games than any left-hander in NL history.

12. A "tweener" is a basketball concept - a player who's not quick enough to play small forward, not big enough to match up with power forwards. The baseball equivalent is an infielder whose glove isn't quite good enough to play second base, but doesn't have as much bat as you want from your third baseman. That's what Jim Davenport was, although his glove at third was good enough that the Giants generally decided they could live with his bat. He spent his entire playing career with the Giants, and worked for the organization in all kinds of capacities for more than 30 years after he was done playing - major league coach, minor league manager, scout, instructor. They gave him a shot at managing the big league team in 1985. It did not go well - the team was 56-88 when he replaced by Roger Craig, and that 1985 team is the only Giants team to lose 100 games. The only one!

13. Most notable here are a couple of infielders on the downside of their careers, Edgardo Alfonzo and Omar Vizquel, who actually won two Gold Gloves during his tenure with the Giants. The idea that Vizquel, at age 39, was a better player at shortstop than Adam Everett or Rafael Furcal is utter lunacy, of course.

14. When Jesus Alou, younger brother of Felipe and Matty, joined the Giants in September 1963, broadcasters around America didn't know what to do. They simply couldn't call him by his name. They didn't know to pronounce it, and they wouldn't say "Jesus" because that would have been blasphemy or something. Seriously. So they called him "Jay Alou." If the Alous were the DiMaggios at a much lower level, Jesus was Vince. Unlike the DiMaggios, they all came up with the same organization. They never did start together in the outfield (the Giants already had a pretty good centre fielder) and Felipe was traded to the Braves after the 1963 season, Matty to the Pirates after the 1965 season. But the Giants' game on September 15 1963 concluded with Jesus in LF, Felipe in CF, and Matty in RF. Pretty cool.

15. The Big Cat, Johnny Mize, gave the Giants a couple of sensational seasons - in 1947 he became the only man in history to hit more then 50 home runs while striking out less than 50 times - but Johnny Mize was a Cardinal. And he didn't get along with Leo Durocher, so the Giants essentially donated him to the Yankees midway through the 1949 season. As if the Yankees needed the help. So let's acknowledge a future Hall of Famer walking the diamonds of America right now. Every manager with three World Series titles is in the Hall of Fame - that's the magic number. Bruce Bochy now stands 16th on the list of games won by a manager, and he'll go by Jim Leyland this year. He's been at it for 22 years, but at age 61 he could easily carry on for another five years or so. In which case he should easily clear 2000 wins (only 10 managers have as many, and they're all in the Hall.)

John McGraw was a giant in every sense of the word but one (he stood 5-7), one of the towering figures in the old game's history. He would run the team for the next 30 years. His Giants were league champs in 1904, but McGraw - still furious with Ban Johnson - refused to play the AL champs in a post-season series. Which is why 1904 is the other season with no World Series. From the day in July 1902, when he took over the team, to when he unexpectedly walked away from the game in June 1932, McGraw's Giants won nine pennants and three championships. Connie Mack, who owned and managed the A's for half a century is the only manager to win more games than McGraw. By eerie coincidence, 1932 was also the year the Giants began wearing numbers on their uniforms, and that's where we come in.

We should not expect to see too many New York Giants here. They remained a powerful franchise through the 1930s, but fell on hard times in the next decade. They had a brief burst of glory early in the 1950s, but by 1956 they were stuck in what used to be called the second division. And their attendance had bottomed out. Sure, the Polo Grounds was now an ancient dump in an unattractive neighbourhood. But in New York City, featuring one of the greatest and most exciting baseball players who ever lived, the Giants were averaging roughly 9,000 spectators per game. It's hard to blame Horace Stoneham for lighting out for the coast. The Giants have been in San Francisco for almost 60 years now, so we should expect to see more of the west coast players below. But it's not where we begin...

1. The Giants, like their Bronx rivals across the Harlem River, originally assigned uniforms numbers according to a player's spot in the batting order. That's why Babe Ruth wore #3. The Giants' lead-off hitter and left-fielder through the 1930s was Jo-Jo Moore, who played in six All-Star Games and scored more than 100 runs three times.

2. "Nice Guys Finish Last" is what Leo Durocher said about the New York Giants under Mel Ott's management. Durocher was managing the Dodgers at the time, but Leo and Branch Rickey was not exactly a partnership built to last. Durocher was suspended for the 1947 season for "associating with known gamblers" (it apparently involved a rigged craps game.) The Dodgers won the pennant without him, and while Durocher returned to the dugout in 1948, by then Rickey had had quite enough of Leo and his wild ways. In mid-season 1948, Rickey and Horace Stoneham worked out a deal to have Durocher take over from Ott as the Giants' manager. This worked out well for everyone. The Dodgers continued to win (pennants in 1949, 1952, and 1953) and Durocher quickly had the Giants back in contention. They triumphed over the Dodgers in the famous three game playoff in 1951, only to lose to the Yankees in the World Series. But in 1954 they swept the Cleveland Indians to win the team's first championship since 1933. Durocher in his time was a very different kind of manager. He was not a father figure, not a role model. Off the field, he liked to drink, curse, chase women, bet on horses, wear expensive suits, and hang with movie stars. On the field, he liked to scream at people - both umpires and his own players. His very concept of managing largely involved intimidating his own players (and he did this almost entirely with veteran players.) Durocher was the orignal scrappy middle infielder as baseball manager, and many like him came in his wake.

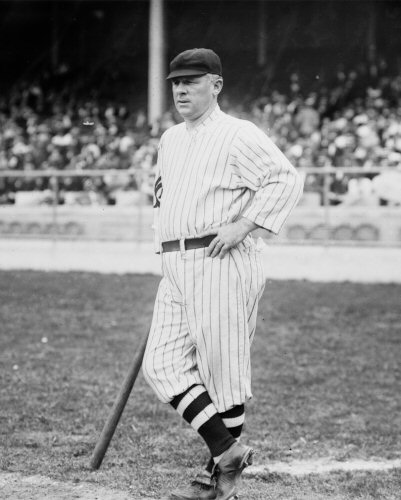

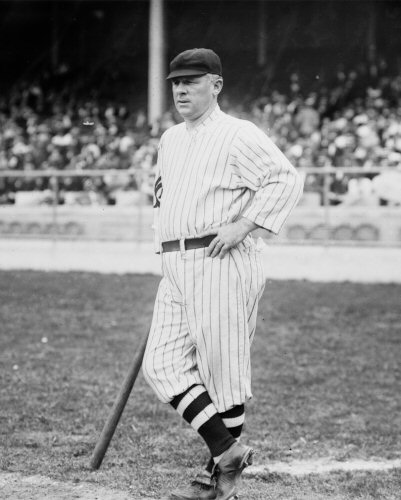

3. Everyone knows Ted Williams was the last man to hit .400 in the American League, some 75 years ago. The last NL player was Bill Terry, who banged out 254 hits (still the NL record) while hitting .401 in 1930. Terry was a bit of a late bloomer. He'd begun his pro career as a pitcher, and was already 24 years old when he was shifted to first base. The Giants purchased his contract the next year, but he spent his first few seasons stuck behind George Kelly. He was already 28 years old before he finally became an everyday player. He only had nine seasons as a regular, but he still managed almost 2200 career hits, and a .341 lifetime average. In the midst of it, he was the man who replaced the legendary McGraw as the Giants' manager, and led them to a World Series title in his first full year at the helm. As a player, he's been overshadowed by the great first basemen active in other league at the same time - Gehrig, Foxx, Greenberg. Terry was a different kind of player, but a deserving Hall of Famer nonetheless.

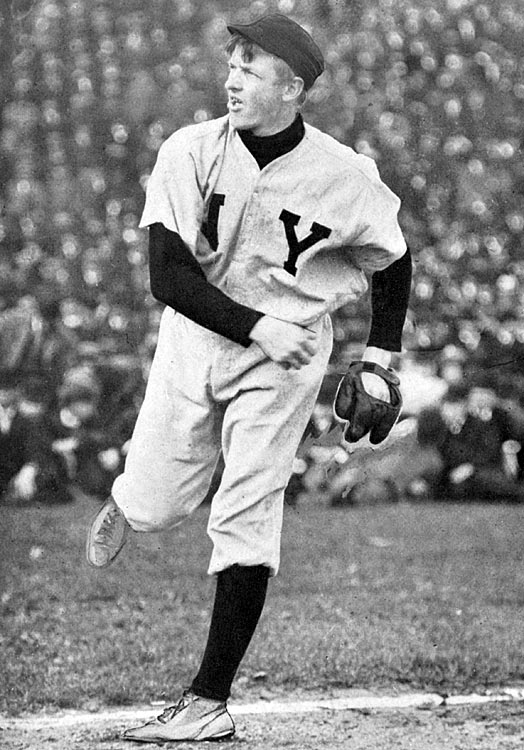

4. In September 1925, a 16 year old from Louisiana showed up in New York to try out for John McGraw, having been sent there by the owner of his local semi-pro team. McGraw was so impressed that he signed the youngster to a contract. Then, rather than trust his development to some minor league manager, McGraw had young Mel Ott spend the next two years sitting on the Giants' bench, where he could learn the game directly from McGraw and his players. It's amazing to me that this actually worked - there were only sixteen major league teams and the competition for jobs was not pretty. Most veterans did not normally lend a helping hand to some youngster. But Ott really was one the game's famous nice guys, as Durocher would observe, and apparently the older players all took a liking to him. Ott moved into the lineup in 1928, still just 19 years old, and promptly led the Giants with 18 HRs. He spent eighteen seasons in the Giants lineup, and he led his team in home runs each and every year, a feat unique in the annals of the game. He was the first National Leaguer to clear 500 home runs, an accomplishment that is generally discounted to some degree because he hit 323 of his 511 at the Polo Grounds. But while the foul lines were famously short, the Polo Grounds wasn't a great hitter's park. (Ott hit .311/.408/.510 in his road games.) The power alleys were very deep, and the wall in dead centre field was well-nigh unreachable, unless you could hit a baseball 450 feet. Ott was especially famous in his day for his unusual swing - while lots of players in today's game lift their front leg as a timing mechanism, no one else did it back then. He was indeed too nice a guy to be a good manager, but he was establishing himself as a broadcaster when he and his wife were critically injured in a head-on collision when another car lost track of the road on a foggy night. Ott died a week later, just 49 years old.

5. For some reason, the National League was overrun with LH hitting catchers in the 1960s. There was Ed Bailey, John Roseboro, Smokey Burgess, Tim McCarver, Clay Dalrymple all playing regularly, along with guys like Jesse Gonder and Vic Roznovsky getting a chance. Burgess and Bailey were the best hitters, and Roseboro and Edwards were the best defensive players but McCarver and Tom Haller of the Giants were the most complete players. Haller, tall and lanky, was built more like a first baseman than a catcher. He was named to three NL All-Star teams and later served as the Giants' GM in the early 1980s.

6. He doesn't belong in the Hall of Fame, but Travis Jackson was a fine player all the same. He was a teenager when he came up to stay in 1923; he took over the full time shortstop job in 1924 and played very well for the next eight seasons. Unfortunately, he was subject to random illnesses - an appendectomy, mumps, and influenza all took chunks out of his best seasons. And then his knees went bad on him before he turned 30. The knee problems, and the attendant surgeries, caused him to miss most of two seasons, and soon forced his move from shortstop to third base. The number was also worn by Robbie Thompson, another fine middle infielder whose career was shortened by injury, and J.T. Snow, defensive whiz and protector of small children hanging out near home plate.

7. A boy emerges from the mean streets of the San Diego ghetto to achieve major league stardom, becomes a World Series champion, wins an MVP award... yeah, probably too good to be true. Kevin Mitchell never quite left the hood. The friends he made there remained his friends, the ways he learned there remained his ways. Which is why someone who was as great a natural hitter as you will ever see ended up having such a strange, peripatetic career. Everyone wanted to get that bat in the lineup. But upon closer examination, no one wanted to keep the guy who swung that bat around, and got rid of him as quickly as possible. Mitchell was the NL MVP in his second full season with the Giants. This was his fourth season in the majors, already playing for his third team. That's what probably encouraged the Giants to keep him around for another two years (much longer than anyone else ever put up with him.) Eventually even the Giants said "Enough, already." There are all kinds of wild stories about Mitchell, and some of them may even be true. We do know he couldn't be bothered to stay in shape, or work very hard at his game. We do know he ran with some pretty shady characters. We know he was - and apparently still is - prone to settling things with his fists. We know that he was absolute poison in the clubhouse. But man, could he hit.

8. The Giants team that Bill Terry inherited from McGraw went on to finish sixth in 1932, and Terry's priority for the upcoming season was to improve their run prevention, second worst in the NL. To that end, he made two trades: he brought in light hitting defensive whiz Blondy Ryan to play shortstop in place of the gimpy Travis Jackson, and he obtained Gus Mancuso to replace Shanty Hogan behind the plate. It's always nice when things work exactly as planned. The Giants allowed the fewest runs in the league in 1933, and won the pennant and the World Series in Terry's first year as a manager. Hal Schumacher and Freddie Fitzsimmons both shaved almost 1.5 runs from their ERAs. Even the great Carl Hubbell was helped; he went from 181-11, 2.50 to 23-12, 1.66 with Mancuso receiving much of the credit.

9. The Giants selected Matt Williams out of UNLV with the third pick of the 1986 draft. The following April, having never played a game above A ball, he was their Opening day shortstop. He wasn't ready, and he wouldn't be ready for a couple more years. He made it to stay in the second half of 1989; taking over at third base after his July recall, he batted just .218 but he bashed 16 HRs in just 63 games and added another in the World Series. Over the next five years, Williams was essentially Mike Schmidt-lite: a great glove at third, with lots of HRs and lots of of strikeouts, lacking only Schmidt's tremendous plate discipline. Still a helluva player. In his first full season, he slugged 33 HRs and drove in 122; the year after that he won the first of his six Gold Gloves. In 1994, he was threatening to take a run at the single season HR record (he'd hit 43 in 114 games) when the strike ended the season. After a couple of injury-troubled seasons, the Giants traded him to Cleveland in the Jeff Kent deal. Williams homered in the 1997 World Series for the Indians, who then traded him to Arizona, where he finished his career. He had a couple more big seasons with the D'Backs, and homered in another World Series, this time for a winner. I believe that makes Williams the only man to hit a World Series home run for three different teams.

10. The first man of note to wear this number was Harry Gumbert, a middle of the rotation guy for New York in the late 1930s; since then it's mostly been the property of light-hitting shortstops like Buddy Kerr, Johnnie LeMaster and Royce Clayton. So let's salute a pioneer. In 1964, the Nankai Hawks of the Japanese Pacific League sent a very young LH reliever named Masanori Murakami to San Francisco's A ball affiliate, as a kind of exchange program. They then neglected to call him home in June as originally planned. This suited the Giants just fine - Murakami was far too good for the California League, where he'd posted a 1.78 ERA while striking out 159 batters in 106 innings. So the Giants brought him to the majors when the rosters expanded and on September 1, 1964 he became the first Japanese born player to appear in a major league game. Even if it was against the Mets. Murakami pitched very well that month, well enough to set off an international dispute. The Giants wanted to keep him, the Hawks wanted him back. It was eventually agreed that he'd spend one more year in North America, and then return home. He gave the Giants one more season (having switched his number to 37), and went home to pitch for another 17 years in the JPPL.

11. In 1926, the Detroit Tigers purchased the contract of a lanky left-hander named Carl Hubbell. But once the Tigers had Hubbell in their system, they decided they didn't like him all that much. In particular they didn't like his reliance on the screwball. Ty Cobb believed it damaged pitchers arms and Hubbell was ordered not to throw it. Hubbell did not fare particularly well without his best pitch, and was ready to give up baseball unless he could get free of the Detroit organization. Happily, he did. Detroit sold Hubbell's contract to Beaumont in the Texas League, which is where he was seen, using his screwball again, by a Giants scout named Dick Kinsella. He liked what he saw and told John McGraw about him. McGraw wasn't worried about the screwball; McGraw had watched Christy Mathewson dominate the National League for almost fifteen years with the same pitch. In July, the Giants purchased Hubbell's contract, put him in their starting rotation, which is where he stayed for the next sixteen years. He had a dazzling five year peak from 1933 through 1937, winning at least 21 games each season and walking off with two NL MVP awards. Even so, he's probably best remembered for his performance in an exhibition game. In the 1934 All-Star game, played before Hubbell's hometown fans at the Polo Grounds, Hubbell struck out Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmie Foxx to end the first inning, and opened the second by fanning Al Simmons and Joe Cronin. By the time he retired, he had won more games than any left-hander in NL history.

12. A "tweener" is a basketball concept - a player who's not quick enough to play small forward, not big enough to match up with power forwards. The baseball equivalent is an infielder whose glove isn't quite good enough to play second base, but doesn't have as much bat as you want from your third baseman. That's what Jim Davenport was, although his glove at third was good enough that the Giants generally decided they could live with his bat. He spent his entire playing career with the Giants, and worked for the organization in all kinds of capacities for more than 30 years after he was done playing - major league coach, minor league manager, scout, instructor. They gave him a shot at managing the big league team in 1985. It did not go well - the team was 56-88 when he replaced by Roger Craig, and that 1985 team is the only Giants team to lose 100 games. The only one!

13. Most notable here are a couple of infielders on the downside of their careers, Edgardo Alfonzo and Omar Vizquel, who actually won two Gold Gloves during his tenure with the Giants. The idea that Vizquel, at age 39, was a better player at shortstop than Adam Everett or Rafael Furcal is utter lunacy, of course.

14. When Jesus Alou, younger brother of Felipe and Matty, joined the Giants in September 1963, broadcasters around America didn't know what to do. They simply couldn't call him by his name. They didn't know to pronounce it, and they wouldn't say "Jesus" because that would have been blasphemy or something. Seriously. So they called him "Jay Alou." If the Alous were the DiMaggios at a much lower level, Jesus was Vince. Unlike the DiMaggios, they all came up with the same organization. They never did start together in the outfield (the Giants already had a pretty good centre fielder) and Felipe was traded to the Braves after the 1963 season, Matty to the Pirates after the 1965 season. But the Giants' game on September 15 1963 concluded with Jesus in LF, Felipe in CF, and Matty in RF. Pretty cool.

15. The Big Cat, Johnny Mize, gave the Giants a couple of sensational seasons - in 1947 he became the only man in history to hit more then 50 home runs while striking out less than 50 times - but Johnny Mize was a Cardinal. And he didn't get along with Leo Durocher, so the Giants essentially donated him to the Yankees midway through the 1949 season. As if the Yankees needed the help. So let's acknowledge a future Hall of Famer walking the diamonds of America right now. Every manager with three World Series titles is in the Hall of Fame - that's the magic number. Bruce Bochy now stands 16th on the list of games won by a manager, and he'll go by Jim Leyland this year. He's been at it for 22 years, but at age 61 he could easily carry on for another five years or so. In which case he should easily clear 2000 wins (only 10 managers have as many, and they're all in the Hall.)

16. A difficult choice here between two players whose life away from the ballpark took a wrong turn. Jim Hart moved Jim Davenport off third base in 1964. Hart didn't like playing third base, with good reason - he was terrible at it, error prone with limited range. But he could really hit. As a 22 year old rookie, in the heart of the second dead-ball era, Hart hit .286/.342/.498 with 31 HRs and proceeded to duplicate that production over the next four years. In 1969, his age 27 season, the strike zone was returned to normal and expansion added twenty minor league pitchers to the NL. Did Hart's production explode? It did not. He just stopped. He couldn't stay on the field, for one thing. Over the next four years, his age 27-30 seasons, Hart played 95, 76, 31, and 24 games. He couldn't stay healthy, and he also couldn't stay sober. He was out of baseball by the time he was 32. He ended up living on the streets picking up loose change to buy liquor. Happily, he did turn his life around. But I want to remember Hank Thompson, whose story follows a similar arc. Thompson was the third African-American to play in the majors after the blacklist was broken in 1947. He'd started out with the Kansas City Monarchs at age 17, but was drafted into the US Army (he served at the Battle of the Bulge) before returning to the Monarchs. In July 1947, still just 21 years old, he joined the St.Louis Browns. Two days after signing Thompson the Browns also signed Willard Brown, the great Negro League slugger. This did not work out, mainly because the Browns, front office and players, didn't really want it to work out, and they would get rid of both players within six weeks. Willard Brown never played in the majors again. He hit one homer as a Brown and one of his own teammates deliberately smashed his bat afterwards. Thompson, eleven years younger, would get another chance. He and Monte Irvin joined the Giants together in July 1949. Thompson settled in right away at second base, switched to third base in 1950 and had a very nice season - .289/.391/.463 with 24 HR and 91 RBI. He struggled at the plate the following year, and in late July Durocher sent Thompson to the bench, switched outfielder Bobby Thomson to third base, and installed Don Mueller in right field. That worked out rather well, actually. Thompson bounced back in 1952 and gave the Giants four good years in a row, playing mostly third base but also filling in at second base and the outfield as needed. He had an off-year in 1956, and the Giants sent him to the minors in 1957. Thompson played one year in AA, and decided he was through with baseball. He drove a cab, he drifted to Texas, he was arrested for armed robbery and sent to prison. Upon being paroled after three years, he started working with underprivileged children for the city of Fresno. Unhappily, this turnaround story came to a sudden and unhappy ending when he died suddenly of a seizure at age 43.

17. Some of us remember Randy Moffit wearing this very number as he emerged out as a crowd at the relief ace by default of the 1983 squad, Toronto's first good team. Bobby Cox was one of the greatest managers the game has ever seen, and one of the best ever at the care and maintenance of starting pitchers. But Cox was not particularly good at running a bullpen, or identifying useful relief pitchers. Moffit picked up three wins for the Jays in April, and didn't allow a run until the middle of May, by which time he was the closer, more or less. It was all downhill from there. His arm basically fell off in the second half of the season (7.06 ERA), and he never pitched in the majors again. Well - he'd left his arm in San Francisco, high on a hill...

18. I would assume you're all familiar with Matt Cain, a very fine pitcher through 2012. He's been battling all kinds of physical problems since, but he's still in the rotation.

19. To me, Lake Charles Louisiana will always be where I'll find that little Bessie girl that I once knew. That's where Alvin Dark grew up. Dark was a tremendous athlete, who turned down a basketball scholarship from Texas A&M to play football at LSU, where he was the star tailback, while also playing baseball and basketball. But there was a war, and he enlisted in the Marines in 1943. When the war was over, he was drafted by the NFL's Philadelphia Eagles. But by then Dark had decided that he preferred baseball and signed with the Boston Braves in late 1946. He took over as the Braves' shortstop in 1948, and was the Rookie of the Year Award, hitting .322. The Giants traded four players, three of them everyday regulars, to obtain Dark and veteran second baseman Eddie Stanky. Dark held the New York shortstop job for the next seven years, the heart of his career (which didn't get started until he was 26 years old - as noted, the man went first to university and then to war.) It was Dark who led off that fateful ninth inning against Newcombe in September 1951, Dark who fouled off several two-strike pitches before striking a single that just tipped off Gil Hodges' glove. A rally begins...

20. The Giants didn't get around to retiring this number in honour of Monte Irvin until a few years ago. I'm not sure what they were waiting for. They were unlikely to find anyone better to give it to. They'd been trying for 50 years. Irvin was already 30 years old before he got a chance to play in the majors, but he did his best to make up for the lost time. He gave the Giants some tremendous seasons in the early 1950s (.314/.403/.511 from 1950-53) - but by the time they made their championship run in 1954, he was 35 years old and the decline was setting in. He was a line drive hitter, with medium power and very good plate discipline.

21. San Francisco was the fourth stop for Jeff Kent, and it's where he broke through to become an All-Star and win an MVP. He made the Blue Jays out of spring training in 1992, having skipped AAA completely. The problem for Kent was that he was a second baseman on the team that employed Roberto Alomar. He went to the Mets in the David Cone deal, stayed there for four years before being dealt to Cleveland for Carlos Baerga - the Indians then flipped him to the Giants a few months later for Matt Williams. Kent was always a fine hitter, but he was considerably more productive in San Francisco, forming a formidable L-R combination in the heart of the lineup with Barry Bonds. Batting behind Bonds meant Kent was getting an ungodly number of at bats with someone on base. He'd never driven in more than 80 runs in his career - in his six years by the Bay, he never drove in fewer than 101. Things eventually went a little sour - he clashed with Bonds, he got into a dispute with his own team when it turned out he'd lied about how he had incurred a pre-season wrist injury. He's a somewhat complicated Hall of Fame case - obviously, he's been a much better hitter than most second baseman in the Hall. The argument is about whether he was a bad defensive player, a competent one, or an underrated one.

22. Rafael Palmeiro and Will Clark played together at MIssissipi State (Palmeiro played outfield), and they were both first round picks in the 1986 draft. When Palmeiro left Texas after the 1993 season, they signed Clark to replace him; when Palmeiro left the Orioles after 1998, they signed Clark to replace him. Clark was clearly the better of the two players, of course. His Hall of Fame case has two problems: he's got the Fred McGriff issue, in that his great early seasons took place in a low-run environment, so his raw counting numbers don't look as impressive as what everyone and his cousin was doing in the late 1990s. And he retired young, at age 36, having just hit .319/.418/.546 for Baltimore and St.Louis.

22. Rafael Palmeiro and Will Clark played together at MIssissipi State (Palmeiro played outfield), and they were both first round picks in the 1986 draft. When Palmeiro left Texas after the 1993 season, they signed Clark to replace him; when Palmeiro left the Orioles after 1998, they signed Clark to replace him. Clark was clearly the better of the two players, of course. His Hall of Fame case has two problems: he's got the Fred McGriff issue, in that his great early seasons took place in a low-run environment, so his raw counting numbers don't look as impressive as what everyone and his cousin was doing in the late 1990s. And he retired young, at age 36, having just hit .319/.418/.546 for Baltimore and St.Louis.

23. Clint Hartung was one of the most heralded prospects of all time, spoken of as a future Hall of Famer before he had even played a major league game. Really. All the Giants had to do was figure out whether to wanted him to hit or pitch. It's hard, at this remove, to understand what everyone saw in him. Hartung showed promise as a 19 year old minor leaguer, but he went off to war, and didn't start playing baseball again until 1947. He started out in the majors as a pitcher, and after a few years of uninspiring performance, was switched to the outfield. He wasn't good enough to crack the starting lineup, and Leo Durocher simply did not let the guys in his bench play in any games. So Hartung sat on Durocher's bench and waited for someone to break a leg. And in 1951, someone broke a leg. In the ninth inning of the playoff against the Dodgers, after Dark's leadoff single Don Mueller hit a single to RF. Newcombe retired Monte Irvin, but Whitey Lockman lined a double to left-centre. Dark scored, Mueller slid into third... and broke his ankle. Hartung (by now wearing #26) came off the bench to run for Mueller. Dodgers manager Charley Dressen summoned Ralph Branca to relieve Newcombe as Bobby Thomson came up to bat. Thomson, born in Glasgow, was in his fifth full season with the Giants. He'd been their centre fielder until Willie Mays moved him to LF - he'd spent the last two months of 1951 as the Giants' third baseman, after Durocher had banished Hank Thompson to the bench. He'd have his last good season with the Giants in 1953, but he hung around with various teams right up to 1960. He was a good player. But, of course, all anyone will ever, ever remember is what he did with the second pitch Branca threw to him. "The Giants win the pennant!"

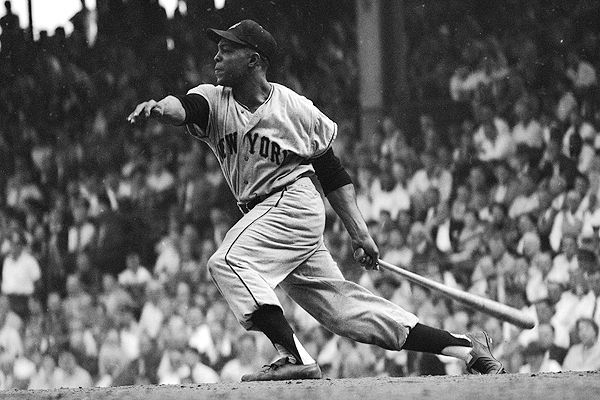

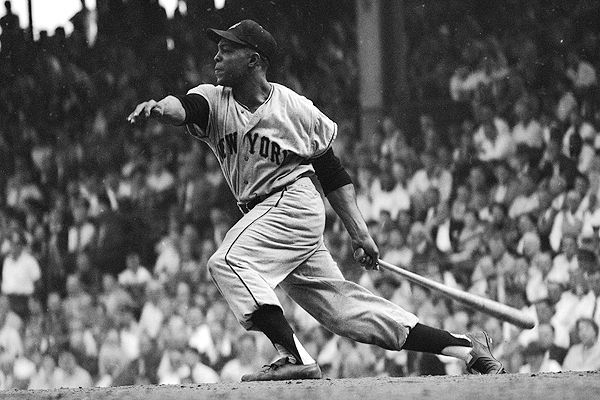

24. When Thomson went up to the plate against Branca, the next hitter waited in the on-deck circle, hoping desperately that whatever happened, it would end the game. He may have been the National League Rookie of the Year, but he was still just a 20 year old kid from the outskirts of Birmingham. He was was afraid of the moment, afraid it would all come down to him, and it bothered him that he was afraid. He promised himself he would never be afraid on a baseball diamond again. Was Willie Mays the greatest baseball player who ever lived? I'm certain that at his peak in the mid 1950s Mickey Mantle, born the same year as Mays, playing the same position in the same city, was the greater player of the two at the time. We're all certain that Ruth and Williams were greater hitters. Fine. Willie Mays was as close to perfection as a baseball player could possibly be. No one's game has ever been more complete. There was nothing he couldn't do. His peak, great as it was - and that was very great indeed - may not have reached quite as high as Mantle's - but Mays extended his greatness over a much longer period than Mantle was able to do. While Ruth and Williams were indeed more productive hitters than Mays, Willie Mays was a great hitter himself, and far superior to both in every other facet of the game. Mays was a much better teammate. He was much more durable. He was the smartest baseball player I've ever seen or ever heard about, the greatest baserunner, the greatest outfielder. Willie Mays, people. The greatest living baseball player. Now and forever.

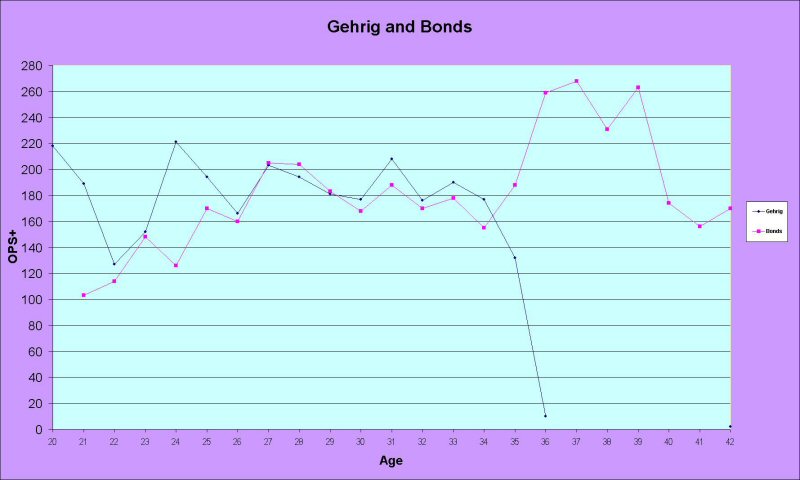

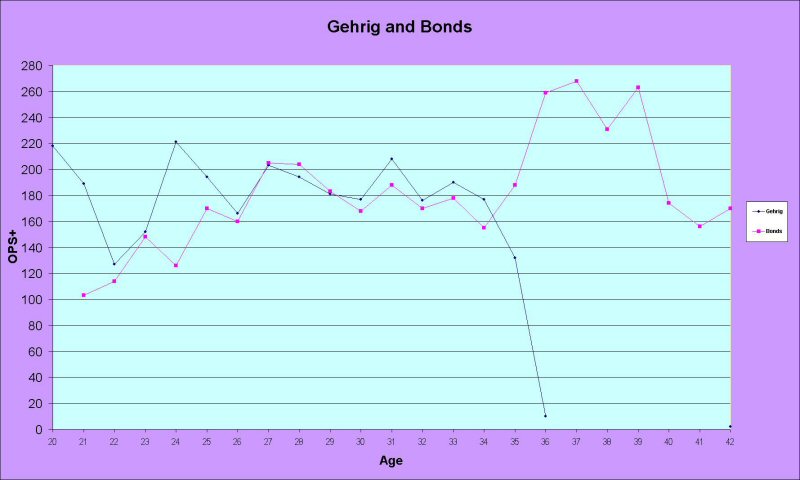

25. I imagine you're all pretty familiar with Barry Bonds, so I'd like to recycle a graphic I devised for this piece back in 2008. It simply tracks the OPS+ of Bonds and Lou Gehrig by age. It's astonishing how closely the two men track each other - Gehrig's usually just a little bit better, but if you're hanging with Lou Gehrig, you're awfully special yourself - until Gehrig suddenly gets sick and Bonds suddenly ascends to some higher plane of existence.

This was also the number worn by Bobby Bonds, father of Barry. Bobby was essentially a RH version of his son, just not quite as good. Unlike his offspring, Bobby's arm was good enough to play right field (Barry's wasn't good enough for centre.) Bobby came up midway through the 1968 season, played just great for the next seven years, and got nothing but grief for his troubles. There were two problems. No one, in the history of the game, had ever struck out as often. In his first full season, he established a new single season record by by whiffing 187 times; in his second season, he topped that with 189 Ks (a mark stood for more than 30 years until Adam Dunn came around). This bothered people. The second problem? Well, it turned out he wasn't Willie Mays. Which meant he was a disappointment. So they traded him to the Yankees for another outstanding player seen by his home crowd as something of a disappointment (Bobby Murcer, who was really good, but he wasn't Mickey Mantle. Or Joe DiMaggio.)

This was also the number worn by Bobby Bonds, father of Barry. Bobby was essentially a RH version of his son, just not quite as good. Unlike his offspring, Bobby's arm was good enough to play right field (Barry's wasn't good enough for centre.) Bobby came up midway through the 1968 season, played just great for the next seven years, and got nothing but grief for his troubles. There were two problems. No one, in the history of the game, had ever struck out as often. In his first full season, he established a new single season record by by whiffing 187 times; in his second season, he topped that with 189 Ks (a mark stood for more than 30 years until Adam Dunn came around). This bothered people. The second problem? Well, it turned out he wasn't Willie Mays. Which meant he was a disappointment. So they traded him to the Yankees for another outstanding player seen by his home crowd as something of a disappointment (Bobby Murcer, who was really good, but he wasn't Mickey Mantle. Or Joe DiMaggio.)

26. We're torn here between two players with excellent names, who had their moments of glory, even if they didn't last all that long. John (The Count of) Montefusco was the 1975 Rookie of the Year, (15-9, 2.88, 215 Ks) and pitched well for three seasons before gradually sliding into mediocrity. But Dusty Rhodes (born James Lamar Rhodes) is an even better nickname, even if it is kind of obvious. Rhodes played just 576 games in the majors and almost half of them (277) were as a pinch hitter. He is one of the very few men in baseball history to receive MVP votes for his work as a pinch-hitter. In 1954, he appeared in just 82 games (47 of them as a pinch hitter) - he hit .341/.410/.695 with 15 HRs and 50 RBI in just 164 ABs. In the first game of the World Series against the Indians (the one in which Mays made The Catch), Rhodes pinch hit for Monte Irvin in the 10th inning of a 2-2 tie and hit a three-run walkoff homer against Bob Lemon to win the first game. He pinch hit again for Irvin in the second game, with the Giants down by a run, and delivered an RBI single off Early Wynn to tie the game; he stayed in and added s solo homer to put the Giants up 3-1. He pinch hit for Irvin again in the third game, and delivered a two-run single to put the Giants ahead 3-1. There was no official World Series MVP in 1954, but if there had been, how could you not give it to the pinch-hitter?

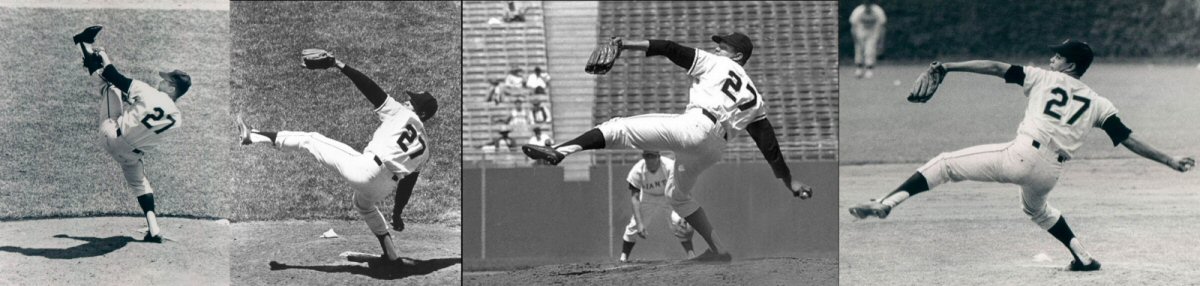

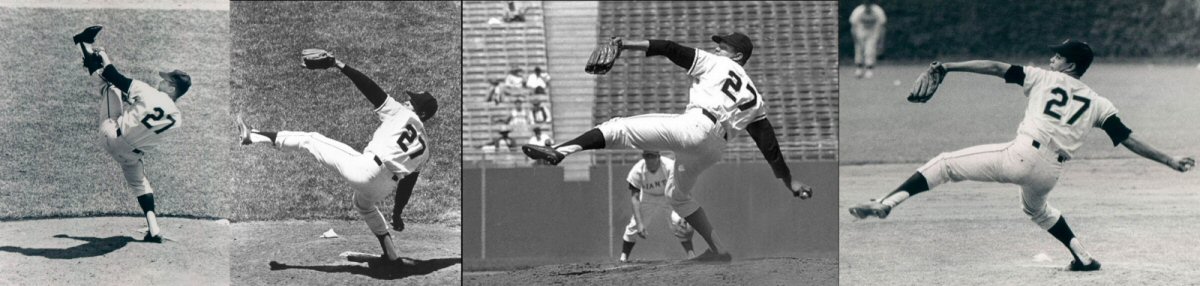

27. I think there's a pretty good argument to be made that the greatest pitcher of 1960s was not Sandy Koufax, not Bob Gibson, but rather Juan Marichal, the Dominican Dandy. He can't match Koufax's dazzling four year peak from 1963-66 - not too many could - but Marichal went 93-35, 2.31 himself over those four seasons, winning at least 21 games each year. And Marichal didn't have Dodger Stadium working on his behalf. Koufax, of course, walked away after 1966 while Marichal kept right on going, winning 26 games in 1968 and 21 in 1969. Marichal didn't get to start nine World Series games like Gibson, and showcase his greatness to the entire baseball world - in his only WS start, Marichal pitched four shutout innings but injured his hand bunting in the fifth inning and had to leave the game. But over the decade, Marichal went 191-88, 2.57, while Gibson was 164-105, 2.74 - and each season, more often than not - Marichal was generally just a little better than Gibson (with the obvious exception of 1968, although Marichal's 26-9 2.43 isn't too shabby.) Hey, let's make a Data Table:

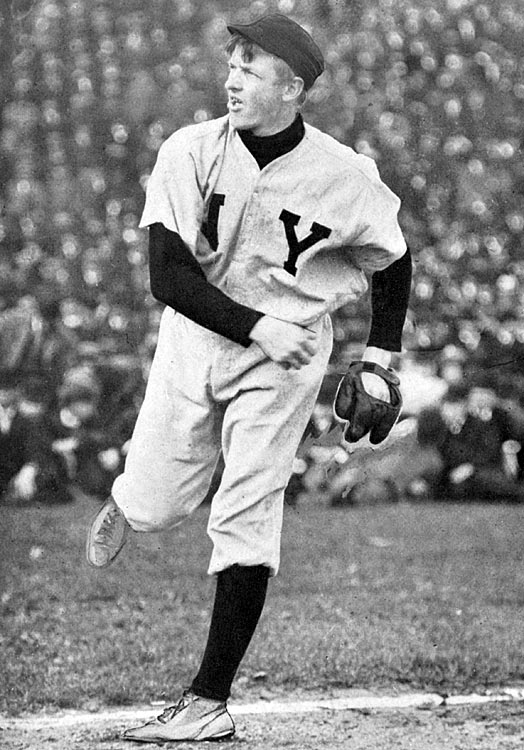

Both pitchers, of course, are still remembered for the way they delivered their pitches - Gibson with his double pump, then leaping off the mound at the hitter with bad intent, Marichal with.. well, take a look:

It's difficult to imagine, but somehow he made this look easy and graceful. He was one of the greatest control pitchers of the decade; he didn't strike out quite as many battters as Gibson (and no one struck out as many as Koufax) he didn't walk as many either. Anyway, his greatness is hardly in dispute. He won more games than any Dominican pitcher ever.

Year Marichal Gibson

1960 6- 2 2.66 3- 6 5.61

1961 13-10 3.89 13-12 3.24

1962 18-11 3.36 15-13 2.85

1963 25- 8 2.41 18- 9 3.39

1964 21- 8 2.48 19-12 3.01

1965 22-13 2.13 20-12 3.07

1966 25- 6 2.23 21-12 2.44

1967 14-10 2.76 13- 7 2.98

1968 26- 9 2.43 22- 9 1.12

1969 21-11 2.10 20-13 3.12

Both pitchers, of course, are still remembered for the way they delivered their pitches - Gibson with his double pump, then leaping off the mound at the hitter with bad intent, Marichal with.. well, take a look:

It's difficult to imagine, but somehow he made this look easy and graceful. He was one of the greatest control pitchers of the decade; he didn't strike out quite as many battters as Gibson (and no one struck out as many as Koufax) he didn't walk as many either. Anyway, his greatness is hardly in dispute. He won more games than any Dominican pitcher ever.

28. He's not even 30 years old yet, but Buster Posey is already the greatest catcher in the long, long history of this franchise. Working on a Hall of Fame resume as we speak.

29. The Braves drafted Jason Schmidt out of high school in the eighth round in 1991, but he had some trouble cracking that rotation. The Braves packaged him to Pittsburgh in the Denny Neagle trade. He was a solid starter for the Pirates over five seasons, and was traded to the Giants at the deadline in 2001. The Giants were contenders that year - they would win 90 games and just miss the post-season - and pitching for a good team seemed to bring out the best in Schmidt. He went 7-1 over the rest of 2001, 13-8 the following year - and in 2003, he probably deserved the NL Cy Young Award for going 17-5, 2.34. Schmidt gave the Giants three more strong seasons before signing with the Dodgers as a free agent. And presto - his arm fell off as soon as he arrived in LA. The Dodgers paid $45 million over three years for just 10 starts (3-6, 6.02)

30. San Francisco's first home-grown hero was the Baby Bull, Orlando Cepeda, a cheerful Puerto Rican who homered in his ML debut - the first game the Giants played in San Francisco - and went on to win the NL Rookie of the Year Award, hitting .312 with 25 HRs at age 20. He was doing even better in his second season. But the Giants had come up with another young first baseman, Willie McCovey, who was simply destroying AAA (.372 with 29 HR and 95 RBI in 92 games) and at the end of July, they brought McCovey to the majors. McCovey hit .354 with 13 HRs in just 52 games, became the second Giant

first baseman in as many years to be the NL Rookie of the Year, and set up an extremely awkward job share that it took the Giants years to resolve. First they tried Cepeda at third base - he had played there in the minors - but he made three errors in four games, hated every second and said so. Loudly and often So the Giants moved Cepeda to left field - he didn't like that either, but he couldn't do as much damage playing there. For three years, the two split time at first base, with Cepeda getting full time ABs by playing OF when McCovey was in the lineup. Cepeda kept hitting all the while - through age 25, he's basically matching Henry Aaron - didn't like this arrangement either and Cepeda was never one to keep his thoughts to himself. He was a boisterous, excitable guy, with a big personality - one suspects he liked playing 1B because he liked the action. Cepeda looks back on this now with regret. He says he knows he could have made

himself into a competent left fielder if he'd tried - it was all pride

and ignorance, he says - but in fairness, he was just 21 years old, and he was the local hero. In 1963, Al Dark tried a new approach, moving McCovey to the outfield. This was hilarious. In the outfield, McCovey, 6-4 with long arms, and huge narrow feet, resembled a large exotic bird with a glove, a heron perhaps. Maybe a flamingo. But Cepeda had accumulated some serious knee injuries along the way (playing the outfield - maybe he had a point) and the Giants finally resolved the situation by trading him, when his value was at it its lowest, to St.Louis. Where he stayed healthy and productive long enough to win an MVP and lead the Cardinals to a World Series title.

31. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Giants were producing outfielders the way Detroit used to produce cars - one after another. Their system produced Bobby Bonds, George Foster, Gary Mathews, Dave Kingman - All-Stars at the very least, every one of them - as well as guys like Ken Henderson, Gary Thomasson, and Larry Herndon who were all good enough to play regularly. Obviously, they couldn't keep everyone. They brought Garry Maddox to the majors in 1972, when he was 22 years old , and he gave him three good seasons before the Giants sent him to the Phillies for Willie (the Wandering First Baseman) Montanez. Maddox didn't walk very much and he didn't hit many home runs. He hit for a good average, slashed lots of doubles and triples, and earned his keep with his defense. He was a wonderful centre fielder, as the nine Gold Gloves do sort of suggest. They used to say that two-thirds of the earth is covered by water, the rest by Garry Maddox.

32. LaTroy Hawkins played everywhere, always wearing this number if he could, but he only spent half a season with the Giants. Ron Bryant was just 21 years old when he made the Giants to stay as a LH swing man. He was a LH finesse pitcher who walked a few more batters than you'd like to see. He gradually moved closer and closer to becoming a full-time starter. In 1972, he went 14-7 2.90, which did the trick. He was in the rotation the next year, and darned if he didn't win 24 games, the only NL pitcher to win 20 games in 1973. The following March, he hurt himself in a swimming pool accident. He fell off a slide, and cut his right side badly (25 stitches required to close the wound.) So much for spring training. Did the Giants send him on a rehab assignment once the injury had healed, let him get stretched out and ready to start major league games? They did not. They stuck him right back into the rotation in late April, and NL hitters let the good times roll. Bryant went 3-15, 5.61 and never won another major league game afterwards.

33. It's a tough call here between three RH starters, each of whom spent about five years as a number 2-3 starter in the Giants' rotation. John Burkett was the most recent - he had the year of his career in San Francisco, going 22-7 for the 1993 Giants. Jack Sanford was the guy behind Juan Marichal for the early 1960s teams, and in the midst of his time in San Francisco he came up with a 24-7 season for the 1962 pennant winners. Jim Barr never had a season quite like that - he never won more than 15 - but he was probably a slightly better pitcher than either Sanford or Burkett, he stayed with the Giants longer, and of course over two starts in August 1972, he retired 41 consecutive batters (the last 20 batters in a two-hit shutout against the Pirates, and then the first 21 in a three-hit shutout of the Reds.) The record was tied by Bobby Jenks in 2007, broken by first Mark Buehrle in 2009 and Yusmeiro Petit in 2012,.

34. What, you don't remember Ron Herbel? Neither do I, really. He was a RH swing man with the Giants in the mid 1960s. Hey, it's him or Dave Burba.

35. They didn't call Sal Maglie "The Barber" because he generally looked as if he needed a shave. He was the Barber because was the one providing the close shaves. Don Drysdale, who encountered an aging Maglie in Brooklyn when he was starting out, always gave Maglie lots of credit for his own success - "he taught me how to pitch inside." Sal Maglie had one of the strangest careers imaginable. He was born in Niagara Falls, the son of Italian immigrants. He was a good enough high school basketball player to get a university scholarship, but he much preferred baseball. He wasn't actually very good at baseball at this stage, but he persevered. He was playing semi-pro in Niagara Falls when former major league catcher Steve O'Neill saw something he liked and signed Maglie to his AA ball team in Buffalo. Where he pitched, badly, for three seasons. Dropping down a level to A ball in 1941, he figured something out, and pitched well for Jersey City in AA the next year. And then he quit. The war was on. Maglie had failed his pre-induction physical, but he went to work in a defense plant for the next two years. He returned to baseball in 1945, pitching for Jersey City, and not particularly well. Even so, in mid-season he suddenly found himself in the big leagues. There was a war on, and a serious shortage of ballplayers. One armed men were playing in the majors. Why not a 28 year old pitcher with a career 38-47 record in the minors. But Maglie did quite well (5-4, 2.35), and the Giants assumed he'd be part of their rotation in 1946. Instead, he jumped to the Mexican League, which was offering him more money than the Giants. Maglie, and the other "jumpers" were banned from the major leagues for five years. Maglie's Mexican adventure lasted just two seasons. Still barred from the majors, he barnstormed a bit, played in Quebec for a while, and started a business with the money he'd earned in Mexico. The ban was lifted a year early, and Maglie returned to the Giants in 1950. He was 33 years old, and he'd started just 10 games in the major leagues, and that had been five years earlier. It didn't matter. He'd learned a few things along the way, most of them involving the art of intimidating hitters. He went 18-4 and led the league with a 2.71 ERA in his first full season. He followed that with a 23-6 mark in the Giants miracle year of 1951. The Giants came from 13 games back in mid-August to tie the Dodgers and force a three game playoff. In the winner-take-all final game, Maglie hooked up with Don Newcombe in a tight pitcher's duel. The Dodgers broke through for three runs in the eighth to take a 4-1 lead. The Giants rallied in the ninth inning... well, you've probably heard about it. Maglie won another 18 games in 1952. By now he was 36 years old, and back troubles hampered him in 1953. But he bounced back to go 14-6 in 1954, and started the first game of the World Series against Cleveland. In the eighth inning, with the score tied 2-2, Maglie walked Doby and allowed a single to Rosen. At this point, Durocher brought in a southpaw reliever to face Cleveland's Vic Wertz, who retired him on a deep fly to centre field... you've probably seen the replay. The next season, Maglie was 9-5 for in mid-season when Cleveland obtained him on a waiver claim. No one knows why the Giants let him go, or why the Indians wanted him. He was in Cleveland for almost a year, and started just twice. He was ready to retire, when the Dodgers obtained him in a straight cash purchase and put him in the rotation. Where he went 13-5, 2.87, forming a formidable 1-2 punch with Newcombe, and found himself back in the World Series. Maglie beat Whitey Ford in the Series Opener. The Dodgers won game two as well, but the Yankees evened the Series with a pair of wins at the Stadium. Maglie got the call for Game 5 and was outstanding, allowing just five hits and two runs. But the other guy was a little better that day, a fellow named Don Larsen. After all these adventures, Maglie was 39 years old and just about done. He had one more good year as a part-time starter for Dodgers, and pitched briefly for the Yankees and the Cardinals before hanging 'em up. He spent most of the 1960s as a pitching coach - Jim Lonborg gave Maglie much of the credit for his breakout year in 1967 ("he taught me how to pitch inside") but Maglie and Dick Williams could not get along (Grouch, meet Grouch) and he was fired as soon as the 1967 season ended. Maglie was the pitching coach during the one and only season of the Seattle Pilots, where he didn't get along very well with Jim Bouton. Who wrote a whole book about that very season, as you may know. Finally, he left the game for good, retiring to Niagara Falls. Quite the ride.

36. When people think of Gaylord Perry, they don't think of the 300 wins or the two Cy Young Awards, or his mind-boggling durability and consistency. They think of the spitball. Which is exactly what Gaylord Perry wanted people to think. Especially hitters. He wanted the idea in the batter's heads. The Perry brothers came out of North Carolina. Jim made the majors first, in 1959, and won 18 games in his second season; Gaylord, three years younger, came up in 1962 and spent two years scuffling, just trying to make the team. He then spent two more years working as a swingman himself. He was 27 years old before he finally went into the rotation full-time. In his first season as a starter he won 21 games and made the All-Star team. He was just getting started. Over a 15 season span, Perry averaged 18 wins and 285 IP, picking up two Cy Youngs awards along the way; never pitching less than 200 IP, and six times more than 300. Unfortunately, in a historically bad trade, the Giants had traded him for the Ghost of Sam McDowell fairly early in this run - he did win 20 games twice for the Giants, but he won his Cy Youngs for Cleveland and San Diego.

37. Candelstick Point may not have been the best place in the world to build a baseball stadium. It was pleasant enough during the day, but in the evenings, fog and damp rolled in from the San Francisco Bay. Along with gusts of wind. Big, powerful gusts of wind. Strong enough to lift the huge cage teams use for batting practice into the air and set it down around second base. Such gusts would surely be strong enough to make a grown man lose his balance, especially if he happened to be standing on one leg at the time. That's what happened to Stu Miller in the first of 1961's two All-Star Games. As there were a couple of men on base, he was called for a balk, of course. If that's Miller is best remembered for it's a shame. Miller was basically the Keith Foulke of the 1960s. His fastball was in the low-to-mid 80s, and he didn't really have a breaking ball. Nevertheless, he pitched for 16 years in the majors, led both leagues in saves (with the Giants in 1961, with the Orioles in 1963). He did it all with that pedestrian fastball and a killer changeup, proving once more the eternal wisdom of Warren Spahn that: "Hitting is timing. Pitching is upsetting timing." The man who had the number before Miller was a LH reliever named Don Liddle, who gave the Giants three pretty good years out of the bullpen. Leo Durocher was probably the first manager who made a point of keeping a dependable southpaw available in his bullpen, and it was Liddle whom Leo called on to face Vic Wertz in the 1954 Series, the score tied and two men on base. Wertz, of course, smashed the ball about 440 feet to dead centre, but it was the Polo Grounds and Willie Mays was there. Durocher came right out to summon a new pitcher. Liddle gave him the ball and said "Well, I got my man."

38. I don't care how well some guy named Brian Wilson pitched for the Giants; the real Brian Wilson is a twisted genius, a man much too fragile for this rough world, but still America's greatest master of melody since Gershwin. So this spot goes to Greg Minton, who teamed up with Gary Lavelle to give the Giants an excellent L-R combo out of the bullpen. Bonus points for one the game's all-time great pickoff moves.

39. Bob Knepper had his best years with the Astros, so let's go with Mike Krukow, a tall RH who had a long career as a mid-rotation starter, never winning more than 13 games until at age 34 he unexpectedly pulled off a 20-9 mark for the 1986 Giants.

40. You all know about Madison Bumgarner. I just think it's wonderful that there exist a player known informally as "Mad Bum." That has to be, like, the Greatest Name Ever.

41. A year after trading Garry Maddox for Willie Montanez, the Giants shipped Montanez to Atlanta to obtain third baseman Darrell Evans. Evans had been drafted by Kansas City, but they'd let him escape to Atlanta in the Rule 5 Draft. Evans was a pretty crude third baseman but luckily for him, one of the greatest third baseman of all time (Ed Mathews) was working for the Braves, and helped Evans develop his skills. Evans had a big year in 1973, hitting 41 HRs - but his overall skills weren't the kind that were obvious to the baseball world at the time. He had power, but outside his one big season, he generally hit about 20-25 HRs; he did not hit for average, generally in the .240-.250 area. He was a very good third baseman, but he didn't dazzle you with his glove. He regularly drew 90+ walks a year, but it was the 1970s and most people just didn't notice. Evans was happy to return to California (he''s from Pasadena) but seeing as how the Giants already had the immortal Ken Reitz at third, he played first base when he arrived. That winter, they traded for Bill Madlock, and Evans moved to the outfield. But late in 1977, the Giants moved Madlock to second base and installed Evans at third, where he stamped out interchangeable seasons through 1982 while providing fine defense at third. He was moved to first base in 1983, and slugged 30 HRs in his final season as a Giant - he then joined the Tigers as a free agent, where he finally got to play in a World Series.

42. Michael Jackson pitched in more than 1000 major league games for eight different teams. He stopped in San Francisco along the way, naturally. But as we all know, the real Michael Jackson was a dancer. Marv Grissom pitched very well out of Leo Durocher's bullpen in the 1950s. But I like another swing man from the 1960s. Bobby Bolin, a tall, skinny RH was actually pretty good - or at least he was during the days of the Enormous Strike Zone. Bolin had trouble throwing strikes, a problem that was eased considerably when they made the strike zone a whole lot bigger. He took full advantage.

43. In 1947, the majors instituted a rule that stated that any player signed to a large enough contract could not be sent to the minor leagues for two years. Ready or not, they had to go on the major league roster. John Antonelli was one of the first bonus babies - an 18 year old who had received a $50,000 bonus. So a rookie in 1948, Antonelli pitched 4 IP - four - and an awful lot of batting practise. He was used sparingly over the next two seasons as well - and then he did two years of military service. He finally made the Braves rotation in 1953, went 12-12, 3.18 in his first season. But the Braves had three LH starters, and traded him to the Giants for Bobby Thomson in 1954. In that championship year Antonelli went 21-7, 2.30. He continued to pitch well through 1959, winning 20 games in 1956 and 19 in 1959 before he started to scuffle. After brief stops in Cleveland and Milwaukee, he was dealt to the expansion Mets. He was just 31 years old, but he decided to retire. He said he was tired of the travelling, and I'm sure he has no regrets about not being part of a team that lost 120 games.

44. With Cepeda gone, Willie McCovey finally had 1B to himself, and had some stupendous seasons, including an MVP campaign in 1969 before injuries began to grind him down. Despite that, and despite being platooned for years at the beginning of his career, he cleared 500 HRs and coasted into the Hall of Fame. McCovey is the player young Fred McGriff was always compared to, and they did prove quite similar. McCovey's peak seasons are more impressive, but McGriff was much more consistent and durable from year to year. Neither player ever caused a problem. Neither player ever did anything controversial, or even said anything memorable.

45. Slim pickings here, but Tim Worrell probably had the best years of his long, nomadic career working out of the San Francisco bullpen in the early 2000s.

46. Kirk Reuter spent almost ten years in the Giants' rotation, and won 105 games there, befuddling hitters with slop. But Larry Jansen was just a little better, winning 20 games twice, 122 altogether over his nine year run in the New York rotation in the 1950s. And he was the pitcher of record when Thomson hit the big home run. Counts for something!

47. Rod Beck was a modern closer, who came up with the Giants in the early 1990s. But I think Don McMahon, who wrapped up his long career with the Giants at age 44, is more interesting. The great career relievers all emerged in the National League in the 1950s - Lindy McDaniel, Roy Face, Hoyt Wilhelm, McMahon. Major league managers had no idea at the time how much a reliever could pitch, and it would take almost twenty years before they'd begin to figure it out. So relievers would throw 130-140 innings in a season, and in a year or two their arms would fall off. McDaniel, Face, and Wilhelm were the exceptions - but none of them threw very hard. McMahon was the only hard throwing reliever from that era who lasted. How come? He only threw more than 100 IP twice in his long career, and never more than 109.

48. I generally remember Rick Reuschel as the big RH workhorse of the Cubs rotation in the 1970s - eight straight seasons throwing one sinker after another, making at least 35 starts and working 230 IPs. Arm miseries set him back for a while, but he re-emerged with the Pirates in his 30s, and finished up giving the Giants his final five seasons, winning 19 games for them at age 39 and 17 when he was 40.

49. It took a long time for Hoyt Wilhelm to get a chance. He was 29 years old when he finally made it the majors, having fought a war and served a lengthy minor league apprenticeship. As a rookie reliever, he won 15 games and led the NL in ERA, and followed that up with two more seasons almost as impressive. He scuffled a little over the next two years, and was traded to St. Louis in 1957 when the Giants thought they needed a first baseman. Wilhelm, though 34 years old by now, was just getting started. He would soon find his way to the Orioles and the White Sox, where he spent the heart of his career, and he was still pitching effectively in the major leagues in the early 1970s. He made his last major league appearance in July 1972, tossing a pair of shutout innings against the Phillies, two weeks before his 50th birthday. During his time with the Dodgers, Wilhelm passed it forward, teaching his knuckleball to a young reliever named Charlie Hough. About 35 years later, Hough would help a struggling Texas pitcher named R.A. Dickey master the same pitch.

50. The Giants invested a first round pick on a high school pitcher named Scott Garrelts in 1979, and it worked out pretty well It took Garrelts a while to find the strike zone (in his first pro season, he walked 149 in 176 IP - wonder how many pitches it took to do that? He was 18 years old, by the way.) He had some fine years working out of the bullpen, moved to the rotation in 1989 and led the NL in ERA as the Giants went to the World Series. And then... his arm fell off. He threw his last ML pitch in 1991, still only 29 years old.

51. Randy Johnson wound up his Hall of Fame career here, winning his 300th game at age 45, but let's remember another left-hander. The Giants drafted Noah Lowry with the 30th pick in the 2001 draft. He moved into the rotation in 2004, and was coming off a nice 14-8 season when the surgeries began - to his shoulder, his elbow, and even his chest to address an unusual circulatory problem. He never pitched in the major leagues, and can barely use his left arm in everyday life. Pitching can be bad for you.

52. Not much to choose from. Yusmeiro Petit is now with Nationals, but he previously spent several years as a swingman with the Giants. In 2014, he retired 46 consecutive batters over eight relief appearances, breaking Mark Buehrle's record. And then, in the Giants' championship run, Petit picked up a win in the Division Series, the League Championship series, and the World Series.

53. Slim pickings. Jonathan Sanchez spent three years and change in the rotation, pitching a no-hitter and starting a World Series game.

54. This one's pretty easy - it's not like there are a lot of options - as Sergio Romo is now starting his ninth season in the San Francisco bullpen. He's mostly been an effective setup man, but has filled in as the closer when required.

55. I never thought there was anything particularly freakish about Tim Lincecum. You don't have to be 6-6 to throw really hard, evidence provided over and over again in the game's long history. And I never thought his delivery was remotely unusual - he looked just like Orel Hershiser to me. He was selected 10th overall in the June 2006 draft out of the University of Washington, and was starting in the major leagues within a year. He simply blew the National League away - he won the Cy Young in both of his first full seasons, led the NL in Ks three years in a row - and then he lost it. He's been scuffling for four years now, and is an unsigned free agent at this very moment.

Only one man of interest has worn the strange numbers beyond 55, and that would be #75, Barry Zito. He was probably one of the worst free agent signings ever, but in the 2012 post-season the Ghost of Zito Past got up and saved the Giants season, pitching brilliantly against the Cardinals in a potential elimination game, and then beating Justin Verlander to open the World Series.

The Giants can boast of having more Hall of Famers than any other franchise. This is partially because Frank Frisch - himself a deserving Hall of Famer, basically the Roberto Alomar of the 1920s - got many of his old teammates (Fred Lindstrom, Chick Hafey, Dave Bancroft, Ross Youngs, George Kelly, Rube Marquard.) inducted while he was chairing the Hall's Veterans Committee in the early 1970s. This has created all sorts of problems in trying to determine what the Hall's de facto standards are or should be. Some of these men are only remembered in order to make an argument against their Hall-worthiness, which is just sad. George Kelly was a very good ballplayer. If we think of him today, we ought not to be thinking of "This is Exhibit A of guys who don't belong in the Hall of Fame." Somehow, the honour has tarnished his memory.

Let's also mention the 19th century stars - Roger Connor, Buck Ewing, Mickey Welch, John Montgomery Ward, Jim O'Rourke, Amos Rusie. And the great players from McGraw's early teams - Roger Bresnahan, Joe McGinnity.

And, especially, Christy Mathewson. A great, great player - but even more significantly, the game's first true popular idol. He was the first genuine role model for little boys the game would produce. Matty was the game's first hero.

36. When people think of Gaylord Perry, they don't think of the 300 wins or the two Cy Young Awards, or his mind-boggling durability and consistency. They think of the spitball. Which is exactly what Gaylord Perry wanted people to think. Especially hitters. He wanted the idea in the batter's heads. The Perry brothers came out of North Carolina. Jim made the majors first, in 1959, and won 18 games in his second season; Gaylord, three years younger, came up in 1962 and spent two years scuffling, just trying to make the team. He then spent two more years working as a swingman himself. He was 27 years old before he finally went into the rotation full-time. In his first season as a starter he won 21 games and made the All-Star team. He was just getting started. Over a 15 season span, Perry averaged 18 wins and 285 IP, picking up two Cy Youngs awards along the way; never pitching less than 200 IP, and six times more than 300. Unfortunately, in a historically bad trade, the Giants had traded him for the Ghost of Sam McDowell fairly early in this run - he did win 20 games twice for the Giants, but he won his Cy Youngs for Cleveland and San Diego.

37. Candelstick Point may not have been the best place in the world to build a baseball stadium. It was pleasant enough during the day, but in the evenings, fog and damp rolled in from the San Francisco Bay. Along with gusts of wind. Big, powerful gusts of wind. Strong enough to lift the huge cage teams use for batting practice into the air and set it down around second base. Such gusts would surely be strong enough to make a grown man lose his balance, especially if he happened to be standing on one leg at the time. That's what happened to Stu Miller in the first of 1961's two All-Star Games. As there were a couple of men on base, he was called for a balk, of course. If that's Miller is best remembered for it's a shame. Miller was basically the Keith Foulke of the 1960s. His fastball was in the low-to-mid 80s, and he didn't really have a breaking ball. Nevertheless, he pitched for 16 years in the majors, led both leagues in saves (with the Giants in 1961, with the Orioles in 1963). He did it all with that pedestrian fastball and a killer changeup, proving once more the eternal wisdom of Warren Spahn that: "Hitting is timing. Pitching is upsetting timing." The man who had the number before Miller was a LH reliever named Don Liddle, who gave the Giants three pretty good years out of the bullpen. Leo Durocher was probably the first manager who made a point of keeping a dependable southpaw available in his bullpen, and it was Liddle whom Leo called on to face Vic Wertz in the 1954 Series, the score tied and two men on base. Wertz, of course, smashed the ball about 440 feet to dead centre, but it was the Polo Grounds and Willie Mays was there. Durocher came right out to summon a new pitcher. Liddle gave him the ball and said "Well, I got my man."

38. I don't care how well some guy named Brian Wilson pitched for the Giants; the real Brian Wilson is a twisted genius, a man much too fragile for this rough world, but still America's greatest master of melody since Gershwin. So this spot goes to Greg Minton, who teamed up with Gary Lavelle to give the Giants an excellent L-R combo out of the bullpen. Bonus points for one the game's all-time great pickoff moves.

39. Bob Knepper had his best years with the Astros, so let's go with Mike Krukow, a tall RH who had a long career as a mid-rotation starter, never winning more than 13 games until at age 34 he unexpectedly pulled off a 20-9 mark for the 1986 Giants.

40. You all know about Madison Bumgarner. I just think it's wonderful that there exist a player known informally as "Mad Bum." That has to be, like, the Greatest Name Ever.

41. A year after trading Garry Maddox for Willie Montanez, the Giants shipped Montanez to Atlanta to obtain third baseman Darrell Evans. Evans had been drafted by Kansas City, but they'd let him escape to Atlanta in the Rule 5 Draft. Evans was a pretty crude third baseman but luckily for him, one of the greatest third baseman of all time (Ed Mathews) was working for the Braves, and helped Evans develop his skills. Evans had a big year in 1973, hitting 41 HRs - but his overall skills weren't the kind that were obvious to the baseball world at the time. He had power, but outside his one big season, he generally hit about 20-25 HRs; he did not hit for average, generally in the .240-.250 area. He was a very good third baseman, but he didn't dazzle you with his glove. He regularly drew 90+ walks a year, but it was the 1970s and most people just didn't notice. Evans was happy to return to California (he''s from Pasadena) but seeing as how the Giants already had the immortal Ken Reitz at third, he played first base when he arrived. That winter, they traded for Bill Madlock, and Evans moved to the outfield. But late in 1977, the Giants moved Madlock to second base and installed Evans at third, where he stamped out interchangeable seasons through 1982 while providing fine defense at third. He was moved to first base in 1983, and slugged 30 HRs in his final season as a Giant - he then joined the Tigers as a free agent, where he finally got to play in a World Series.