This was a noteworthy achievement indeed, for all the wrong reasons. Since 1900, only 11 teams have surrendered more than 1000 runs in a season. Six of those teams had the ill fortune to play during the Great Golden Age of Hitting (the 1930s, of course.) Just two staffs have surrendered that many runs in the last 70 years - the 1996 Tigers and the 1999 Rockies.

But the 1911 Boston Rustlers, the first of that sorry crew, were active before the great offensive explosion of the 1930s (and the lesser one of the 1990s.) This was long before the home run had become a central factor in the offensive game. Boston gave up their runs the old-fashioned way - by sheer ineptitude, and lots of it.

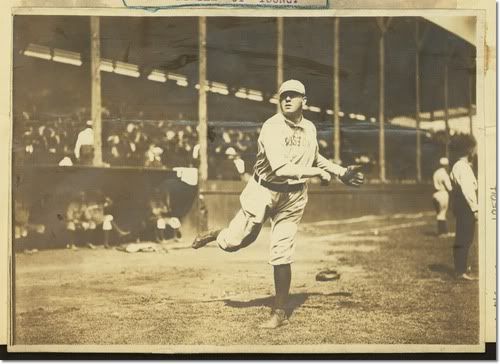

The staff was so bad that they had acquired Cleveland's ancient Cy Young in August. Young had turned 44 before the season began, and the big man had grown too portly to have much hope of fielding his position effectively. This was a significant problem back in 1911, when teams were in the habit of bunting as many as five or six times a game, sometimes more. That shortcoming notwithstanding, after a disastrous Boston debut (3 IP, 9 H, 8R) that Young was lucky to escape with a no decision - old Cy had quickly settled in as the best pitcher on the staff. That's not saying much, of course, but even so Young went 3-1, 1.50 over his next four starts, one of them a five-hit shutout of these same Pirates.

After that promising beginning, the old man had faltered. He was driven from the box in his next two starts, losing one of them and allowing 12 runs in just 8.2 innings.

But this Friday in Pittsburgh, matched up against Pirate ace Babe Adams (the 1909 WS hero, who would go 22-12, 2.33 in 1911) the old master was in the house, and he was able to turn back the clock one more time. The Rustlers squeezed out one run on a seventh inning single by Al Bridwell and it was all Young would need. He wasn't quite the man who had thrown baseball's very first perfect game, but he was quite good enough. He scattered nine hits on the day, didn't walk anyone, and retired pinch-hitter Tommy Leach with two out in the ninth to finish off the 76th shutout of his career.

Young's shutout against Pittsburgh that Friday afternoon 100 years ago brought his season record to 7-6 (4-2 with Boston.) It was the 511th win of his career. It would turn out to be the last. Three days later, he lost his next start 6-5 to the Cubs, giving up the winning run with one out in the ninth; five days after that the Reds beat him 4-1 in Cincinnati. This would be the 749th (we think!) and definitely the final complete game of his career. There's another record that looks pretty safe.

Finally, on October 6, Young took the mound for the second game of a double-header in Brooklyn. Through six innings, the score was tied at three. Then in the seventh, something went terribly wrong. Young retired the first batter. He then gave up a triple to Miller, an RBI single to Wheat (4-3 Brooklyn), a single to Northen, a two-run single to Daubert (6-3 Brooklyn), an RBI single to Daley (7-3 Brooklyn), and three straight RBI doubles to Hummel, Tooley, and Coulson. With Brooklyn now leading 10-3, Weaver relieved Young and allowed the eighth run of the inning to score.

That was Cy Young's last appearance in the majors. It would have been nice for a player so great to have had a more fitting swan song. Ah well - if things didn't end badly, they wouldn't end at all. Young would go to camp with the Red Sox in 1912. He even suited up for some games, and warmed up on the side occasionally. But he never felt capable of actually being able to pitch and in August he made his retirement official.

Half of his life was still ahead of him.

On the one hand, it is obvious that so long as people care about baseball, Cy Young will never be forgotten. The annual award, the unreachable records make sure of that. But even so, he isn't really remembered. Not really. It's extremely unlikely, of course, that there's anyone still alive who saw him play. But he seems to have left very little behind, save those astounding numbers. He wasn't colourful, like Waddell. He wasn't articulate and modern, like Mathewson. He was an old-fashioned figure in his own day. He never played for a New York team, which in terms of public recognition was even more important in those days than it is now. The game didn't really start taking an interest in its own history until the 1930s (when the first generation of players was beginning to die off), with the advent of the Hall of Fame, the All-Star Game, and some serious attention being paid to the game's landmark achievements. Young was already in his 70s by then.

He was a farm boy from Tuscarawas County, Ohio. He was born in a tiny place called Gilmore, and lived most of his life in an even tinier one called Peoli. These were, and remain, rural communities in Washington Township (the population of the township is less than a thousand people.) Peoli consists of about ten houses, a church, and the cemetery where Young himself now lies. It's mostly Amish country now, and Young would not be out of place there today. He was a reserved and decent man in a game populated largely by ruffians. The virtues of country folk were his virtues - he was simple and pious (he refused to play on the Sabbath in the early years of his career), he was hard-working and honest (so much so that he was occasionally pressed into service as an umpire if he didn't happen to be pitching that day). He was not inclined to talk much about anything in general, and himself in particular.

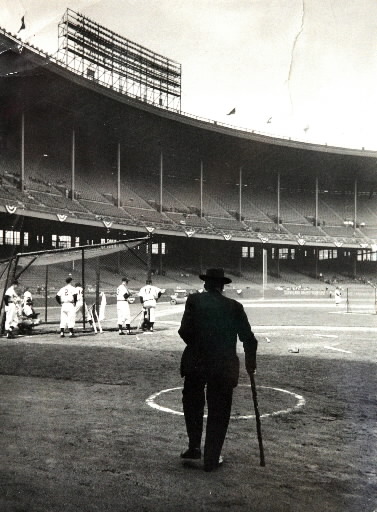

He was known as Dent Young or Farmboy Young before acquiring, at the very beginning of his career, the nickname that has now clung to him for more than a century. He'd left school after the sixth grade to work on the family farm near Peoli, and when baseball ended for him in 1912, he went back to the farm. In later life, after the death of his wife in 1933, he found himself unwilling to live on his farm anymore. He had also suffered some financial reversals - he may have been too willing to assist other old ballplayers - and so in 1935 he began living with his friends and neighbours John and Ruth Benedum. He happily did outdoor work on their farm; he enjoyed chopping wood, and he also believed the work kept him hale and hearty (he was almost 80 years old by this time.) He was always willing to turn up for baseball-related events, and in Reed Browning's remarkable biography (Cy Young: A Baseball Life), there's a photograph of an 87 year old Young, leaning on a cane at Cleveland's old Municipal Stadium watching batting practice in April 1954. The Korean War had ended the year before. The American's League first African-American, Larry Doby, was playing centre field for the Indians. They were taking BP in a huge modern steel stadium that seated 73,000 people. And there was Cy Young himself, born just after the Civil War had ended, who began his career in flimsy wooden ballparks that burned down with regularity, now nearing the end of his days, looking out over that baseball field.

(That's the photograph; it's the reason I've re-posted this story on its third anniversary. I saw it in the Browning biography and I must have stared at it for half an hour. I found it absolutely haunting. It utterly mesmerized me, I couldn't stop looking at it, and thinking about it. Cy Young! In the flesh. And all those players, standing around the batting cage... did they have any idea who was standing in their midst? Cy Young, old-time pitcher. Did they know who he was? Who he really was? But I couldn't find the picture on-line when I wrote this piece three years ago....)

Young was a survivor of one of the last great changes in the game. When the pitcher's mound was moved back to 60 feet, some of the best pitchers around - Bill Hutchinson, George Haddock - lost much of their effectiveness. Young and Kid Nichols - Young a big man, Nichols much smaller, but both young men and hard throwers - were the pitchers who made the transition with the least difficulty. Both would discover that they couldn't pitch quite as many innings at the new distance, and Young found it necessary to perfect a changeup to ease the strain on his arm, but otherwise they carried on just as they had when they were throwing from 50 feet.

Young's records look freakish and unbelievable, but there was nothing freakish about him. He wasn't the greatest pitcher who ever lived. He was seldom the greatest pitcher in the game at any given moment. Nothing Young did in any one season was beyond the reach of any of the other great pitchers in the game at the time. He won more games than any pitcher who ever lived, but he only led his league in wins five times. He pitched more innings, he started and completed more games than any pitcher in history - but he only led his league in games started once, innings pitched twice, and complete games three times. There was usually some other pitcher around who was a bit better than Young at a particular moment. There was Kid Nichols and Amos Rusie in the 1890s, there was Rube Waddell and Christy Mathewson after that. What made Young special, if not unique, was his longevity, his ability to maintain the same high level of performance over two whole decades. His three best seasons came at ages 25, 34, and 41. There have been modern pitchers just like this. Young was to his time what Warren Spahn or Don Sutton were to theirs. Not quite the very best pitcher around, but always one of the best.

He lived off his fastball and his control - there were certainly others who threw harder, but Young was always a power pitcher (the famous nickname came from the condition of a wooden fence he used to warm up against - an observer said it looked as if it had been hit by a cyclone.) And he gave nothing away. He was by far the best control pitcher of his time. What would he have been had he been born 100 years later, in 1967? I assume he would have been exactly what he was in his own time. All the advances, in training and nutrition and coaching, that have made modern players so much better would also have made him better, bigger, and stronger. If he had been born in 1967, I assume he would have been an outstanding pitcher for close on 20 years, and quite likely won 300 games or so. The changes in the game ensure that his numbers would look drastically different - in his career, Cy Young gave up the same number of home runs as Eddie Guardado - but a great player is a great player. He would have started and won fewer games, struck out more batters, allowed more home runs... but the same man, moved to this place on the space-time continuum, would have been what he was.

So let me just say this about him: he was a real man, a real player. He really did those things - pitched all those innings, won all those games. Lived a life, had a career. We can't really remember him, of course. None of us were there. We can just try to see what he was a little better...