I've got an idea! Let's create a pitcher!

And let's make him a monster. A dragon...

For his best pitch, let's give him... let's see, let's see. I know. Let's give him the best pitch ever. We actually had a poll a couple of years back on this very subject: the toughest Hall of Fame pitch to hit in major league history. The Bauxite consensus agreed with Jim Thome and voted for Mariano Rivera's cutter. So let's give our man something like Mariano Rivera's cutter, a fastball that zips

through the strike zone with a unique, upward-moving right-to-left sail that snatched it away from a right-handed batter or caused it to jump up and in at a left-handed swinger - a natural break of six to eight inches - and hitters who didn't miss the ball altogether usually fouled it off or nudged it harmlessly into the air. The pitch, which was delivered with a driving, downward flick of... forefinger and middle finger (what pitchers call "cutting the ball") very much resembled an inhumanly fast slider...

Our man will have absolute command and control of this fearsome pitch, which he will also throw as hard as anyone in the game throws a fastball.

But we need more than this, surely. That cutter will take Mariano to the Hall of Fame, but we can't get through a whole game with just one pitch, can we? Mariano never tries to get through more than two innings. Our man has his sights set on much larger chunks of the ball game. And so he needs a breaking ball of some kind.

Let's give him a slider, and let's make it a honey: a Dave Stieb - Francisco Rodriguez type of slider, a

superior breaking ball that arrived, disconcertingly, at about three quarters the speed of the fastball and, most of the time, with exquisite control.

You're going to miss more than a few bats with that combination. But you don't always want to miss the bat, and on those occasions, it would be nice if you had a second fastball; it would be truly excellent if, like Roy Halladay, you could complement your cutter with a world-class sinker:

a fastball that broke downward instead of up and away; for this pitch, he held the ball with his fingers parallel to the seams (instead of across the seams...), and he twisted his wrist counterclockwise as he threw - "turning it over," in mound parlance.

Because there are times when you want the hitter to put the ball in play, as our hero once tried to explain to his bewildered third-baseman:

"I always told him I didn't give a damn where he played unless there was a right-handed batter coming up with a man on first and less than two out, but then he should be ready, because he'd be getting a ground ball... And I'd throw a sinker down and in, and the batter would hit it on the ground to Mike to start the double play, and when we came in off the field Mike would look at me with his mouth open, and he'd say, "But how did you know?" He didn't have the faintest idea that when I threw that pitch to the batter he had to hit it there."

Anything else? Oh, let's make him a superior athlete. What the hell. Good enough at another sport to go to college on a scholarship, good enough to win nine consecutive Gold Gloves...

And one thing more: let's make him insanely, ferociously competitive. As driven by the need to win and the need to succeed as Michael Jordan ever was. In fact, all the rest of this somewhat mind-boggling arsenal notwithstanding, if there is one single trait that most distinguishes this particular hurler, the one thing that people most remember about him, it will be this: his ferocity as a competitor. It will be legendary.

Considering everything else he's got working for him, it will have to be legendary. Naturally, such a pitcher will probably have a somewhat aggressive approach to the hitter, and a desire to establish who's in charge:

"I don't like batters taking that big cut, with their hats falling off and their buttons popping and every goddam thing like that. It doesn't show any respect for the pitcher. That batter's not doing any thinking up there, so I'm going to make him think. The next time, he won't look so fancy out there. He'll be a better looking hitter."

It would surely take some Dr Frankenstein to build such a monster, and I suppose there may be some young 'uns who think this old fool has forgotten his meds and is telling mythic tales of some Paul Bunyan like figure from some undocumented and impossible to verify Land Far Away in Ages Long Past.

But no. I'm telling you now: this ain't no Sidd Fitch fiction. There really was such a pitcher. He had Mariano's cutter, and K-Rod's slider, and Doc's sinker. He fielded his position like a cross between Greg Maddux and Kobe Bryant. He threw strikes - at his peak, he walked fewer than two batters per 9 IP. He was an utterly possessed and driven competitor.

Forty years ago this coming Monday, he threw a shutout against the Mets. It was his second start since the All Star Break (he had been named to the team, but didn't get in the game.) He struck out 13 and didn't walk anyone. He scattered seven singles - one runner made it to second base, one made it all the way to third. The complete game victory improved his record to 13-5, and lowered his ERA to 1.01 (yes, 1.01). It was his tenth complete game victory in a row, seven of them by shutout - and he would throw yet another shutout just four days later, blanking the Phillies on six hits, and yet another CG victory five days after that (trailing 6-0, the Mets would scratch out a single run).

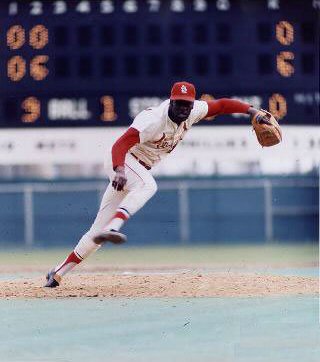

So yeah. Meet this impossible creation. Meet him in the middle of America's annus horribilis, the year that began with the Tet offensive, proceeded through the murders of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, descended to the chaos in the streets of Chicago during the Democaratic convention, and concluded with the election of Richard Milhous Nixon as President. In the middle of that dreadul year, in June and July of 1968, Bob Gibson - for who else could it possibly be, and all of these quotes are from "Distance," Roger Angell's marvellous 1980 portrait of Gibson for The New Yorker - would go 12-0, with an ERA of 0.50, with 91 Ks and 16 BB in 108 IP. He made 12 starts, completed them all, and threw 8 shutouts. Fully half of the six runs he would allow would come in the very first game of the twelve, a 6-3 victory over the Mets, in which he gave up the only home run he surrendered during this two month reign of terror. In the other 11 games, he gave up a single run three times and no runs whatsoever eight times.

It's not always that easy to find a closer who can do that for 11 games, working just one inning each time. Do the math - if your closer allows a single run three times and shuts down the opposition the other eight times - he's given you a 2.45 ERA over the 11 games, and you're probably reasonably pleased.

So let's run those numbers. This really happened:

G GS CG SHO IP H BFP HR R ER BB IB SO WP HBP BK 2B 3B GDP ROE W L ERA

12 12 12 8 108 63 398 1 6 6 16 0 91 1 4 0 9 0 9 3 12 0 0.50

https://www.battersbox.ca/article.php?story=20080715021654488